Artist Blends the Material with the Digital

|

|

|

He is a true man of the ‘Sixties, though he didn’t discover the era until the early ‘Eighties. And oh yes, he was born in 1970, the year the Beatles broke up.

And it was discovering the Beatles during a BBC film fest when he was ten that turned Michael Gillette into a time traveler in the first place.

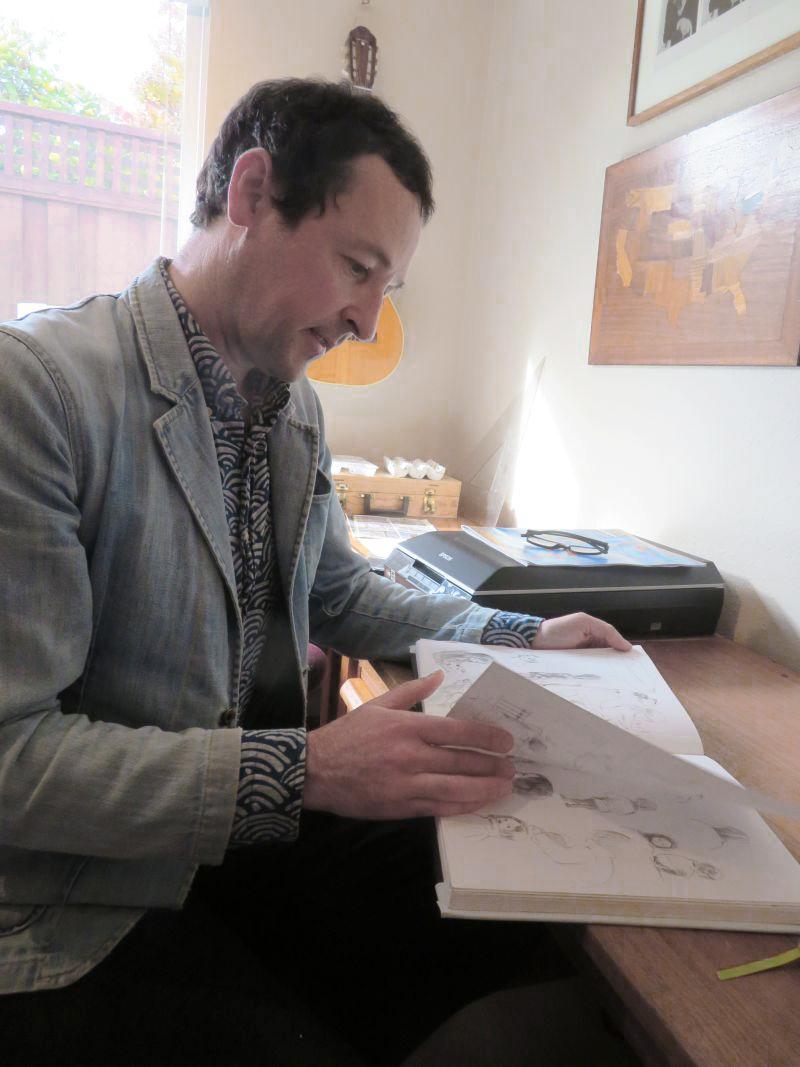

Gillette, who lives with wife, Cindy, and daughters, Eleanor and Josephine, in an Eichler home in Marin’s Lucas Valley, has been a commercial illustrator for decades. He works in his home studio.

His work is deliberately varied; there is no signature Gillette look but, he says, “I’ve always enjoyed the mid-century aesthetic and it’s inspired much of my work.”

In fact, a new series of paintings – destined eventually for art gallery walls and, perhaps, walls in your home – was inspired directly by his Eichler.

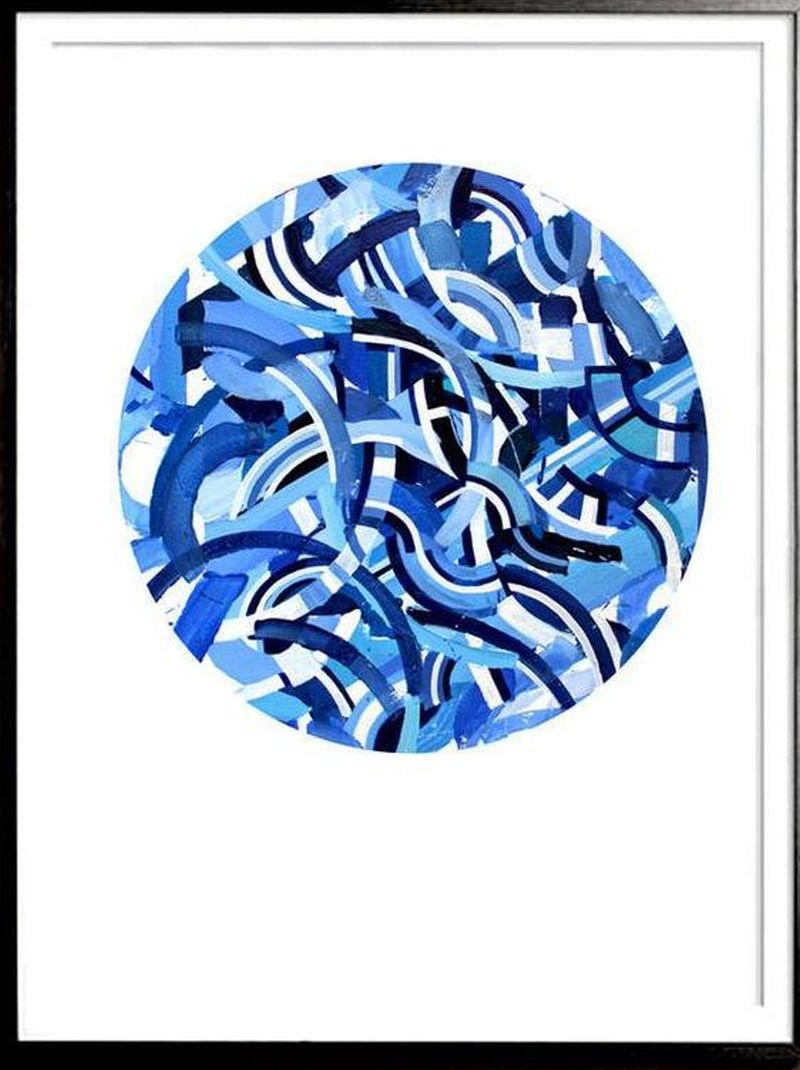

“I wanted to think of work that would fit in the house, that would be different for me,” he says of the small colored works of swirling, interlocking ribbon-like forms, that are a work in progress.

They are his first abstract works.

|

|

|

“I thought of making abstract work but never got around to it. But in the last couple of months I started experimenting around and started making stuff, and it’s really great.”

“It’s the influence of the house,” he says.

“Because it’s such a clean and modern format,” Gillette says of the Eichler home, “there are certain kinds of art that really sing in it, and it is of the mid-century era to have the abstractions of the ‘60s. I mean pop and abstract work just fits so perfectly here.”

He enjoys working both as a commercial and fine artist, as he appreciates variety throughout his work.

Gillette, who grew up in Great Britain, with parents who were artists and teachers, enjoys commercial art in part because each job challenges the artist to do something new.

“Commercial work has pushed me in directions I otherwise would never have gone, and allowed me to continue moving,” he says. “I enjoy having a brief to respond to.”

From the start of his career, Gillette has blended 1960s art and 1960s music. Aiming for a music career, he played bass with a rock band but decided his talents lay elsewhere. Soon he was designing art for bands that were part of the scene.

|

|

|

He fell in love not just with the Beatles but with another icon of the ‘60s, San Francisco psychedelic poster art, starting with a book by artist Rick Griffin his mum bought for him when he was 13.

“That’s why I came on holiday [to San Francisco[,” he says. “And then when I came, it instantly felt familiar and it also felt...I had never gone anywhere [before] that said, ‘You’ve got to move here.”

Gillette moved to the city in 2001. The family moved to Marin from the City's Bernal Heights about a year ago as their kids needed more room, he says.

Music has remained a major part of Gillette’s commercial work. He is about to start a series of celebrity portraits for a cookbook by musician Questlove (known for fronting Jimmy Fallon’s band).

“Music, it’s always where I’ve drawn the most energy from,” Gillette says.

“Over the years, I’ve worked with many amazing people, from Beck and the Beastie Boys, to campaigns for Levi’s,” Gillette says, “and an ongoing relationship with the Ian Fleming estate and all things [James] Bond!” For several years he drew for New Yorker magazine.

Gillette explains why he varies the look of his work: “I didn’t want to solve different problems with the same visual solution,” he says. “A groove becomes a rut quite quickly,” he adds.

Freelance artists cannot fall into ruts and remain in business, Gillette says, emphasizing the need to keep up with a changing market and technologies. Magazines, records, and other hard-copy items that were originally his stock in trade have fallen away as digital has taken over.

|

|

|

In the old days, Gillette would cart his art to the offices of publishers and the homes of musicians. Today he shares material online.

Digital has its plusses and minuses. It has allowed him to work from home for distant clients. “I’ve been very lucky to see the kids growing up at close quarters. I’ve made a lot of work with a child on my head, hugging my head,” Gillette says with a laugh.

“When I worked for the New Yorker I worked for someone called Chris, and for a year and half I was convinced she was a man. When I found that out, that’s really not cool, that’s not good. You’re missing out on the human condition. It’s a massive change that you’re no longer face-to-face with the people you are working for.”

Today, Gillette says, he makes a point of talking to his all his clients to establish a human touch.

Gillette also sees the value of creating with pen and brush versus on a computer. He teaches digital illustration at California College of the Arts and knows that some of his students will never handle a paint brush. And why should they? Digital paint brushes create work that can be indistinguishable from the real thing – and in much less time, he says.

“I’m not a Luddite, but I do understand that there is a soul to making art that can be missed in the world of making digital art,” he says.

“It’s a therapeutic thing to make physical art, and it’s not such a therapeutic thing to make digital art,” he says. “Well, for me. Some people might find it that way. But it’s the tactile nature of materials, and the slowing down of how we deal with our lives, how we process our life, to make physical work.”

“I see the benefits of one side, and I see the soulfulness of the other,” Gillette says, adding, “It’s a digital world.”

|

|

|

- ‹ previous

- 47 of 677

- next ›