Focusing on the Artistic Side of Eichler Homes

|

|

|

In the world of merchant builders, as housing developers were called during the mid-20th century, Joe Eichler stands out for several reasons, including his fanatical determination to build nothing but truly modern homes and his willingness to sell to people of all races.

Here’s another: the at-times gruff, cigar-smoking Joe was likely the only such builder to spend money to send his employees to art classes.

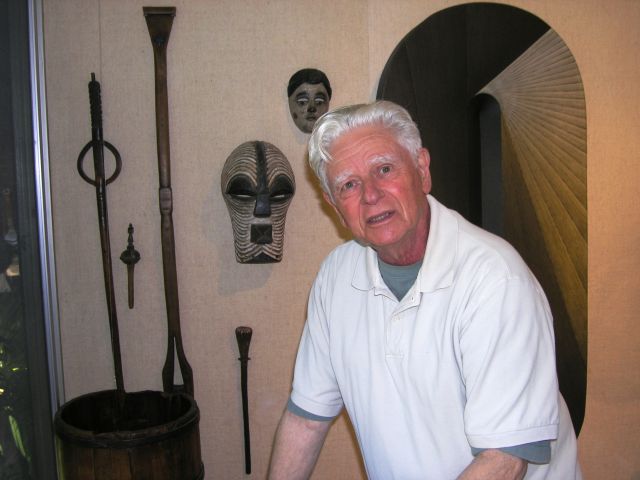

Frank LaHorgue, who started working for Eichler Homes in 1961, recalls that he had no background whatsoever in art when he attended the first of the evening classes Eichler ran for several years.

“I didn’t have any art knowledge until I got involved with Eichler,” LaHorgue says, adding that he and his wife went on to buy and collect art. LaHorgue worked for Eichler until 1965, in sales among other roles.

He recalls the evening sessions as enjoyable as well as illuminating, and notes that they were not mandatory for staff. But they were well attended.

|

|

|

“It was all part of Eichler’s concept of building a team, building something that was productive,” LaHorgue says. “He saw that the relation of art to architecture was an important connection. Certainly it was important for the salesmen to have an understanding of that.”

Attending the classes were salespeople and office staff. LaHorgue doesn’t recall any of the construction workers attending. Nor did Joe himself attend any of the classes that LaHorgue went to.

Jim Dougherty, who also worked for Eichler during this period, says of the sessions, “It was more of a college education type of thing.” Dougherty adds, “He just wanted to show the philosophy of what he was doing.”

Dougherty thinks Ned Eichler, Joe’s son and at times head of marketing, played a role in running the sessions.

The professor was Matt Kahn, whose day job really was as a professor – at nearby Stanford University, no less. Kahn (1928-2013) became a legendary figure on the campus for his creative methods of teaching and his personality.

Weaver Lyda Kahn, Matt’s wife, took part in some sessions, and so did artist Gordon Brofft and his wife, Bonnie Brofft. The Broffts also worked on interiors for Eichler model homes. Sessions, held in the Eichler Homes offices, consisted of slide shows and lively discussions.

Kahn started teaching at Stanford in 1949 – without a college degree. He became a full professor in 1965 and won the Dean's Award for Distinguished Teaching in 1992.

Kahn taught design, painting, drawing, sculpture, and color theory for more than 60 years. He lived in a custom Eichler on the Stanford campus and decorated it every Halloween with pumpkins carved – as an assignment, of course – by his students.

Kahn and Lyda began designing interiors for Eichler model homes in 1954. One model they worked on was published in Life magazine in November 1954 as ‘Art About the House.’

Artists such as Ernie Kim, Anne Knorr, Bryan Wilson, the Kahns, and others contributed artwork to show how art could be integrated into a middle-class home.

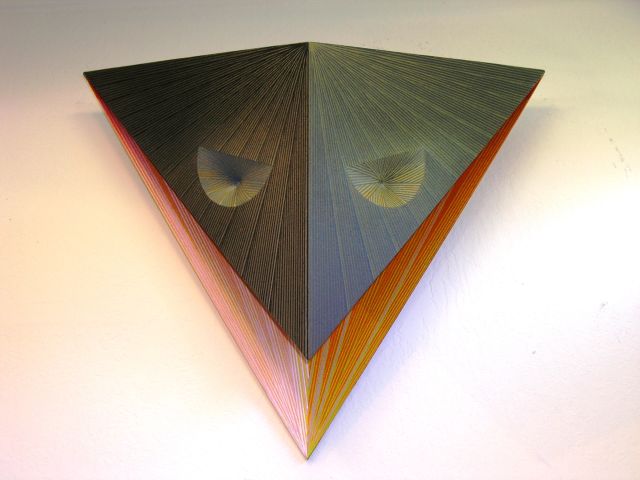

Matt always insisted that Eichler homes were ideal places to display art because they were “permissive.” You could successfully display any sort of art, not just art that “fit” the architecture. That was a suggestion that repelled him.

|

|

|

“My take on Eichler homes is a little bit different than other people’s,” Kahn said in a 2007 interview. “I’m not interested in its relationships to Frank Lloyd Wright. In fact, almost the opposite.

“Frank Lloyd Wright’s work tended not to be permissive. Eichler homes, by virtue of the fact that there were many of them and they were systematically built, are insistently permissive. You must in an Eichler home expand and express yourself. And that was very much the draw for me and my wife.”

The Kahns came to work for Eichler, he said, when Joe and one of his architects, Frederick Emmons, “were upset that they couldn’t seem to get a model interior done in the spirit of the house. The local [furniture] dealers obviously wanted to push the things they wanted to sell. They were very often out of the spirit and out of scale.”

Matt and Lyda made a quick fix to one model – borrowing from the Stanford chemistry department “big glass flasks and filling them with colored water and setting them around on floating cabinets in the kitchen, and doing little things that would give a younger spirit or original spirit to the interiors.”

|

|

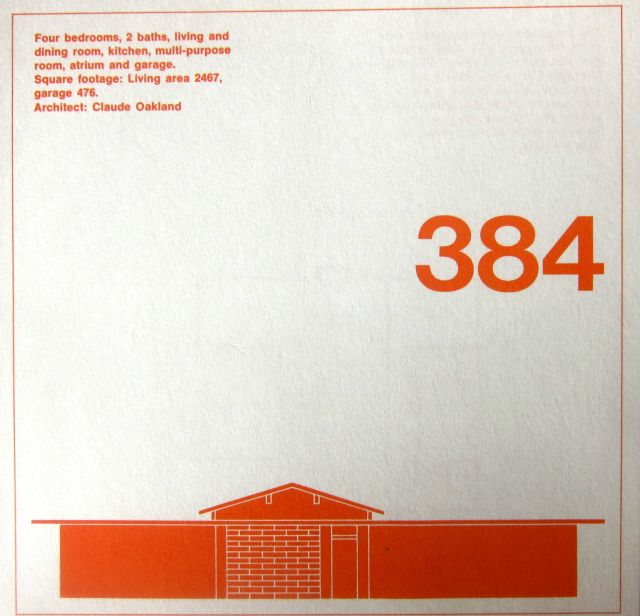

The brochure for Grandmeadow, an Eichler development in Mountain View, gloried in bold typography.

|

“Joe Eichler and Emmons were very excited about it, very pleased. And from that I think probably came the first suggestion that maybe we should try our hands at furnishing a model.”

Matt Kahn got along well with Joe Eichler, though he recalled they sometimes butted heads.

“Neither Joe nor I were very good at concealing feelings, and we didn’t always agree,” Kahn said.

Eichler would look over the model interiors before opening them to the public, Kahn said. “If Joe liked something, he’d say very little or be smiling. If he didn’t like it, he would be specific.”

“Very frequently,” Kahn said, “when we did a model, there would be an example of my work and my wife’s as part of the installation – my paintings, or a piece of furniture, something I would be responsible for.”

- ‹ previous

- 258 of 677

- next ›