Legendary Design Lectures Still Enthrall

|

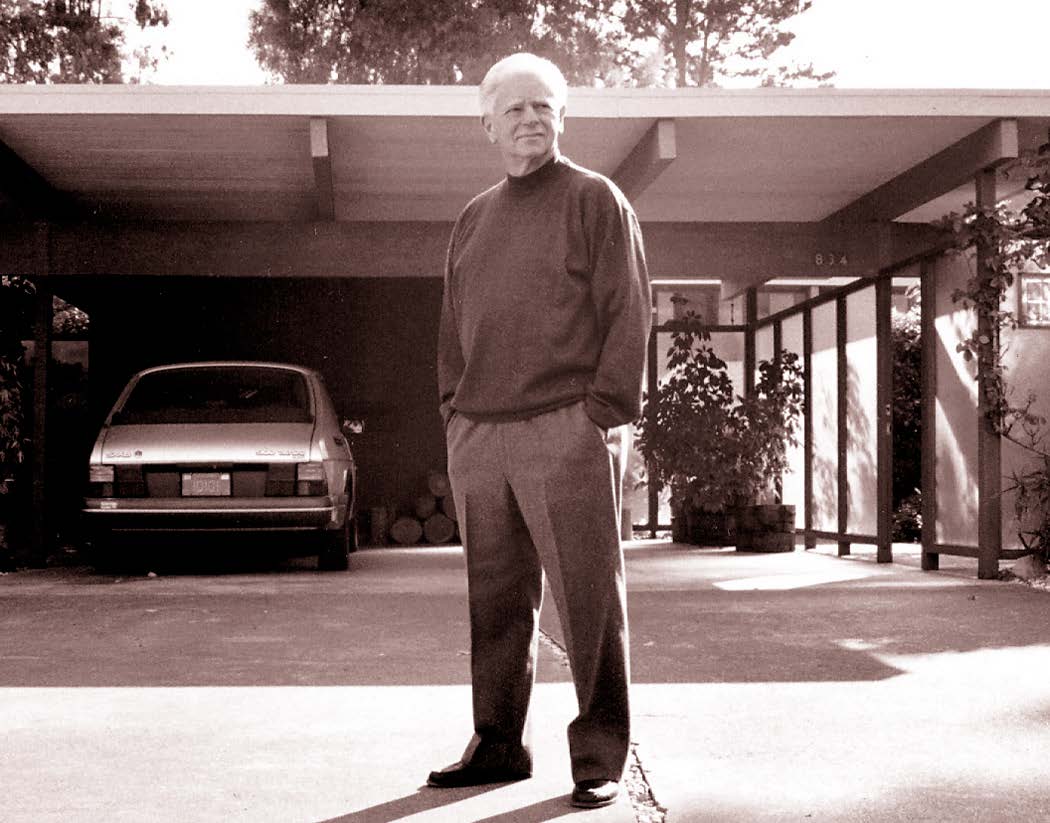

When developer Joe Eichler needed an artist, his go-to guy was Matt Kahn. Kahn and his wife, Lydia, furnished many Eichler model homes. Kahn created art for some of them, including the steel X-100 of the San Mateo Highlands.

And when Joe wanted his sales staff and other employees to learn something about art – how many homebuilders would have dreamed about doing this? – naturally Joe called upon Kahn (1928-2013), who worked for Eichler Homes from 1954 into the early 1960s.

Any number of Joe’s crew knew Matt, of course, so they probably guessed he wouldn’t start with the cave drawings of Lascaux and proceed chronologically through Reims, Bernini, and Delacroix to Jackson Pollock.

And we don’t really know what Kahn did teach them during these early 1960s classes. But a good guess is he drew from a curriculum that evolved during his 60-plus years as a design professor at Stanford, Art 160. The 'Design: Soul and Body' lectures became legendary, open not just to the undergraduates in the class but to the campus as a whole.

|

“They were extremely inspiring,” recalls designer Peter MacDonald, who lives in a Palo Alto Eichler. “As soon as you left the room you wanted to go design something.”

Thanks to Claire and Ira Kahn, Matt’s children, and to Stanford, six of Kahn’s lengthy but enthralling lectures recorded in 2004 by fans to ensure their preservation are online, for at least a time. They reveal a man passionate about many things and one who saw beauty – well, maybe not everywhere, but in places unexpected.

“Moffett Field on the left,” he says of one pair of slides, “a liquid nitrogen plant on the right. Isn’t it beautiful?”

“I tend to be very emotional about color,” Kahn says, over images of a lime-green Chrysler Imperial and a hot rod painted with flames. “I run around with my camera, and when color is screaming at me, I scream back.” Too many students, he mourns, are “color ignorant, color frightened.”

|

Kahn’s format was simple – two slide projectors filled with slides mostly of his own taking, allowing him to compare and contrast – anything. A flower growing as high on Matterhorn as Kahn could climb that morning, paired with a flower on the Nevada desert floor.

At another point he shows a chrysanthemum flower, comparing it to a football field filled with fans. Another flower, petals open and stamens a-shiver, attract a bee. The flower is an opera house, the bee both singer and audience.

“Nature [is a] fundamental stimulus for design and substance for design,” he says, but adds later, “Nature isn’t always pretty,” over the image of a rather menacing stone.

But sometimes it is more than pretty. Over an image of sea grasses, Kahn observes: “What they’re really doing is making love. This is a pollination moment. How would we look if we needed the assist of a cool sea breeze to make love?”

|

The lectures are dotted with the epigrams for which Kahn was famous – so much so that his students, many of whom have become successful designers, share them.

“If you don’t take risks you don’t get gifts,” Kahn says at one point, and at another, “Nature makes mistakes. But mistakes can be gifts in disguise.”

With students, “He could be sharp with his tongue, but it was never mean-spirited,” MacDonald says.

Kahn had little patience for engineering students who said that art was where they found creative outlet, not engineering. “Engineering is a vehicle for some of the most emotionally audacious and thrillingly inventive images that man has ever made,” he says over images of works by Buckminster Fuller, Frei Otto, and Pier Luigi Nervi.

Kahn was a dedicated modernist but did not admire all of it. Over an image of minimalist glass office towers he says, “You have to pinch yourself to be aware that there are human beings alive inside these spaces.”

|

Yet minimalist buildings could be beautiful and more truly classical in meaning and tone than those embellished with hokey Corinthian columns. “Can you essentialize?” he asks his students. “You will hear me say this again and again and again. Can you beat tradition at its own game?”

Kahn would wake early wherever he was to get morning light, and often stay up late for night shots. Fog in Siena provides a “quality of mystery, ghostliness.” Street lamps along a bridge in Florence appear to be glowing with electricity but have yet to be turned on. “The lamp posts have trapped the light of the setting sun,” Matt observes.

“Light, light, light, light!” he says later.

He shows us the Palazzo Ducale in Venice where the Gothic quatrefoils sculpt morning and evening light, creating beautiful patterns and glows. He then challenges his students:

“Imagine thinking about something like that when you design! Or are you too practical and serious and mature for that?”

The contents of Matt Kahn's Lectures may not be used commercially or otherwise reproduced, in part or whole, without expressed written permission from the Matt Kahn Living Trust. All such inquiries may be addressed to: Ira Kahn, PO Box 411346, San Francisco, CA 94141. [email protected]

- ‹ previous

- 373 of 677

- next ›