Was Eichler a High Rise Builder at Heart?

|

|

|

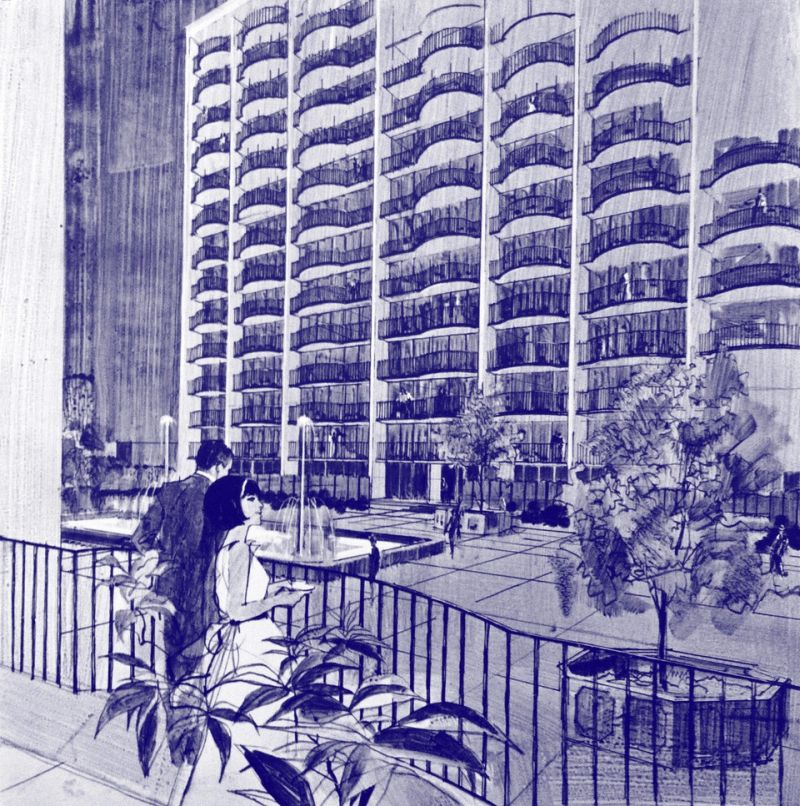

They are the biggest Eichlers of all yet the least known, the high-rise towers built by Joe Eichler and some of his mid-rise townhouse ventures. And some people who love Eichler homes and admire their creator don’t consider them to be real Eichlers at all.

Eichler, after all, won his fame and made his fortune building discrete, largely glass-walled single-family homes on individual fenced lots. As Dee Tolles, Joe’s friend and financier has said, “There’s no Eichlerism in a great, big tall building.”

But what if there is?

What if Joe Eichler’s venture into high-rise and mid-rise apartments, condos and co-ops that began in the late 1950s was no aberration, as some people believe, but a brave, idealistic, and forward-thinking move to keep Eichler Homes relevant as the market shifted from single-family homes for all to a range of housing types to accommodate singles, older folks down-sizing, folks who prefer the excitement of city living, and people who simply don’t want to mow their own lawn?

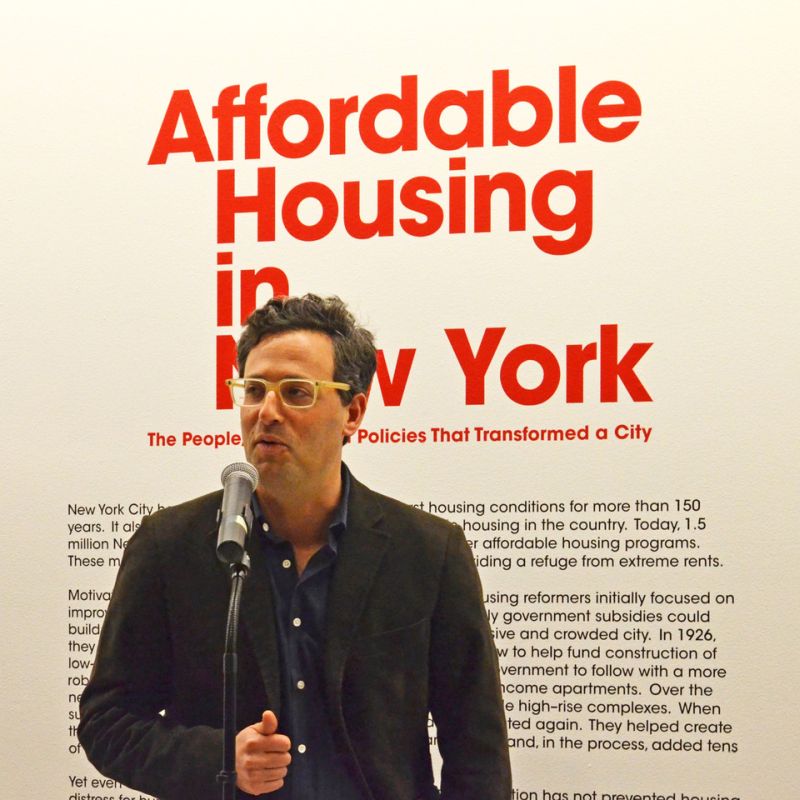

That’s one of the arguments you’ll hear from Matthew Gordon Lasner, an associate professor at New York’s Hunter College, who “studies the history and theory of the U.S. built environment, with particular focus on housing, and the relationship between housing patterns and urban and suburban form.” He is also author of the lively book, ‘High Life: Condo Living in the Suburban Century.’

|

|

|

Lasner also argues that even though many of Eichler's urban ventures failed, and led to Eichler Homes bankruptcy, by addressing the social issues around housing Eichler emerged as an important model for other builders nationwide.

“His experiments were influential nationally,” Lasner says. “They helped other developers across the country see what would work and what might not.”

Lasner is giving his talk, 'Eichler Homes and the Reinvention of Affordable Housings in the Bay Area,' 7 p.m. Tuesday October 10 at Wurster Hall, UC Berkeley. Sponsor is the Environmental Design Archives, where Lasner did much of his research. A donation of $5 is suggested.

Lasner, studying the archives of Eichler’s architects Claude Oakland and Kinji Imada at Berkeley, and A. Quincy Jones at UCLA, is focusing in his talk on 22 of Eichler’s multi-family projects, some built, others not.

He argues that Eichler was motivated in large part by social concerns. That is a view that Ned Eichler, Joe’s son who worked in the business, had also emphasized. It’s important to realize, as Lasner points out, that Eichler’s luxury Summit high-rise atop Russian Hill was atypical of his urban ventures.

|

|

|

Most of Joe’s urban towers, and some of his mid-rises too, were private-public partnerships aimed at alleviating urban ills or attracting people back to cities. Consider Central Towers, a paired high-rise aimed at young professionals that Eichler built in the gritty heart of San Francisco’s Tenderloin.

“Middle-class people were leaving the city center and going to suburbia,” Lasner says. “He thought he could make some of these projects succeed in the Tenderloin.”

Central Towers did not succeed.

Another of Eichler’s San Francisco projects, Geneva Towers in Visitacion Valley, grew so blighted it was imploded in 1998. Other urban neighborhoods, like the tower and Laguna Eichler mid-rises on Cathedral Hill, remain vital communities.

“Eichler was also building mid-rise. He played a big role in popularizing townhouse complexes,” Lasner says.

In his early days, Lasner says, Eichler’s goal involved “the quality of the ordinary American home. He wanted to elevate that quality.”

“In the late 1940s and early ‘50s, cities were wrestling with a different set of large questions,” Lasner says. “By the late ‘50s there were concerns about sprawl, about the high cost of suburban land, and there was concern with white flight and with decentralization.”

|

|

|

Eichler was deeply concerned with these issues, Lasner says, basing his argument on correspondence in the archives and “my own analysis. [Eichler] did speak very specifically about his concern about the rising cost of land in the suburbs and the changing demographics and urban decay.”

“Multi-family housing as a percentage [of the housing stock] had plunged to its all-time low by the late 1950s. We were churning out single-family tracts. Savvy builders by the end of the 1950s saw that this was unsustainable,” Lasner says.

“They saw the huge baby boom generation would be entering the housing market in the 1960s and not all of them would want to move into [single-family] houses.”

The question before Joe and other home builders was, “How are we going to serve this new market? What is the American city going to look like in the 1960s?”

“[Eichler] decided around 1959 that he wanted to shift the focus of the company to multi-family,” Lasner says. “He did this in a unique way, by leveraging the power he had accrued as a successful developer. And he structured the multi-family program as a kind of experiment. He was certain America needed new kinds of housing in new kinds of places, but he didn’t know what the answers were. No one did.

“The project was to better understand what would work, and what would appeal to different markets -- to baby boomers, to older people. What kind of housing might retain middle-class people in urban areas? What sort of housing did the country need?”

|

|

|

Lasner will discuss proposals for towers and mid-rises in Palo Alto and other suburban locales that were done in by opponents worried about traffic, tall buildings, and black people moving in.

“The race question didn’t come up explicitly in the dialog. But it rarely does,” Lasner says. “Eichler was not a vocal crusader for integrated housing, but everybody knew he sold on an open-occupancy basis.”

Lasner’s research on Eichler, and Eichler’s relationship with Claude Oakland, will be central to his next book, working title 'Bay Area Urbanism.'

“The book is about socially progressive architects in the Bay Area whose work moved the needle on housing to make it more socially just, through mass housing,” the author says.

In essence, Lasner is arguing that, rather than being footnotes in Eichler’s career, multi-family housing was at its core. “Eichler,” Lasner says, “was interested in providing high-quality living to people of all sorts.”

- ‹ previous

- 616 of 677

- next ›