Soul Searching: Photographer, Leland Lee

Throughout his 40 years as an architectural photographer, Leland Lee had one goal in mind—to capture the soul of every building he shot. The soul never dies, but photographs are far more fragile. When fire hits, the soul flits up to heaven. Photos curl and burn.

Lee photographed work by some of Southern California's foremost modern architects and designers, including residences by John Lautner, Pierre Koenig, A. Quincy Jones, Edward Fickett, and John Rex.

Lee, 91, a straight-talking man with piercing blue eyes, a calm manner, and easy laugh, succeeded with his camera because he worked hard, approached his photography as an art, and always sought to bring out what was best in the architecture.

He never let anything stop him—not tough lighting conditions, impossible sites, or tight deadlines—and he always got the job done with a smile. "He had great presence as a gentleman, a lot of self-respect, and also respect for others," remembers Carole Soucek-King, who edited Designers West magazine from 1978 to 1993 and has been friends with Lee ever since.

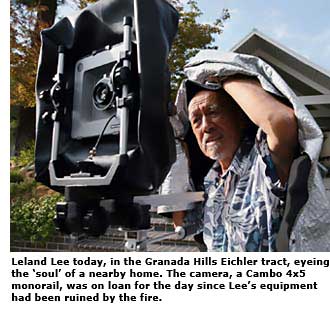

Lee also used to store his photography archive in the garage of his Hollywood Hills home. In the 1980s, a ferocious rainstorm sent sheets of water cascading through his garage, destroying much of his archive of negatives, prints, and transparencies, along with copies of the magazines that had published them and his journals. In 2002, completing the job, a fire that began in his car destroyed the rest.

"About 90 percent of my archive was destroyed in the fire, everything except what I had upstairs in the house," Lee recalls. "The car erupted in flames in the middle of the night."

Other men would have cried. The loss was devastating to Lee. "It represents a legacy of what I did during my existence," he says. But rather than despair, he set off on a quest to recreate his lost archive. "Otherwise, all I have left are fragments," he says.

Lee's archive is of more than personal interest. It would serve scholars and fans of modernism as a valuable resource, a record of modern architecture and interior design from mid-century Southern California.

Lee's search is a daunting task that so far has yielded little. But he perseveres with optimism and energy that surprises many. Lee recently drove to the Bay Area from his Los Angeles home for a social occasion—and to try to find photos he had shot for a San Francisco design firm.

Where other artists might have been devastated by the loss of a life's work, Lee remains philosophical. "Life is so fragile," says Lee, who lost his beloved wife of 55 years two years before the fire. "It can be gone in an instant. People lose everything in a tornado, floods, fire. It's your life that's the most fragile thing of all. I've hung on."

Lee always has.

Life was tough too back in the early 1950s, Lee recalls. After years working in a portrait photography studio in Hawaii, he found himself in Los Angeles with a baby and a wife, who worked days as an elevator operator at I. Magnin. The family was living in Venice in a "minimal, minimal bungalow on the wrong side of the boulevard"—which they shared with one of Lee's boyhood classmates.

Lee, who was attending the Art Center School to upgrade his photography skills, had already suffered one reversal in his career. His hopes to enter fashion photography had been scotched, he recalls, by the discovery that "the fashion industry is not really interested in aesthetics. They're interested in shock."

Instead, Lee found work "developing blueprints in vats of chemicals."

Then his wife spotted the ad, 'photographer wants assistant,' and Lee's life changed course. Lee called, heard the voice, and recognized it—Julius Shulman, the well-known architectural photographer whose voice Lee knew because he'd attended a Shulman lecture.

Of course Lee accepted the job—though he knew little about architecture. "It was economics, see? And of course I knew his reputation," Lee recalls. Lee did have an interest in architecture, however, and had already been introduced to the work of Charles and Ray Eames.

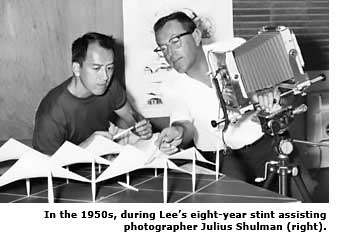

For the next eight years Lee worked as Shulman's "outside assistant."

"I went with him wherever he went and stayed with him while he was out on location. I spelled him while he drove, I set up, packed, developed all the film, took care of supplies." Lee also served as one of Shulman's models and can be seen in some of the master's works.

"Julius had a firm grasp on his stature and reputation," Lee says, "but he was fair and democratic, personally and politically."