Visionaries on the Wing

|

|

|

|

To some people they're just freeways on stilts, "little bits of steel all patched together," in the words of one legendary architect.

But to most of us, bridges are visions of strength and imagination as they spring across the water, sparkle in the sunlight, and glow with illumination.

As the Bay Area prepares to celebrate the reopening of the rebuilt eastern span of the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge, locals can be forgiven for having bridges on their brains.

Just as they did for the 75th anniversaries of the Bay Bridge in 2011 and the Golden Gate Bridge in 2012, people will swarm the waterfront. They will enjoy the light show on the western span and cheer the first cars crossing the new eastern span.

Some will worry about recently discovered structural defects. Others will recall why a new span was needed—the 1989 Loma Prieta temblor that collapsed the eastern span, igniting a fight over building a replacement span that would withstand stronger quakes.

But how many will think of Frank Lloyd Wright, whose quote above described the Richmond-San Rafael Bridge, which was built in 1953?

Or of Wright's own design for a bay bridge he promised "would distinguish and beautify the San Francisco Bay region?"

The design for a concrete bridge, so radically different that its construction would have rendered I-beams obsolete in bridge-building forevermore, so frightened the American steel industry that its leaders successfully conspired to kill the plan.

Or so the oft-repeated tale goes.

|

|

|

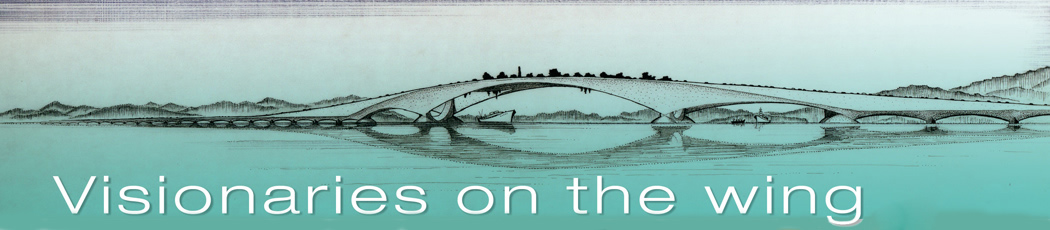

The 'Butterfly Wing Bridge,' as Wright dubbed the late 1940s design, was never built—but it hasn't gone away either.

The story of the Butterfly Bridge is one of missed opportunities and professional tragedy, a forgotten skirmish in what the San Francisco Chronicle called the "Battle of the Bridges," a hard-fought decade-and-a-half war over how and where to build a companion to the first Bay Bridge.

The pre-stressed concrete Butterfly Bridge would have been by far the largest concrete span in the world, anchored in the Bay, using hollow, reinforced concrete 'taproots.'

The bridge's subtle swoop, like the wings of a butterfly, its arched central span with twin roadways separated by a garden where motorists could get out of their cars to picnic and watch the passing ships, attracted immediate attention.

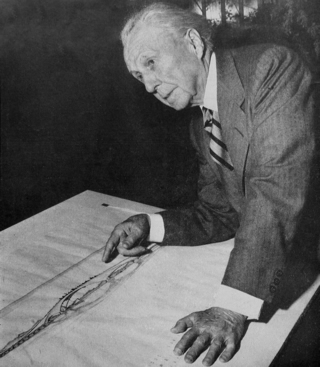

So did its engineering, by the internationally renowned Czech émigré engineer Jaroslav J. Polivka, known as 'Jaro' to his friends. It was Polivka who proposed the collaboration, sending Wright "some notes regarding my idea for the new San Francisco Bay crossing."

"I feel the new crossing would need your creative genius to become the apotheosis of democratic architecture and engineering," Polivka wrote.

|

|

|

Polivka's initial plan, presented to the Bay Bridge's chief engineer in July 1947, was startling indeed, in part due to its immense 3,200-foot concrete span. The engineer, C.H. Purcell, said it was "so far out in front that it sort of staggers us."

Polivka, whose home office in the Berkeley Hills looked over the Golden Gate and Bay bridges, "was always offended by the design of bridges," his granddaughter, Katka Hammond, recalls. "He would grumble about them. He thought there should be a beautiful span across the Bay."

An expert in concrete and structural glass, Polivka had engineered and designed buildings and bridges throughout Europe, including the famous Podolsko Bridge, in Czechoslovakia, whose rhymed arches Polivka illustrated on his stationery for the rest of his career.