Celebrating the Nut Tree’s Modern Design

|

Sometimes modern design sneaks up on people in the oddest of places. For many, that may have included Northern California’s greatest roadside attraction ever, the Nut Tree.

Honored on its 100th birthday in 2021, the late, lamented Nut Tree (1921-1996) was the subject of a lively exhibit, 'Nut Tree Centennial,' at the Vacaville Museum.

The original restaurant, gift shop, airport, and play areas were replaced by a sprawling shopping center, also called the Nut Tree, that does preserve some play structures and décor from the original.

Beginning as a roadside fruit stand in rural Vacaville, the family-run operation (founders Ed 'Bunny' and Helen Power, sons Ed and Bob, and daughter Mary Helen Fairchild) morphed from rustic to modern at the start of the 1950s.

|

There was a spacious restaurant with open-air aviaries that suggest Joe Eichler’s atriums, a gift shop, miniature trains, even an airfield.

For decades families cruising from the Bay Area to Sacramento could stop midway for a well-cooked meal in a well-designed place, enjoy the train and playground, and buy souvenirs – including objects of modern design

“My recollection of the Nut Tree from my childhood was that it was a magical destination spot,” says Marty Arbunich, publisher of Eichler Network, “or, at a minimum, a must-see refreshment stop for so many Bay Area travelers heading to Lake Tahoe and Sacramento.

“How could you pass by the Nut Tree without stopping? After all, the long, hot drive was mostly uneventful…until the Nut Tree. I was always thrilled to stop and take it all in.”

|

Could these visits have contributed to young Marty’s later interest in modernism? It’s worth noting that, in addition to the public buildings of a modern bent on the Nut Tree site, there was also a custom Eichler home, designed by Jones & Emmons and built in the 1950s, that had been commissioned by Bob and Peg Power. It was torn down in the early 2000s.

“Nut Tree was a good example of mid-century modernism in a public commercial plaza,” the historians behind the Nut Tree's Historic American Landscape Survey reported.

“There was a connection between inside and outside through the use of glass. The restaurant space connected to the landscape, which was planted with plants with striking foliage shapes and use of varied materials on the ground. Interior aviaries also brought in light from the ceiling and continued the indoor-outdoor look and feel,” the report said.

The Sacramento architectural firm Dreyfuss & Blackford was behind the buildings, and landscape architect Robert Deering, also from Sacramento, was behind the landscape, which was fully integrated with the architecture.

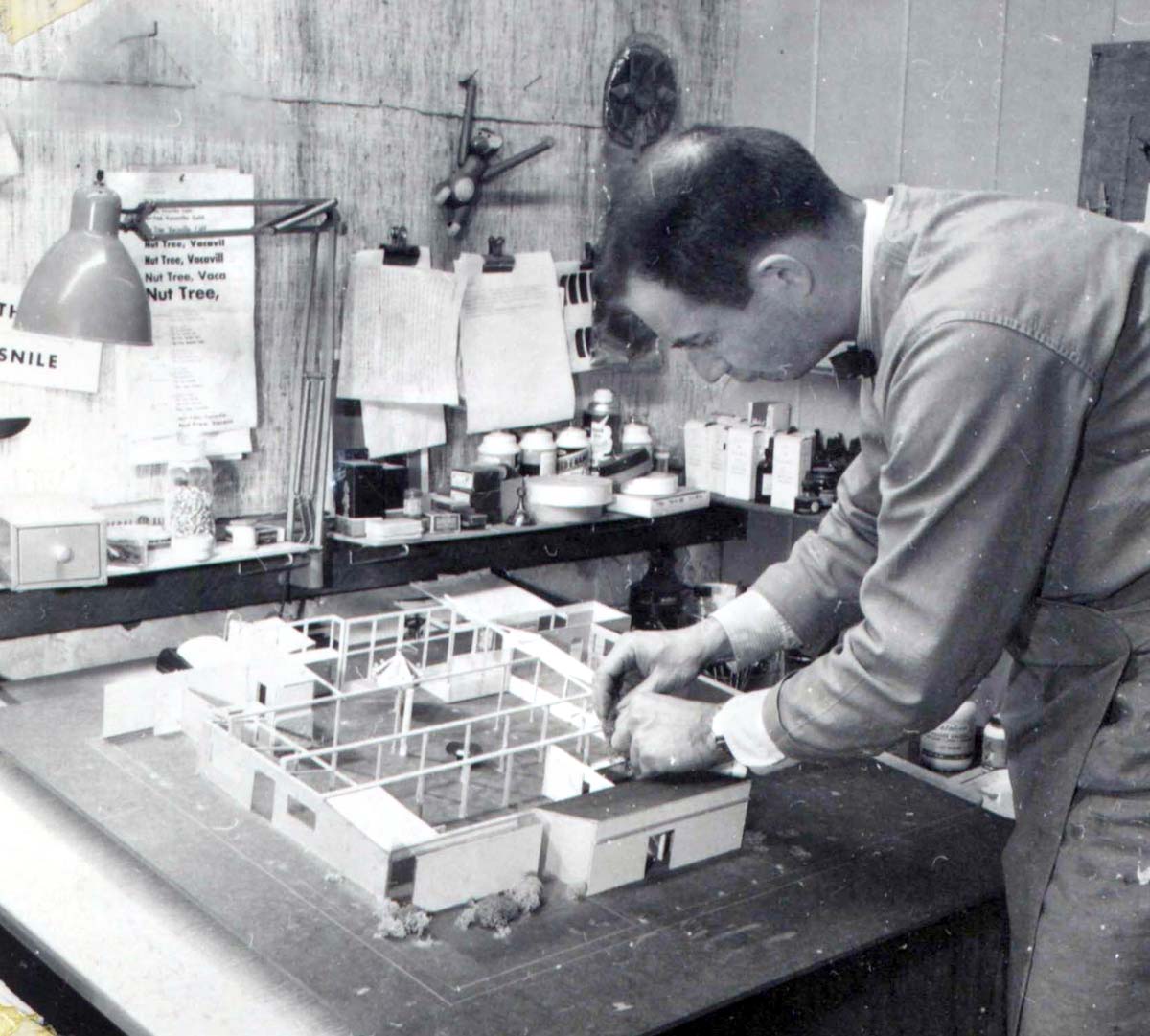

It is artist and designer Don Birrell, who worked for decades for the Nut Tree starting in 1953, who gets much of the credit for the Nut Tree’s look.

|

But Diane Power Zimmerman, Bob and Peg’s daughter, gives ultimate credit not to Birrell, great as he was, but to her uncle Ed, who built modern, glass-walled, adobe homes on site for the family several years before Birrell arrived.

Her uncle was a devotee of the designs of Charles and Ray Eames, which were used in the dining room, in the families’ own homes – and were even sold at the gift shop.

“The Powers looked for ways to make their business modern attractive, and were early devotees of modern design. Nut Tree was the only Northern California distributor of the molded plastic Eames chairs used in the restaurant as well as in their private homes,” museum curator Heidi Casebolt writes.

Indeed, Zimmerman traces the aesthetic tone of the Nut Tree back to her grandfather, Bunny. “It was an aesthetic approach to everything,” she says of the tone he and Helen established. “My grandfather was very artistic. They didn’t just sell fruit, they sold fancy fruit packages that were decorative.”

|

“It was very cutting edge,” says Zimmerman, who wrote the book of celebration, 'Nut Tree: From a California Ranch to a Design, Food, and Hospitality Icon,' in 2021. “It was ahead of its time in everything. We always prided ourselves on being first. Our grandfather and grandmother searched the world for firsts.”

The company insisted that everything, from food to décor to behavior, achieve “the Nut Tree standard.” Young Diane sometimes fell short.

“I had performance evaluations when I was 12. I was told my shoes were too dirty,” she says, laughing. “White tennis shoes that didn’t bleach.”

The Nut Tree, whose mid-century modern designs partook of the whimsical, was all about what later was called “branding.”

“We had a master plan for everything, from the design of the billboards to landscape architecture, from interior design to the way food was arranged on the plate,” Don Birrell told the San Francisco Chronicle in 2000. “We wanted to create a certain feeling, make people remember us.”

It worked.

- ‹ previous

- 124 of 677

- next ›