How Joe Eichler Humanized Modernism

|

|

|

What do Eichler houses mean? I mean, really mean? Psychologically? Economically? Sociologically? What do they tell us about America? About ourselves?

One of the latest thinkers to tackle the subject is a young woman just graduated from the University of Rochester in New York who wrote a paper on the topic that stirs thought.

In the 39 pages of 'Modernism and the Model Home: Joseph Eichler’s Affective Form,' Kathryn Hanlon-Hall delves into such questions as: Was modern architecture of the mid 20th Century “exclusive and elitist?” Was it anti-democratic?

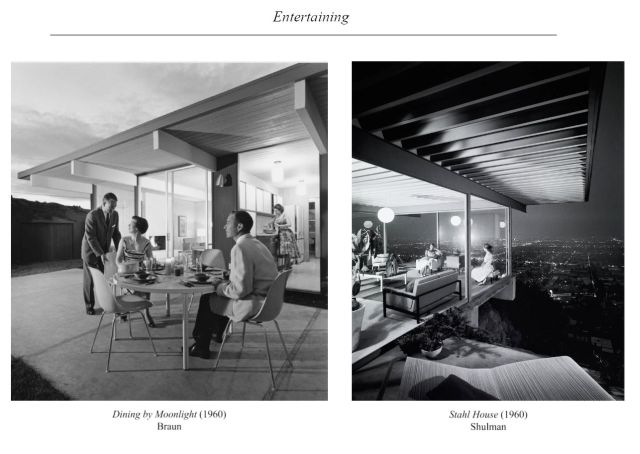

Was Joe Eichler more psychologically attuned to the middle-class mind than the sophisticated architects who took part in John Entenza’s Case Study House program, which produced glass-walled and often steel-framed homes from the 1940s into the 1960s that were publicized as models for modern living in Arts & Architecture magazine?

Did Joe deliberately aim his homes at postwar buyers to alleviate their anxieties, ranging from fear of nuclear war to fear of not attaining a middle-class life? Is Joe partially responsible for 'vanquishing' street life by building homes built around private courtyards rather than open to the street?

Did the design of the Eichler home, with private backyards and atriums, make it easier for him to racially integrate his neighborhoods?

|

|

|

Hanlon-Hall, from San Diego, never grew up in an Eichler home, but she likes them a lot. (Her mother grew up in an Eichler in Orange.)

She described her project as “exploring the connection between the Eichler design (both of the homes and of the neighborhoods) and the success of racial integration within the communities, as well as the specific postwar anxieties that Eichler homes seem to respond to.”

Her paper may be available online once it is published.

In the paper, she argues that Eichler homes succeeded, whereas the Case Study project failed (the sorts of homes that Entenza preferred never hit the mass market) precisely because Joe Eichler was not an elitist.

In this way, she says, Joe also redeemed the entire Modern Movement as it related to the American mass public.

“Conventional wisdom had said that the general American public was turned-off by modernism,” she writes. “This was false; the examples of modernism presented to them simply did not accommodate the demands of the evolving middle-class. Eichler proved that modernism was compatible with the postwar 'American dream,' and perhaps more even compatible with its culture than the eclectic, architect-free designs of ubiquitous ‘box’ developments.”

She argues that the Case Study House program also fell short by not designing entire neighborhoods. (Though several Case Study architects did, including A. Quincy Jones, one of Eichler’s architects.)

Eichler, by contrast, not only designed neighborhoods – he designed neighborly neighborhoods with, quoting one observer, an “old-fashioned Midwestern sort of a feel.”

|

|

|

Hanlon-Hall also contrasts the high-art marketing that characterized the Case Study program with Eichler’s more pragmatic effort to attract the “breadwinning handyman husband and his product-placement wife.”

“Eichler advertisements visually argue that only in spaces as liberating as his is a women truly free to revel in maternal bliss,” Hanlon-Hall writes. “They employ a rhetoric of convenience, mirroring the advertising efforts of Tide, Dodge, and Wonderbread.”

Hanlon-Hall defends Joe’s neighborhoods from criticism they have received from the Bay Area architect Dan Solomon, in which the flavor of a lovely street is ignored in favor of "endless rows" of carports.

Her case, though, sidesteps Solomon’s point – that older neighborhoods of, say, bungalows “delivered beautiful streets, common courtyards, neighborhood communities” by saying these neighborhoods were inhabited by rich people and lacked minorities.

|

|

|

Plenty of nice bungalow-lined streets accommodated working families, back in the day; and in latter days, many accommodate minorities. There was nothing about the design of the communities, but rather discriminatory real estate and lending practices and prejudice, that kept minorities out.

Hanlon-Hall discusses how Eichler was challenged by his desire to sell homes to black people and other minorities, writing, “There is an inevitable thirst in suburban patrons for privacy and a sense that they are sheltered from urban threats. It is no secret that white suburbanites attribute the danger of urban living to its ethnic diversity.

|

|

|

“Even for many white working-class and middle-class owners who only recently ‘earned’ suburban status, the process of integration represented an encroachment of those urban threats on the space to which they had retreated.”

She suggests that the “privacy” provided by Eichler homes may have “mitigated the effect” of black people living near whites.

She writes that anecdotes suggest “that when choosing between retaining their Eichler home and acting in accordance with their racial ideology, most residents put aside their racial contentions. In this bargaining game, the home’s functionality offered a higher payoff to its owner than could ethnic homogeneity.”

There is a lot more that could be said, of course, about how Eichler succeeded in making modernism not just palatable, but desirable, to the hundreds of thousands of people who have lived in his 11,000 homes over the years.

Though he was not the only builder creating modern homes for the middle class, he was the most successful.

As Hanlon-Hall writes, “… this study does not seek to simply praise Eichler Homes, but to use the example of Eichler’s success to discredit the popular notion that residential modernism clashed with middle-class American preferences.”

- ‹ previous

- 324 of 677

- next ›