From War Internees to Iconic Designers

|

The internment of Japanese Americans during World War II is a central point of a hard-hitting, fact-filled, and fast-moving episode of KCET’s ARTBOUND series, 'Masters of Modern Design: The Art of the Japanese American Experience.'

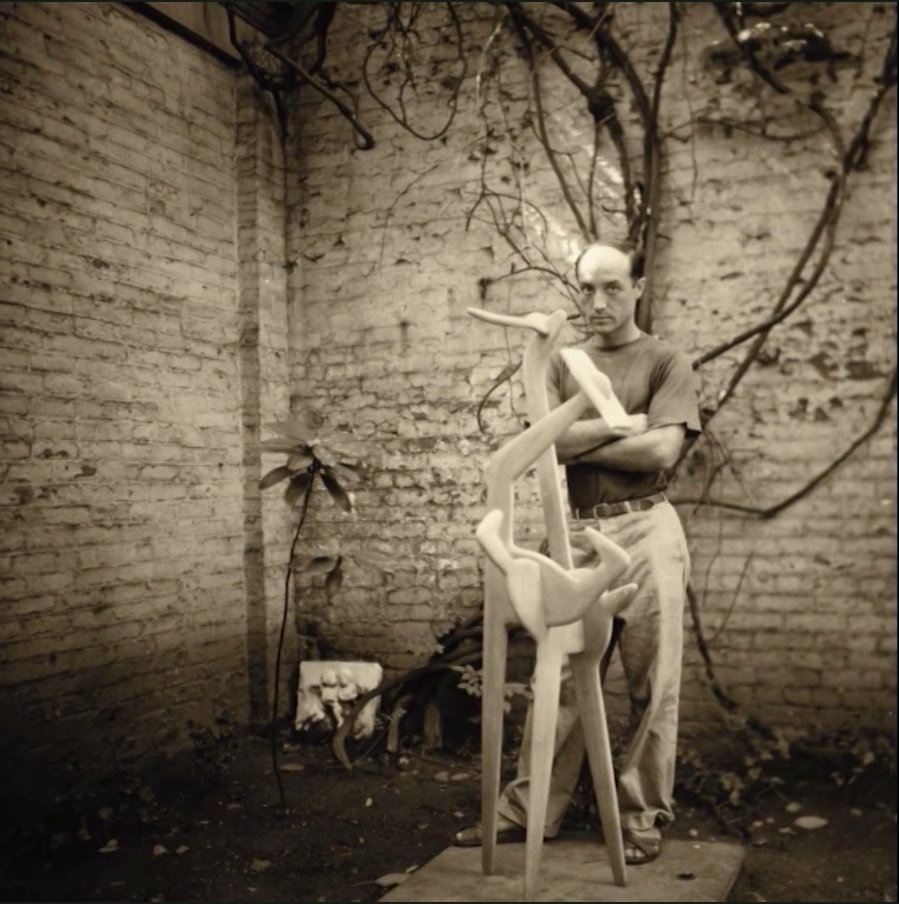

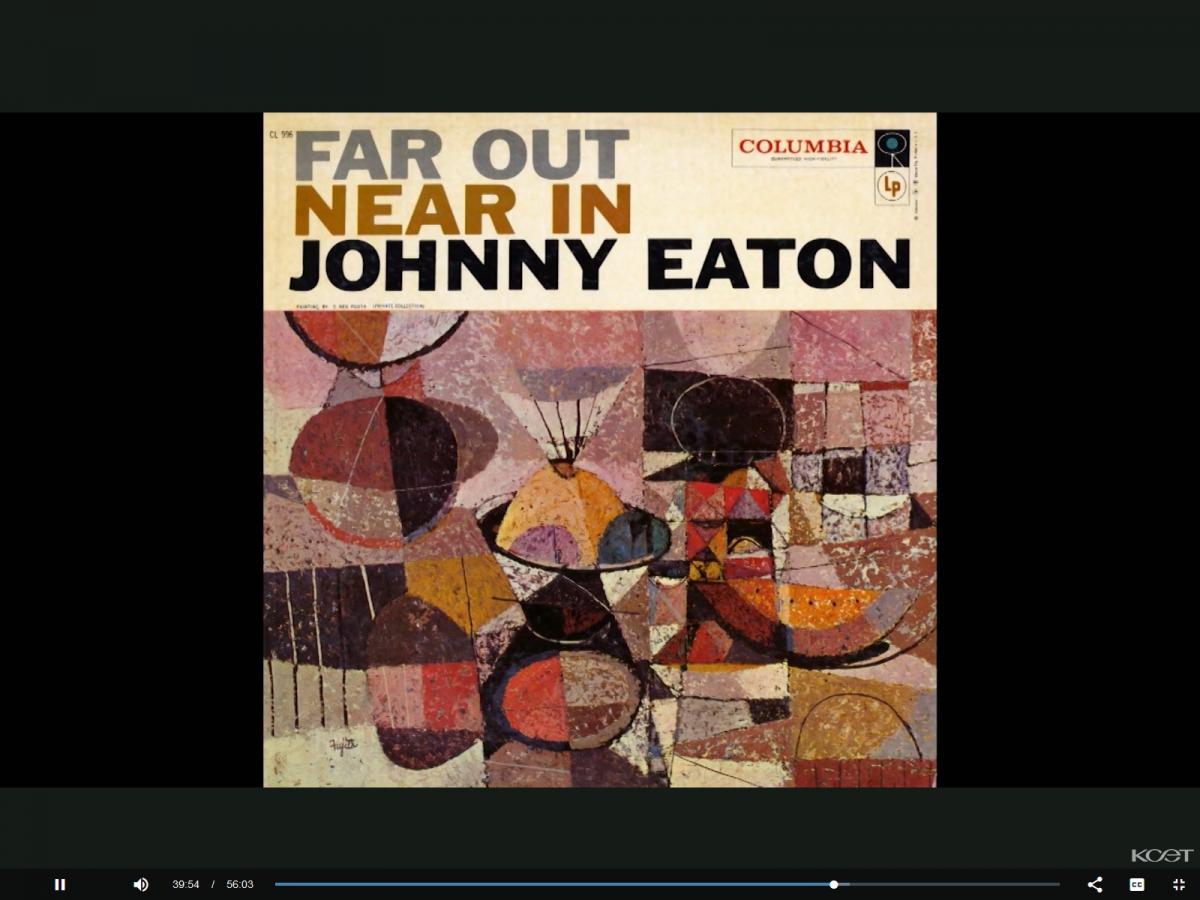

The hour-long film focuses on artist and educator Ruth Asawa, sculptor and furnishings designer Isamu Nogushi, graphic designer S. Neil Fujita, furniture maker George Nakashima, and architect Gyo Obata – Californians all, at least for portions of their lives and/or careers.

Five designers, 60 minutes. The math looks challenging.

Yet by the time we’re through, each artist has come alive. The filmmakers – director Akira Boch and a slew of producers – manage to squeeze in such stories as Isamu Noguchi’s failure to improve life for the Issei and Nisei (first- and second-generation Japanese Americans) prisoners at one camp, where he had hoped to make things livable by providing parks, miniature golf, and more.

|

For one thing, these mostly traditional people did not quite take to a globetrotting, internationally known avant-gardist who had volunteered to live at the camp. Nor did they appreciate that he got to live in his own private cabin while they shared barracks.

“He really thought good design could fix anything,” we are told.

We also learn the tale of Guyo Obata, who as a young man avoided being locked up by winning acceptance at a school in St. Louis. This was away from the coast, where authorities feared fifth columnist would do damage.

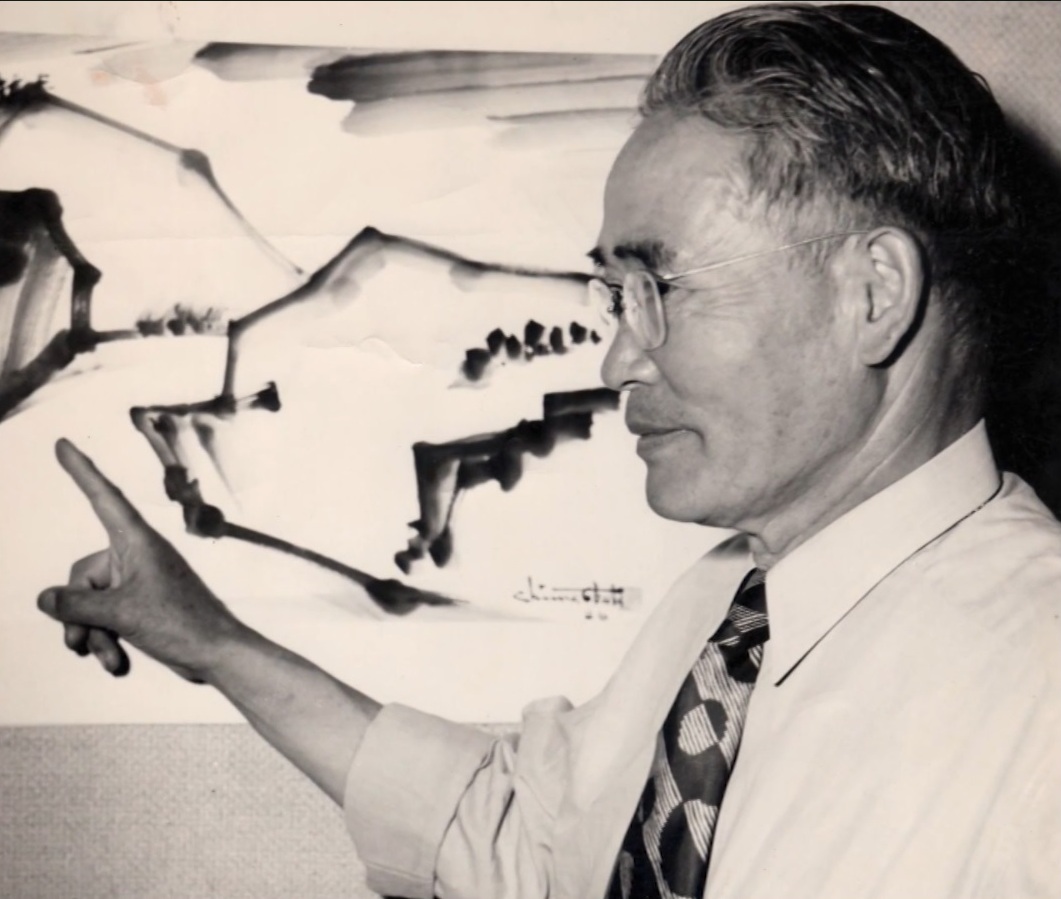

During Christmas Gyo, a free man, got to visit his family in the camp, where they remained prisoners. His dad, Chiuro Obata, who had been an art professor at UC Berkeley, spent time teaching art to fellow internees and turning out artworks that today grace the walls of the De Young Museum in San Francisco. It was, Gyo recalls, “a strange set of circumstances.”

|

Obata went on to found and partner in the firm HOK, ”one of the largest global architectural firms with offices all over the world.”

The ability of young, would-be artists to learn while interned in harsh, often desert condition is remarkable.

In her first, temporary camp, Ruth Asawa learned drawing from three young adults who had also been locked up there. Previously they had been animating Disney movies. She also recalled the devastation of being forcibly removed from her prior life. “We lost farm equipment, horses, we had nothing after that,” she says.

George Nakashima, asked to help make the barren barracks a bit more habitable, first learned to really create with wood in the camp, working alongside a master of traditional Japanese furniture making.

|

Freed from the camp early, when he got an opportunity to move to Pennsylvania to work (temporarily) as a chicken farmer, Nakashima built a cozy home for his small family – so cozy the U.S. government sent photographers.

His daughter remembers posing for pictures, including in her dad’s woodshop: “They were to convince the public that the incarceration didn’t hurt us at all, we were all very happy, successful and so forth.”

As the artists were freed from internment and after the war, racism continued to hurt the lives and careers of Japanese-American creative people. But many bounced back.

|

Ruth Asawa, who studied teaching as well as art because, well, teaching was practical, and she was unable to get a teaching job because of her ethnicity. “So I went to Black Mountain.”

That would be Black Mountain College, sort of like the Bauhaus except in North Carolina, where she studied with such artists as Josef Albers, who had taught at the Bauhaus.

There, she met the modern architect All Lanierand, whom she later married in San Francisco. Black Mountain was a place, we are told, where “you could be an interracial couple and nobody would have a problem with that."

Did the camp experience affect the look of these people’s art? Did it affect the direction of postwar American design?

The film says yes.

|

Nakashima, whose furniture enjoys the wildness of wood, a sort of freeform pleasure, and the joy that comes from imperfection, could only work with what little wood he could find at the camp. And in the early days of rural Pennsylvania he could only afford wood that was imperfect.

There was also a bit of Zen in his work, a way of thinking that was growing popular in postwar America.

“In order to produce a fine piece of furniture the tree lives on, and I can give it a second life,” Nakashima said.

And Ruth Asawa’s signature structures of knotted wire, “like drawing in space...like drawing in three dimensions,” may also hark back to her experience behind barbed wire.

Marilyn Chase, author of ‘Everything She Touched: the Life of Ruth Asawa,’ says in the film: “Wire had been an instrument of her confinement, and she transforms it into a thing of beauty.”

- ‹ previous

- 266 of 677

- next ›