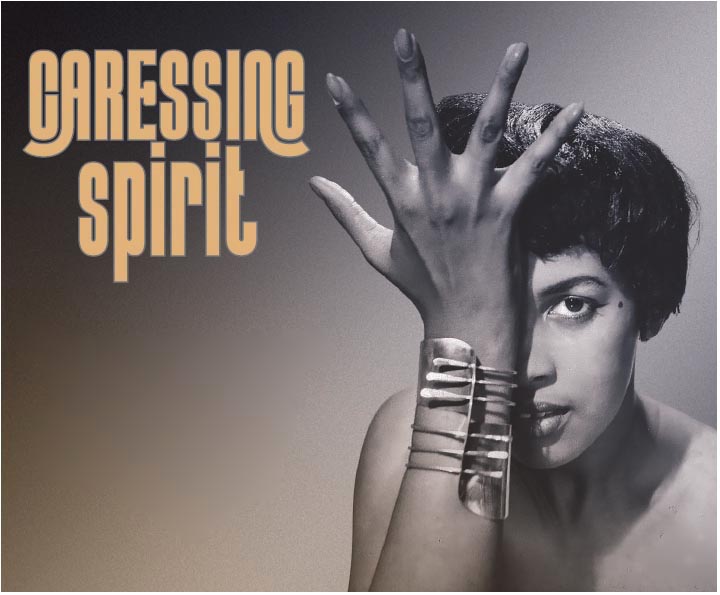

Caressing Spirit

|

|

|

It was a small shop, almost a basement, several steps down from street level in New York's Greenwich Village. But ArtSmith Jewelry, as its proprietor called the place, did not think small.

For more than 30 years, most of it working in a small studio behind his storefront on West Fourth Street, Arthur G. Smith (1917-1982) created what he advertised as 'modern handwrought jewelry' that attracted fans who patronized him for decades, and graced the body of First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt (her brooch was a gift from the NAACP) and the hand of jazz legend Duke Ellington.

The Village, which Smith loved and called "a Little Bauhaus," was a mecca for modern designers, including jewelers, who were pioneering what came to be called the Modern Studio Jewelry Movement.

Modern jewelry was less about precious stone and metals than about personal expression—and Smith got personal indeed, with an approach all of his own that mirrored in many ways his own outsized personality.

His work, as much art as adornment, remains acclaimed to this day, still worn and collected by fans and included in museum collections. He designed for men and women equally, created off-the-shelf pieces and custom work, and often wore his own wares.

|

|

|

According to the founders of the Art Smith Memorial Scholarship Fund, created to further careers of up-and-coming Black jewelry designers, Smith was probably the first commercially successful Black modern jeweler in the United States.

To Smith, jewelry was all about the body, how it moves on the body, and how the body and his art objects interact.

"Pieces should really play with each other, and they should play with the body," he said in a 1971 interview. "A good piece of jewelry literally caresses the body and fondles it. It enjoys itself, and enjoys you, and you enjoy it."

It's not surprising to hear Smith refer to artworks as sentient beings. One of the artworks he created, after all, was himself.

Of Afro-Caribbean background, Smith was born in Cuba and raised in Brooklyn by parents who were originally from Jamaica. Smith studied art at New York's famed Cooper Union, and got into the jewelry business as a fabricator for an experienced modernist Black jeweler, Winnie Mason.

|

By the mid-1940s Smith was an integral part of the Bohemian scene in the Village and beyond, hobnobbing with Black artists and intellectuals, like writer James Baldwin, dancer Talley Beatty (whose friendship led to much design work for Black dance and theater companies), and singer/activist Harry Belafonte.

Smith set up in the Village in 1946, just as modern jewelry was appearing on the map, thanks in part to the Museum of Modern Art exhibit 'Modern Jewelry Design 1946-47.'

His shop became an attraction.

"Stepping down the few steps to his West 4th Street display room and workshop, you felt all the astonishment and pleasure of [fictional character] Ali Baba entering the gleaming treasure trove of the 'Forty Thieves,'" Mel Tapley of the New Amsterdam News recalled, when years later he was called upon to write the artist's obituary. Tapley, a cartoonist, editor, and NAACP leader, was Smith's friend from Cooper Union.

Smith was openly gay (at least to his compatriots), and friends included such gay creatives as composers Lou Harrison and Billy Strayhorn, Ellington's collaborator.

|

Smith was a lifelong jazz devotee, served as president of the Duke Ellington Society, and when one of his boyfriends dropped Smith to take up with Strayhorn, "Arthur actually felt pride in the fact. Strayhorn was one of his heroes," Charles L. Russell, Smith's longtime partner, wrote.

'Smitty,' as some friends called him, dressed conservatively when he had to, but was always well-coiffed and showed flair. Russell, who wrote a book on the jeweler, recalled "Art's penchant for wearing flamboyant clothing punctuated with jewelry," mentioning "mustard yellow trousers with inch-wide white stripes and a blousy pirate-style shirt."