Was ‘Little Boxes’ Fair to Suburbia?

|

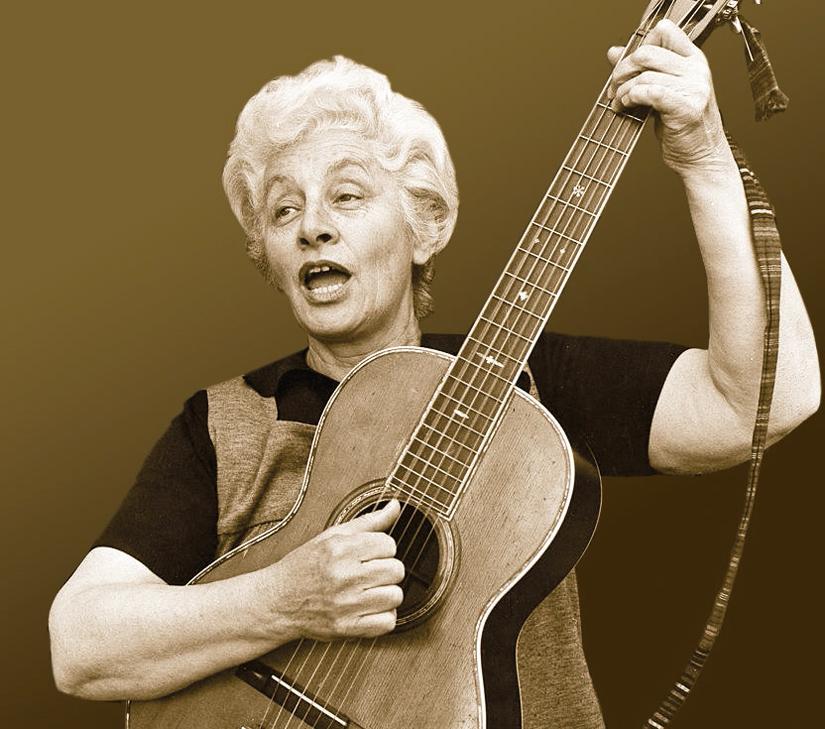

Folksinger and songwriter Malvina Reynolds did not have Eichler houses in mind when she penned her soon-to-be hit song ‘Little Boxes’ in 1962. The song, a putdown of suburbia and its people who, like the house, “all look just the same,” is now celebrating its 60th anniversary. Writer Carol Sveilich, who grew up in an Eichler, reflects on its meaning in 'Echoes of ‘Little Boxes,’' in the new, winter ’22 issue of CA-Modern magazine.

Malvina Reynolds was born in San Francisco in 1900 -- the same year as Joe Eichler. The daughter of Socialist parents, she studied at UC Berkeley and lived in Berkeley for many years. Besides being a singer-songwriter, she was an activist for left-wing causes her whole life.

For a time she was involved with San Francisco’s Labor School, where Eichler’s architect Bob Anshen had earlier taught.

Reynolds wrote many songs and performed widely, and near the end of her career – she died in 1978 – was among the cast of ‘Sesame Street.’

But it was with ‘Little Boxes,’ written while she was a passenger in a car going through Daly City, the town immediately south of San Francisco, that she most made her mark. It was a worldwide hit as sung by Pete Seeger, added the term 'ticky-tacky' to the dictionary, and has been covered by such stars as Elvis Costello and Donovan.

|

As Will Swaim wrote two years ago in the National Review, in a lively piece called ‘The Folk Song That Slandered California’s Suburbs’:

“In little more than the time it took to write it, ‘Little Boxes’ blew the lid off folk music. Reynolds loaned it to her friend Pete Seeger, who, in an irony of market efficiency that has bedeviled such revolutionary artists as Gang of Four, the Clash, and the Situationist International, took the song to boffo global sales and luxury-level royalties.”

Henry Doelger, who built the Daly City homes that apparently inspired the tune, hated the song, Doelger’s late architect Ed Hageman has said.

But does suburbia as a whole, and do the particular Doelger homes that inspired Reynold’s ditty, deserve this opprobrium?

In her essay, Sveilich, who was raised in the Eichler San Jose tract of Fairglen, suggests not. She points out that Doelger built his homes out of redwood, not ticky-tacky, and provided “a variety of floor plans -- as many as twelve. [The homes] contained high-end finishes, and all the front facades and colors differed."

|

Indeed, Doelger went out of his way to create a varied streetscape. Sveilich speaks to another Doelger fan, Rob Keil, who wrote the 2006 book ‘Little Boxes: the Architecture of a Classic Midcentury Suburb,’ about Doelger’s Westlake development.

“As a kid, I was impressed that they were more interesting and quirkier than they were the same,” Keil tells Sveilich. He adds that the Doelgers of Westlake had a “modern pop style -- a fun sort of modernism.”

“There would be a variety of planned styles and colors in each row of homes,” Keil said. “Walking down the streets of modest homes in Westlake was a bit like walking down Main Street at Disneyland.”

In its essence, though, the song was not about residential architecture. Rather, it used that architecture as a metaphor to rip into middle-class society and conformism, likening the samey samey lives of the people who lived in these houses to the blandness of the architecture itself.

|

Sveilich writes: “Keil and many others believe Malvina Reynolds’ song was making a statement about postwar conformity and the need to be and look ‘normal.’ In the 1950s and early 1960s conformity was ‘in.’ However, Reynolds’ ditty soon became a theme song for poking fun at middle-class normalcy.”

In Swain’s take on Reynolds and her song, “The apparent placelessness, homogeneity, and sameness of suburban planning produce blunted humans, and those humans must be liberated by a vanguard of enlightened artists, workers, and bureaucrats.”

Swain ties the song to a wider and never-ending penchant by some academics to bash suburbia. But as anyone who has lived in an Eichler neighborhood, for example, knows, it’s not always all that bad.

Decide for yourself after perusing 'Echoes of ‘Little Boxes’' in the new, winter ‘22 issue of CA-Modern magazine.

- ‹ previous

- 619 of 677

- next ›