It Came from Outer Space

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

What wielded that irresistible grip on the minds of America’s baby boomers in the mid-century? What pulled them into libraries, comic book stores, and movie theaters?

What was so powerful that it even crept inside the minds of their parents, distracting them from the lingering pain of World War II, and from the impending threats of the Cold War and nuclear devastation?

It could only be science fiction.

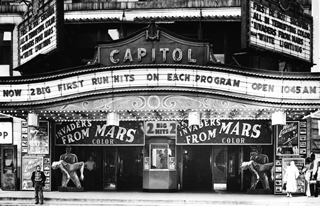

Through science fiction, beginning in the early 1950s, the movie theater became America’s vehicle to alien worlds, and to invasions by aliens in our own world.

Back then, it was Saturday’s creepy double-feature matinee that pulled us in. When the house lights went down, we munched on popcorn, and squirmed and giggled—and shrieked. Afterwards, shaken and exhilarated, we dashed home, ever so wary of twilight’s sinister shadows that lurked at every turn.

While the movie theater had become a familiar and convenient place to channel our fear and loathing into habitual weekend thrills, sci-fi movies were turning our nightmares, and our parents’ anxious daydreams, into good moneymaking entertainment.

It was a creative boon, too, for the men and women who’d been working within the sci-fi genre for some time, and would continue to, into the next millennium.

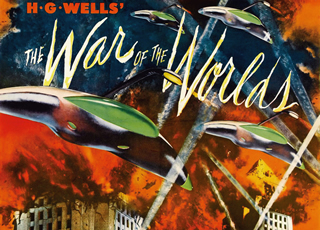

Despite pioneering contributions from France’s Jules Verne and England’s H.G. Wells, science-fiction and fantasy novels had been “marginalized” earlier in the century, according to Professor Robert Gorsch, who conducts a course in those genres at St. Mary’s College in Moraga.

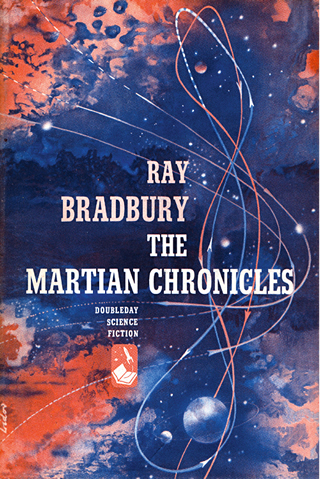

In the popular culture of the 1920s and 1930s, sci-fi stories by authors such as Ray Bradbury and Robert Heinlein had begun appearing in electronic hobbyist magazines, before they spawned their own genre-specific ‘pulp’ magazines. Science-fiction heroes Buck Rogers and Flash Gordon were transported from the pages of comic books to movie screens in the ‘30s with interplanetary adventures played out in serialized short films.

But with World War II, the space travel and deadly rays of sci-fi seemed to be taking real form. “Science fiction writers and readers felt they’d been vindicated,” says Gorsch, “because liquid fuel rockets had been flown and nuclear energy had been released,” in the form of Germany’s V-2 combat rockets and America’s A-bombs, respectively. “It’s not that fans celebrated the bomb, but omigod, it was all true now.”

Wernher von Braun, the designer of the V-2, “was a space travel buff before he was ever a weapons maker,” says Gorsch. And America’s space program, which employed von Braun under the direction of a newly created National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), was “fed by science-fiction dreams.”

The dreams of children in the ‘50s were illuminated by easily available and affordable comic books, with their depictions in color of mighty, sexy heroes and heroines; awesome spaceships, weapons, and devices; and sound effects like zap! pfft! and kaboom! bringing the action to life.