Have a Mid-Century Modern Movie Night

|

Chafing dishes, Eames chairs, tabletop rotisseries, an electric can opener, earthmoving equipment, and homes with “walls of glass merging room with room, blending inside with outside” are caressed by the cinematographer’s lens in a delightful little film sure to entertain the 1950s-philes among us.

'American Look,' from 1958, long enough to fill a half-hour TV slot with time for a couple of cigarette commercials, promotes itself as “a tribute to men and women who design,” and as “an appreciation of the stylists of America.”

In truth, though, what the film promotes more than the designers – who are often shown but never named – are the goods they produced, which are shown but not attributed to any designers by name.

Have fun calling them out, you design mavens in the audience.

|

“In form, proportion, rhythm, and variety, the stylists leave their unmistakable marks on everyday conveniences in flow, line, and graceful shapes which we as Americans may enjoy.”

Eichler homes, unfortunately, do not make their way into this film, which does show several attractive homes of the mid-century modern variety. The work of two of Joe’s architects, Bob Anshen and Steve Allen, does appear, however.

Anshen and Allen are represented with their Chapel of the Holy Cross, mystically sited amidst rocky crags in the mystic community of Sedona, Arizona.

The film has that wonderful optimism so often heard in the 1950s. It was a brand-new age of design, the narrator tells us, and nowhere more so than in the U.S.A. Yep, a bit of Cold War propaganda creeps in, but that was the way it was back in the day.

|

“Women and men alike are increasingly interested in the look of things,” we are told. “They eagerly give their attention to what’s new and beautiful and advanced.”

The narrator praises Americans’ “ever-improving good taste,” and applauds the “wondrous possessions which have new grace and glamour and are offered to the American people.”

It takes a while to realize that this cinematic delicacy, which was unearthed by San Francisco’s Prelinger Archives, is an infomercial for General Motors.

But there we are as the film nears its end inside the General Motors Technical Center, designed by Eero Saarinen, watching men and women sculpt Chevrolets out of clay and fiberglass in gorgeous open-planned buildings while lounge music swirls and couples immaculately dressed for business enter their workplace past a car that looks more like a spaceship.

|

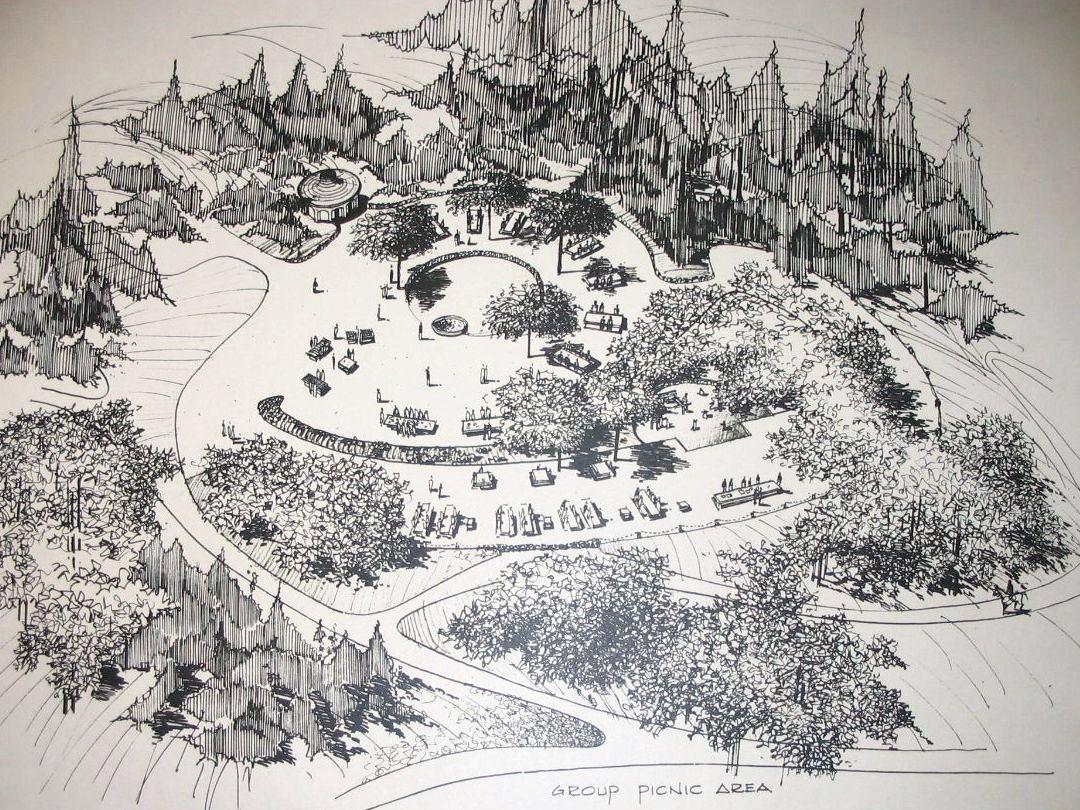

Closer to home is an 11-minute film that will take you to a place many of us already go, Mitchell Park in Palo Alto, which is within walking distance of scores of Eichler and other mid-century modern homes.

But it’s a different experience viewing ‘A Community Park’ because the film was made circa 1956 on behalf of the men who designed the park, Royston, Hanamoto and Hayes Landscape Architects, and narrated by Robert Royston, the head of the firm.

(Royston did much landscape design for Eichler homes over the years.)

The film came to the Internet Archive through UC Berkeley’s Environmental Design Archive.

Royston and his associates always saw their designs as more than prettifying the landscape, or even making it more functional. They saw landscape architecture as a way of improving society, and the film early on shows row after row of suburban house gobbling up land without providing playing space or outdoor areas for adults.

|

“Where else can these girls talk but the street?” the narrator asks over a shot of two young things conversing while sitting on a curb.

This is said, of course, to point out the necessity of such public parks as Mitchell Park. Royston throughout his career designed parks, including Central Park in Santa Clara and Cuesta Park in Mountain View.

(Eichler’s Greenmeadow subdivision, by the way, did provide a park and a swimming pool for its residents; it is very close to Mitchell Park and its first houses were built a few years earlier.)

The film shows the hands of the landscape architects at work on park drawings, and there are lively shots of little children playing in Royston’s innovative and signature play structures, including bear sculptures and 'gopher holes' in concrete structures allowing kids to hide and then pop up through.

In a 2006 interview with the author of this blog post, Royston discussed the roots of this charming little film. He explained that the film came about because the wife of one of the firm’s young architects “followed [the park process] with a camera, which was kind of wonderful because we made a movie of it.”

“It was about what a modern park should be,” Royston said.

While changes have been made to Mitchell Park in the interests of modern safety, its historical aspects have been maintained and restored. This park remains a favored place for people of all ages, as its designers planned.

- ‹ previous

- 294 of 677

- next ›