‘Neon Speaks’ Goes Worldwide in 2020

|

Havana is known for its beaches, its friendly people, Art Deco architecture, and old clunker cars from the 1950s that owners keep going forever with repair after repair after repair.

But vintage neon signs from the period did not fare so well – although recently many have returned to life after being dark and dilapidated for decades.

Adolfo Nodal, who has helped restore most of them, is just one of a broad international crew who will entertain and educate neon professionals, neon fans, and the general public at the third annual Neon Speaks conference, which is based in San Francisco but will take place virtually this year over two weekends, September 25-27 and Oct. 3-4.

“We’re going to be talking about neon restoration around the world, some of it on Cuba,” says Nodal, who will be 'attending' his first Neon Speaks.

|

“We are bringing back neon to Cuba,” he says. Nodal both restores neon as a business in Cuba and Los Angeles, where he is based, and as a passion. He works with artists and neon fabricators in both places; he is not a tube bender himself.

He is also a tour operator for a living, including neon tours of Havana, which are on hold during the COVID pandemic. Nodal, who started restoring neon back in 1984 in Los Angeles, is a pioneer in the field.

“When I started,” he says, “people thought I was crazy. They saw the signs as junk, basically, on top of buildings."

His firm, Habana Light Neon and Signs, has restored about 100 signs in the Cuban capitol. “I did it really to bring neon back in Havana,” Nodal says.

|

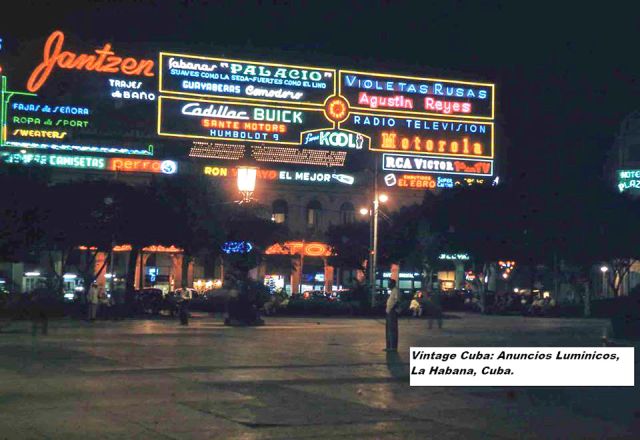

Neon arrived in Cuba in 1921, the same year it arrived in Los Angeles, after its invention in France, he says.

“Neon became like a symbol of modernism. Cuba had more neon signs than New York at a certain time. There were streets in Havana where you couldn’t even see the sun, they were so full of signs,” he says.

“Neon signs are like the 1950s cars, the old cars. The neon signs are the architectural equivalent of that. The signs were on the buildings and the cars were on the street.”

But with the coming of Fidel in 1959 and the closure of casinos and other pleasure palaces, neon was no longer appreciated. The cars remained because people had to drive.

But what cigar-chomping socialist revolutionary needs flashing Coca-Cola signs?

“A lot of [the signs] had brand names, images the Revolution didn’t want any more, names of American companies,” Nodal says.

|

The signs deteriorated. “Cuba is tropical,” he says. “It’s hard to maintain them.” Oftentimes metal from the neon signs was scavenged to repair the similar era cars.

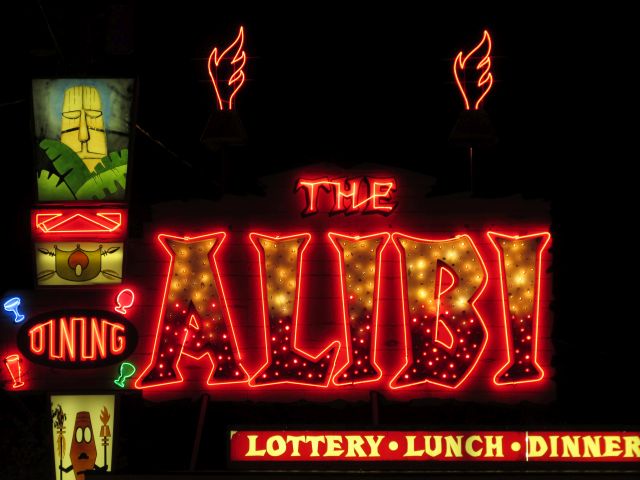

Today, restaurants throughout the city have restored or new neon, and Nodal and crew have restored neon for many old cinemas that are no longer in business – just to put some flash into the landscape.

Nodal, who is in Los Angeles during the pandemic, remains involved with neon there, working with artist Troy DiPietro to create what he calls “a beautiful neon space” at the entry to a downtown tunnel.

Last year the festival, whose venues included the Great American Music Hall, attracted approximately 100 attendees, about the same as the first year, says Al Barna, who organizes the event with Randall Ann Homan. They call their organization San Francisco Neon. This year they already have more than 400 registrations.

“The upside of an online festival is the potential to bring together a larger group of preservationists, including those who can't easily traipse across a bridge, hop on a plane, or cruise down the highway to San Francisco and join this crowd of like-minded people,” Barna and Homan write.

|

Barna tells us: “We don’t want to turn anyone away.” Fans can buy an "All-Event Virtual Passport" on a sliding scale starting at $10. Partnering with San Francisco Neon on the event is the Tenderloin Museum and the Museum of Neon Art. San Francisco Heritage and the National Trust for Historic Preservation are among the funders.

Other international events will focus on Poland with an hour-long film. “It’s one of the most beautiful films on Polish neon,” Homan says. After the film fans can ask questions of the director, who will be Zooming in from Warsaw.

Great neon-type designers will attend from Portugal as well. "The Letriero Galeria Projecta has been saving neon signs all over Portugal," Homan says.

In Communist-run Poland, Homan says, neon played an entirely different role than in the Capitalist U.S. or Cuba.

“Havana was all about nightclubs and party time and Americanism,” she says. “But Soviet [era] Poland was so bleak. The government paid for neon all over Poland just to brighten the street. They were not advertising brands. The designs were unbelievably beautiful.”

Some events go beyond neon, including 'Signs, Streets, and Storefronts,' a presentation by Martin Treu, a professor in Chicago. “He is passionate about saving Main Street,” Homan says. She notes that local shops that add so much to our landscape and lifescape are endangered by pandemic closures.

“We’re deepening the conversation,” she says. “But neon is always there. It shines on a lot of different aspects of the conversation."

- ‹ previous

- 676 of 677

- next ›