King of the Flat-tops - Page 4

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

No bank would finance the house. "The neighbors even had a petition against it," Geoff says. Smith found himself standing in front of the home one September day listening to a broker explain why he wouldn't list it.

"The appearance, especially the flat roof, was too unusual to sell, and the price was too low to make it worthwhile," the Post wrote. Then, the story continues, "A red convertible pulled to a stop, and the young woman driving called out: 'That house is darling! If it's for sale, I want to buy it."

'Flat Top' Smith was on his way.

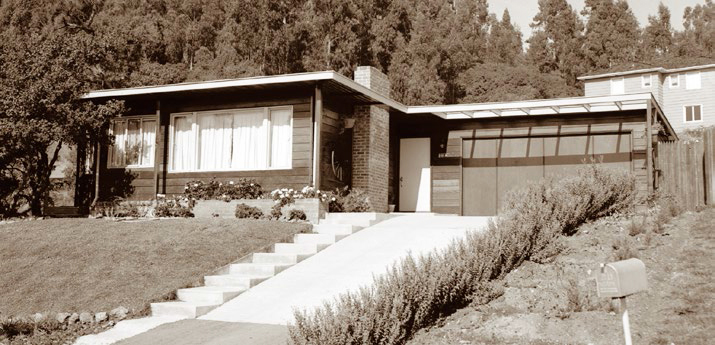

Over the years Smith produced models with varying floor plans, facades, and even rooflines. His homes were sheathed in redwood or stucco or both. Earlier models often had some brick sheathing.

The homes had attached carports or garages. Decorative angled posts or latticework screens and trellises often embellished the façade. Wood-framed windows facing the street were often grouped in sets of three or four. Large windows faced the rear yard, and some models had window walls, like Eichlers.

Inside, the plan was relatively open, with shared living and dining areas and small kitchens. Smith eschewed hallways as a waste of space. Ceilings were tongue-and-groove redwood or fir, and there were open beams. Although he used a concrete slab rather than a traditional foundation, Smith, unlike Eichler, opted for wall furnaces, not radiant heat.

Homes ranged from 750 to 1,000 square feet in the early days, growing larger as the years went on. Smith occasionally built larger, luxurious versions of his basic plan, including five for executives of his firm in the upscale town of Alamo.

Many builders throughout Northern California bought plans from Smith. "So there are flat-top subdivisions that are dad's houses, but they were not built by him," Geoff says.

What made the homes special was less the aesthetics than the techniques. Smith developed, or worked with others to develop, innovative ways to create an impermeable concrete slab to prevent the seepage of moisture. It involved concrete footings, a layer of pea gravel, and then "they mopped on hot tar, which formed a barrier that kept capillary action out," Duncan says. A layer of heavy felt covered the tar, followed by reinforcing mesh and the concrete.

The characteristic flat-topped roof was not absolutely flat, but slightly pitched for drainage.

By the late 1950s or early 1960s, some of Smith's homes had low-pitched gables as well as exposed exterior beams, Duncan says. And the flat roof was losing its appeal to buyers.

By the mid-1960s, Duncan says, 'Flat Top' Smith had dropped his signature flat roof. "That's when they came out with the engineered truss [roof] with metal gussets. Dad crunched the numbers and determined it was a less expensive roof to put on with a pitch and cover it with tar and gravel."

Earl Smith, who stood six feet tall and carried 220 pounds, was "an imposing man," Geoff says, adding, "Dad was a dictator. Not like Adolf Hitler or Mussolini, but he pretty much liked telling people what to do. He had a big ego."