Miraculous Murals Hide Within a Berkeley Brown Shingle

|

|

|

From the outside it appeared to be a typical early 20th century Berkeley brown shingle house. Inside, however, the former home of cineaste Pauline Kael is a trove of mid-century murals by the legendary artist Jess. And the house will soon be for sale.

Kael, who wrote film criticism and helped run Berkeley’s famed Cinema-Guild Theater, a repertory house on Telegraph Avenue, in the 1950s, turned her nearby house at 2419 Oregon Street into a Bohemian hangout, attracting writers, artists, Marxists, a pretender to the throne of Russia, the filmmaker Jean Renoir, poet Robert Duncan, and Duncan’s partner Jess.

The sale of the house, and of the murals within, raised intriguing questions, in part because, as the listing agent Ortrun Niesar of Sotheby International Realty’s Berkeley office said, “Some people have said it’s likely the murals are worth as much or more than the house is worth.”

|

|

|

Niesar, a student of art history who has worked in museums, approached her task carefully, bringing in art dealers, art conservators, art valuators, and other experts as needed. She also worked closely with Christopher Wagstaff, co-trustee of the Jess Collins Trust, who organized an exhibit and catalog on ‘Jess, Robert Duncan and their Circle.’

Jess’s murals filled most of the upstairs rooms and small portions of the downstairs. Abstract decorative works, including a colorful, checkerboard pattern floor, were done by another artist who was part of the circle, Harry Jacobus. Niesar says Jess did his murals over a short period in 1956.

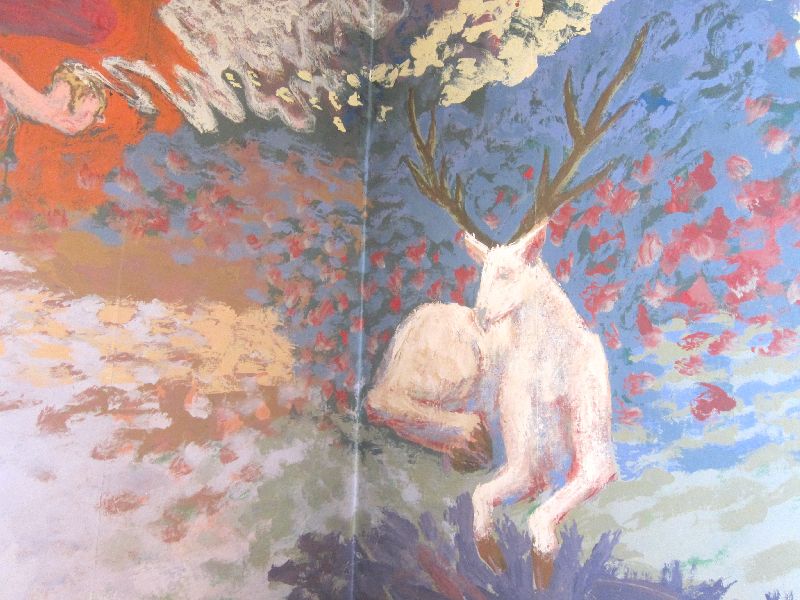

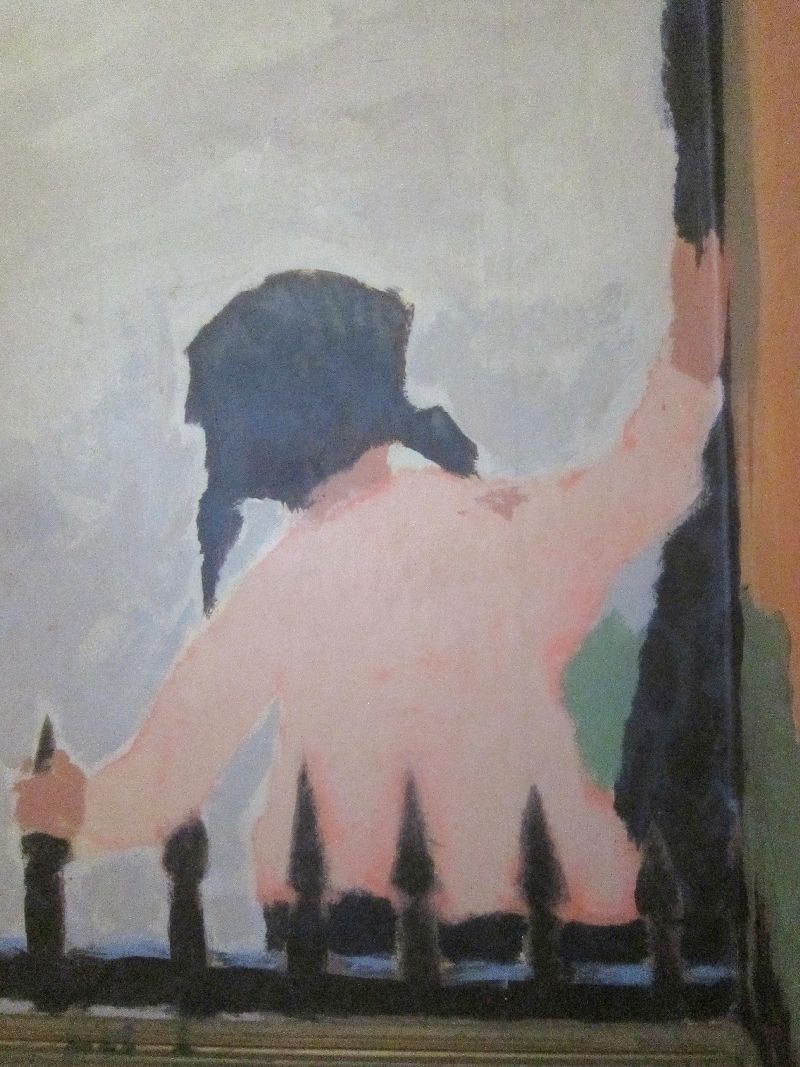

There are rural landscapes, a muse, a stag, an image of Kael’s young daughter looking into a fantasyland, classical imagery above doorways, and Cubist abstractions.

Several upstairs rooms and ceilings have been painted over, but Niesar believes the murals exist beneath the paint and restoration might be possible.

The house, a “classic Berkeley brown shingle,” in Niesar’s words, was about 2,700 square feet with four bedrooms, had a backyard cottage, and structurally sound. Inside, some rooms had original board-and-batten walls; some were mid-century modernized in the 1950s with Eichler-style plywood paneling.

Besides the presence of the murals, the Kael house had historic importance because of Kael’s place in cinematic and literary history, and because it was an important center for intellectual and artistic activity in the 1950s.

|

|

|

It also played a role in gay history as one of the haunts of Jess and Robert Duncan, mainstays of the still largely underground gay culture of the time in the Bay Area. Duncan, who was educated at UC Berkeley, as was Kael, wrote an early gay rights manifesto in 1944, 'The Homosexual in Society,' defining homosexuals as a repressed minority, like blacks. It was not a common idea at the time.

Writer David Pollock recalled first coming upon the scene at Oregon Street in the 1950s, in a California Monthly article from 2003:

|

|

|

“Pauline was in the position she occupied permanently in the house at all hours – hovering over a heap of manuscripts, scribbling loudly with pencil in one hand while alternating sips of Scotch and puffs of Camels with the other, and emitting little sounds of concern.”

Jess (originally Jess Collins) became an artist after a dream suggested the world would come to an end in 1975. He quit his job – working on atomic weaponry at the Hanford Project – and was soon producing quirky, dreamlike, and colorful abstract and narrative art.

He did murals in several houses, including the one he shared with Duncan. But only these murals remain essentially intact, Niesar says.

“What I always wanted to do,” Jess told curator Michael Auping in the early 1990s, “was make the image in flux so that at any given time you could see a woman or an enchanted landscape.”

Jess was inspired by water stains and cracks in a house’s walls. “I can’t help staring at them and making pictures or fantasy images out of them,” he said.

Wagstaff wrote to supporters, suggesting that the house could be bought and preserved “by an individual deeply committed to caring for Jess’s and Jacobus’s artwork,” or preserved as a museum or “an adjunct to a library or academic department.”

|

|

|

"We must stress the urgency of the situation,” Wagstaff writes, “and the need to act somewhat quickly; there were only several weeks to arrive at a plan to preserve this unique and historically significant Berkeley structure.”

“The family would be thrilled if the home could be turned into a center for research, study, and reflection,” Niesar said of the owners, children of a couple who have owned the house since the 1960s.

“The best [outcome] would be if the house became a permanent part of the Berkeley heritage,” Niesar says.

- ‹ previous

- 410 of 677

- next ›