Should We Stop Calling Them 'Eichlers'?

|

|

|

Now that San Francisco leaders have renamed Justin Herman Plaza to stop honoring a man whom many blame for removing African- and Japanese-Americans from the Western Addition in favor of gentrification, let’s consider the case of another man who took part in the city’s redevelopment of the neighborhood – Joe Eichler.

Late last year, the city’s Board of Supervisors decided that Justin Herman, who ran redevelopment in the city in the 1960s, was no longer deserving of the honor. They’re calling it ‘Embarcadero Plaza’ for now.

Herman ran the city agency during the time when many black and Japanese-American residents of the Western Addition were driven from their homes by bulldozers. Although officials promised to make major efforts to re-house displaced residents once the area was reconstructed, relatively few people returned.

London Breed, who was president of the board when the name got changed and is today mayor, said the neighborhood, where she grew up, “was literally destroyed by the San Francisco redevelopment agency.”

|

|

|

The supervisors weighed in against Herman unanimously; the city’s Recreation and Parks Commission agreed on a vote of 4-2.

But how about Joe Eichler, who eagerly worked with Justin Herman and redevelopment on several major projects, both at then-undeveloped Diamond Heights, and in the heart of the Western Addition?

Should he be pilloried too for displacing minorities? Should we stop calling his homes Eichlers?

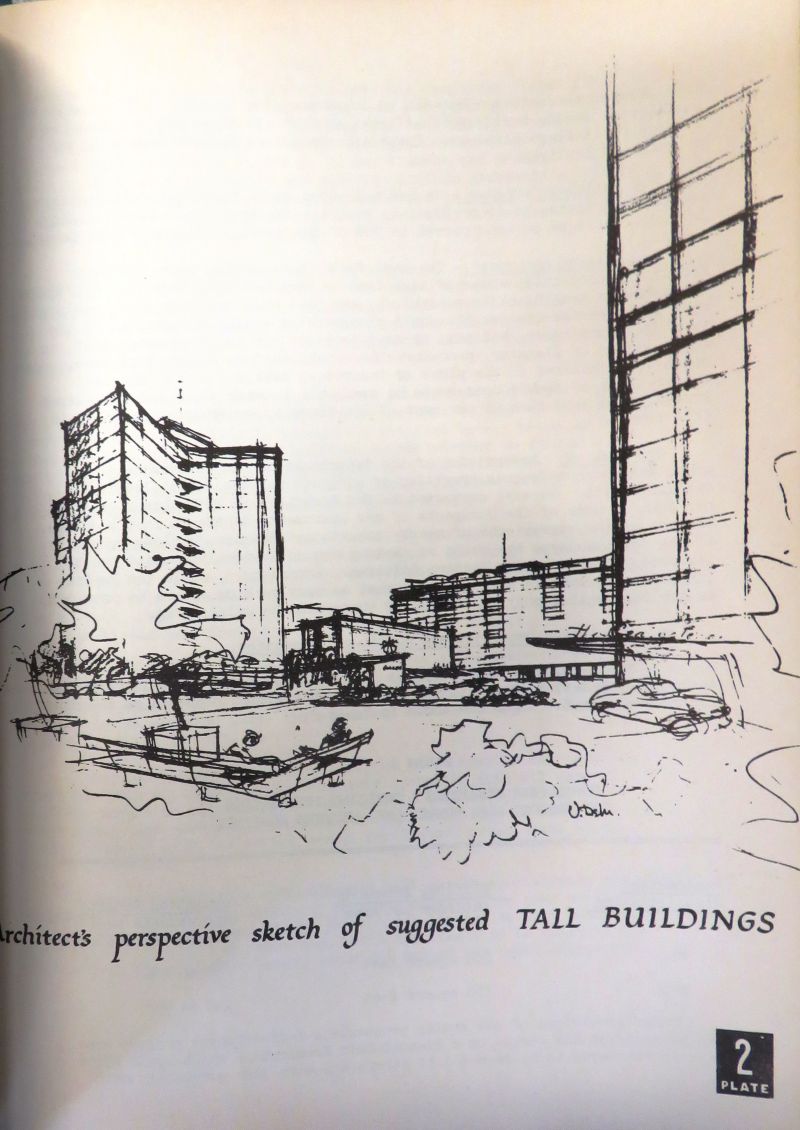

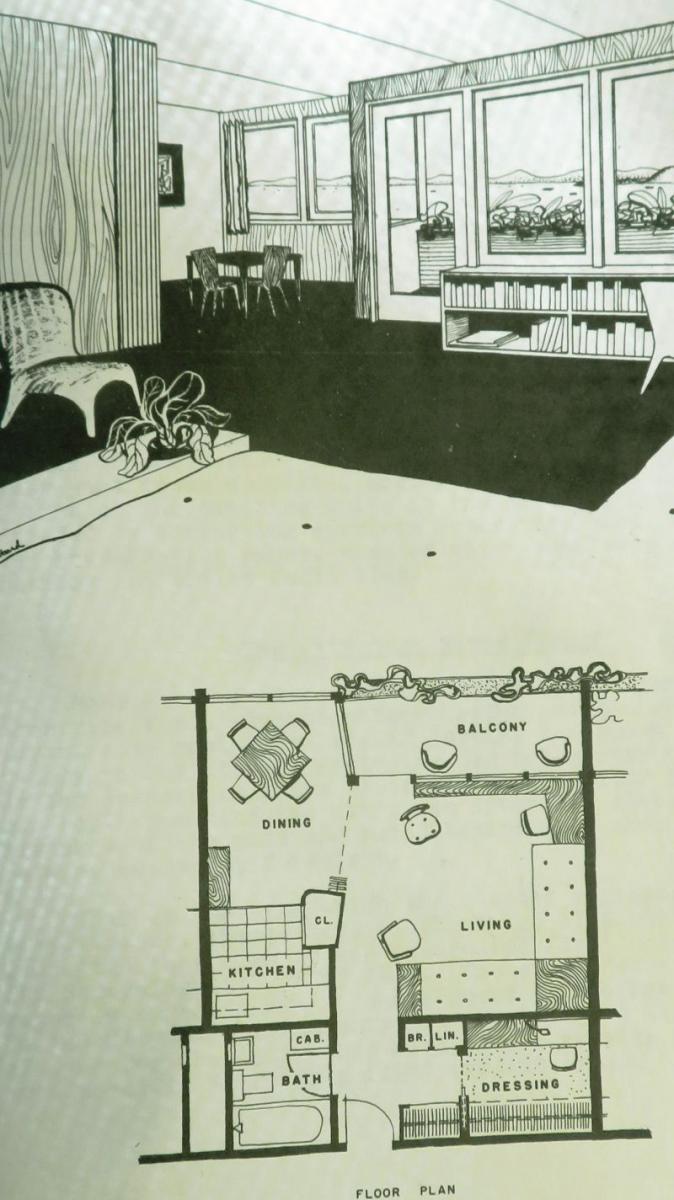

In the Western Addition Eichler built a highrise, 66 Cleary Court, and a group of townhomes, Laguna Heights, on land that had been cleared of Victorian-era and other older homes.

The area had been declared blighted for many reasons, including poverty, lack of open space, dilapidated buildings, and poor ventilation.

The question seems absurd at first. Joe Eichler, after all, was known as a liberal who famously sold his homes to all comers – white, black, Asian. Anyone.

|

|

|

But then, Herman too was a liberal, part of a movement of 'housers,' so called because they were socially conscious planners, architects, and advocates who sought more and better housing for all.

Also among their number were Eichler’s original architects, Bob Anshen and Steve Allen. Anshen essentially spoke on their behalf when he inveighed against the sort of city housing that Herman later tore down, and urged that it be replaced with more modern abodes.

“This is the great middle class, the pride and joy of America, living in slums,” Bob Anshen and his wife Eleanor wrote in 1944 in the winter issue of the progressive magazine TASK.

“This is probably where you are. You may not admit it. No one ever thinks of himself as living in a slum. He always thinks of himself as just happening to be living temporarily in a dark apartment because he can’t find anything else.”

Not even millionaires, he wrote, live in “as beautiful or as comfortable homes as our scientific achievements of today permit.”

Anshen and Allen, separately from Eichler, also took part in San Francisco redevelopment under Justin Herman. They contributed a grouping of homes to the Golden Gateway project near the Embarcadero, a project that was master planned by Wurster Bernardi and Emmons.

The Anshens’ words suggest just how strongly progressives felt about life in inner cities. The goal was to transform cities into something cleaner, with more air and light – something approaching the suburban ideal.

|

|

|

Redevelopment did produce much valuable housing, and Eichler’s communities in the Western Addition remain great places to live.

But as San Francisco’s Sun Reporter wrote in 1999, the process was deeply unfair and minorities were the victims:

“As Blacks were forced out of their homes,” the paper wrote on August 12, 1999, “many were only given $25 to $50 for moving expenses, and their homes went for as low as $11,500 because of the area's ‘limited visual merit.’ Home owners could not negotiate for higher prices. Some homes became parking lots, all in the name of a ‘greater government purpose’ for the Fillmore.”

Of course, attitudes change over time. Back in the 1950s and ‘60s, the focus was on improved housing, with less attention to the people who would be displaced. Also importantly, this was before environmental impact reports and public participation in planning issues became the norm.

By the late 1960s, however, the public was rising up – and Justin Herman was feeling the heat.

“Justin Herman has consistently ignored the plight of the poor people as he has moved from one redevelopment project to another,” Assemblyman John Burton argued, as quoted in the Sun Reporter on July 1, 1970.

|

|

|

But it’s worth remembering that Herman was widely admired nationally and in the city – and by many members of the minority community.

When Herman died of a heart attack in 1971, the Sun Reporter, an African-American-owned paper, wrote:

“After the severe community criticism by Blacks that [Western Addition] development was Black removal, Herman became interested and informed concerning the bases of racial minority protest.

“In the last few years he showed profound dedication to racial minority participation in redevelopment in the Western Addition, Hunters Point and Mission areas. While Herman irritated many a community-based redevelopment devotee with his forceful drive to get things accomplished, approximately three years ago he changed his approach from doing things for -- to doing things with -- racial minorities, and let community-based controversy find its common level before initiating the final decision-making process.”

While Eichler was eager to build in the Western Addition, it is clear that his motives – like Justin Herman's – were progressive, even idealistic, as he sought ways to provide housing for a range of people both in cities and suburbs.

How fair is it, really, to judge the decisions people made 50 years ago in light of today’s values, values that are ever changing?

Obie Bowman, the modern architect best known for his imaginative houses at The Sea Ranch in Sonoma County, mused about this in his thought-provoking blog:

“I suspect that 200 years from now many of our progeny will look back and wonder how we could have had some of the thoughts you and I accept today as perfectly normal. Perhaps herding animals for slaughter, fighting wars in the name of religion or philosophy … It’s pretty short sighted to judge the totality of someone’s life just because that life includes sins. It’s probably important, however, that the good of a life’s work outweighs the bad.”

- ‹ previous

- 527 of 677

- next ›