Blocks of Beauty - Page 2

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

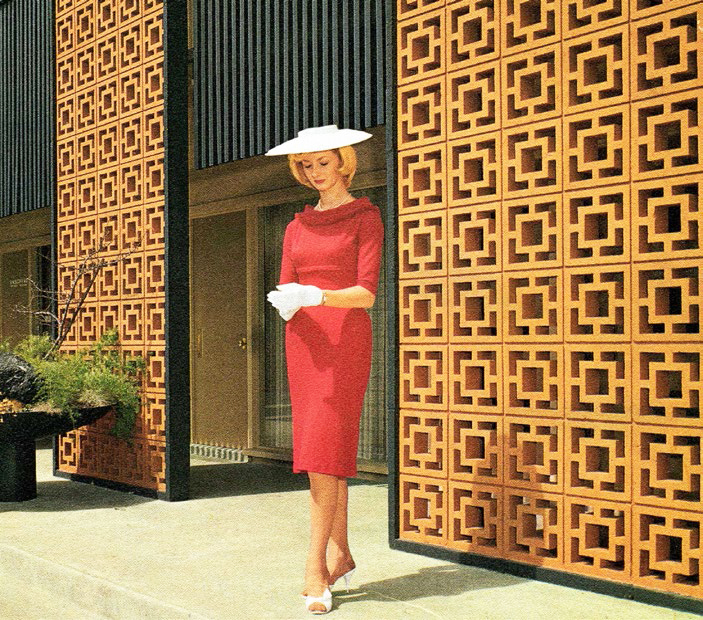

Decorative blocks also raise issues about high culture versus low culture—or, rather, high culture morphing into low culture.

The decorative block story begins, as so many mid-century modern stories do, with Frank Lloyd Wright. Wright's 'textile block' houses from the 1920s, including the Hollyhock House from 1920 in Los Angeles, today a museum house, used decoratively patterned, deeply textured blocks designed by Wright. The result were homes that seemed like Mayan temples while retaining the interior warmth that was a Wright trademark.

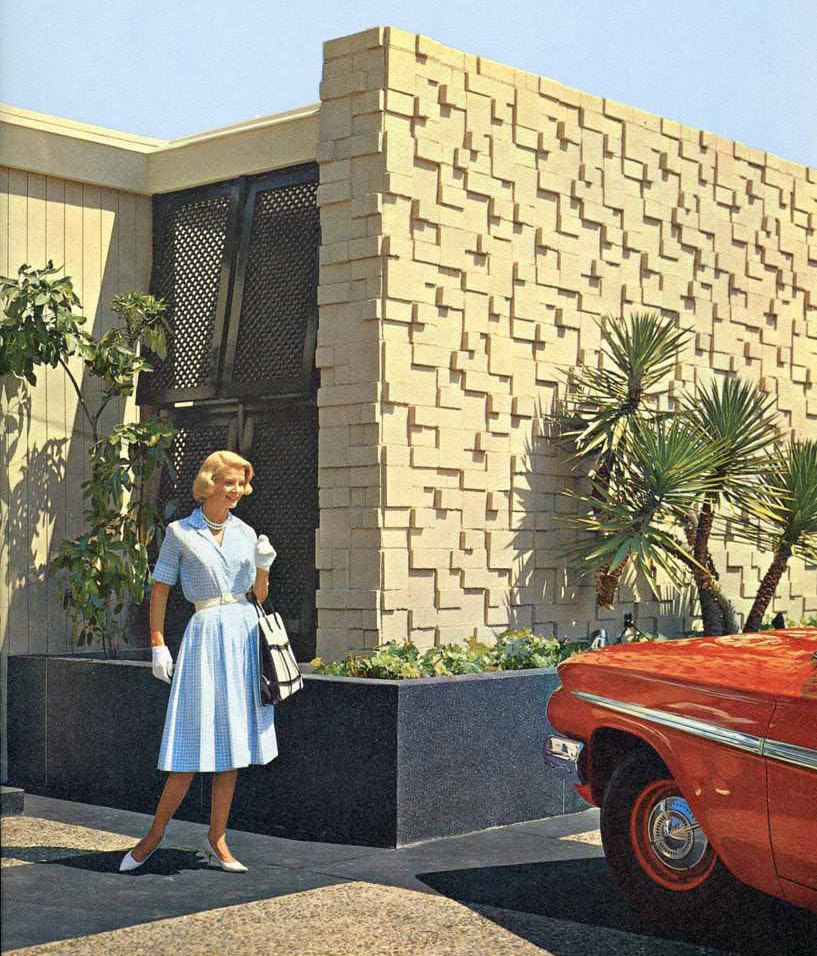

With his Oasis Hotel in 1924, Wright's son, Lloyd Wright, was probably the first to bring decorative block to Palm Springs, which 30 years later would become a showplace for screen and shadow block.

But decorative block didn't take off for another 30 years because the blocks were not commercially available. Also, 'cinder blocks,' as they were called, were considered fit for little more than foundations and industrial buildings.

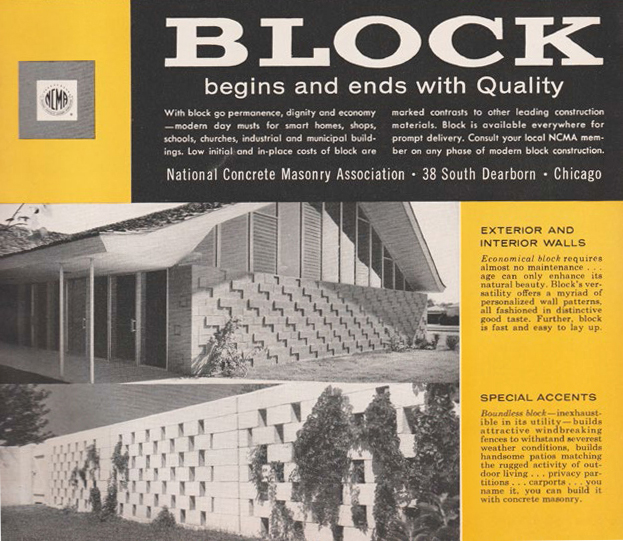

By the start of the '50s, though, there was something in the air—including aggressive marketing moves by the concrete block industry and the postwar migration of people to America's sun belt, which stretched from Florida through Arizona, and New Mexico to Los Angeles and San Diego.

"The concrete block is getting to be a big boy in the world of building," the Wall Street Journal reported in January 1953. At its convention, the National Concrete Masonry Association cited a 75 percent jump in block production since the end of World War II.

"Six years ago a 'cuber' [block-making machine] that turned out 600 blocks an hour was a top producer," the Journal reported of the technological advances behind production growth. "Today, one that can't turn out 1,000 an hour isn't worth buying."

The 1,500 block producers at the conference showed off glazed and colored blocks that were beautifying their product line—but if anyone talked about screen or shadow blocks, the Journal did not hear it. This suggests screen blocks were not yet available—nor desired.

But that same year an event got underway that would put the screen block on the map, big time. Famed architect Edward Durell Stone began designing a new U.S. Embassy in India. The building would be faced in screen block of Stone's design.

The idea of screened walls letting airflow and light into courtyards or interiors was not a new one—especially in tropical or desert climes.

But Stone's use of screen blocks, and his whole 'New Romanticism,' as his style of ornamented modernism came to be called, proved influential. In 1958, just after the embassy opened, Stone was cover boy on Time magazine, a high honor.

"It really exploded into the popular culture when the New Delhi embassy got a lot of press," says Ron Marshall, author with his wife, Barbara Marshall, of a new book, Concrete Screen Block: The Power of Pattern. It's published by the Palm Springs Preservation Foundation, in a town where the Marshalls are mainstays of mid-century modern appreciation.

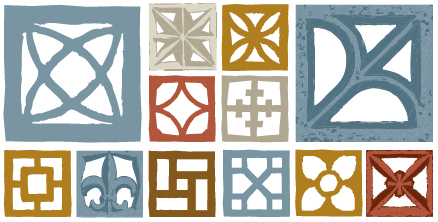

The Marshalls have focused on screen blocks, Ron says, because of their functionality, beauty, and variety of pattern. They spent ten years researching the book, producing as an appendix a 'screen block pattern guide,' of immense service to any true screen block watcher.

"It's amazing how many variations you can get from a 12-by-12 block, and how a simple pattern can be made into such a complex design [by setting blocks together]," Ron says.

"The deeper we bore," Ron says of their research, "the more fascinating it became."