Wexler's Palm Springs Steel

By the mid-1950s, steel houses seemed like a dream about to come true. Socially conscious architects, keen to provide well-designed, quickly built, and affordable housing for the booming postwar suburbs, focused on mass production. For many of them, that meant steel.

"It certainly lends itself to mass production better than wood does," says Bernard Perlin, an engineer with a California steel company at the time. "Your automobile and refrigerator and other appliances certainly prove that. It is a better material, stronger material. You don't have to worry about termites."

Architects, of course, were dreaming about more than steel's ability to resist bugs. Steel houses, prefabricated in the factory then erected on site in a day or two, would solve the housing crisis and turn the construction industry on its head.

A basic house, some reckoned, could sell for little more than a car. Carpenters, who worked in a craftsman tradition harking back to medieval days, would be replaced by an assembly line harking back to Henry Ford. Homebuyers would relish the convenience of living in a rationally arranged "machine for living," in the phrase invented by Le Corbusier.

No building material was as machine-like as steel -- not even reinforced concrete or plastics or plywood, which other architects dreamed about. Steel was poetic as well. Architects could devise elegant, sliver-thin profiles that allowed the house to dematerialize.

Few architects, it turned out, produced steel-frame houses for the masses. One of the few who did, Donald Wexler, saw steel not as a universal material but as something ideal for the only place he did business -- the desert.

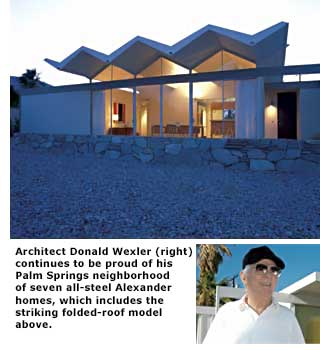

In the early 1960s, for the developers George and Robert Alexander, Wexler and his engineer, Perlin, designed a neighborhood of 38 flat- or folded-roofed all-steel homes at the edge of Palm Springs. Seven were built, and seven remain, a monument to a time that dreamed of steel, and pleasant places to live.

"I have to talk about the desert," Wexler says, in his matter-of-fact way, when asked recently about his vision for steel housing. "Steel, concrete, and glass are ideal materials for any building in the desert. They are inorganic, and they don't deteriorate in the extreme temperatures we have."

Unlike many so-called 'steel houses,' which are framed in steel but sided and roofed in other materials, the Wexler-Perlin models are all steel -- framing, roof, exterior siding. Only the interior siding is drywall. They use steel as a decorative as well as structural feature, exposed beams creating the home's look while revealing its structure, and allowing for a lightness that is almost ethereal.

"I don't think you could have had this thin a profile of wall if it was wood," says artist Jim Isermann, who lives in one of Wexler and Perlin's steel houses, built in 1962. "The walls are only three inches thick. There's so little between inside and outside.

Isermann's house is almost a single space wrapping around a core of bathroom, kitchen, and utilities. The core was assembled at the factory and trucked to the site. Steel wall and ceiling panels were also prefabricated. The house was assembled on site in a few days.

The main living air opens onto the backyard and pool through sliding glass. "Actually," Wexler says, "the houses are mostly glass."

There are drawbacks, Isermann says, though he loves the house and is one of Wexler's biggest fans. The house gets hot in the summer, and the steel retains the heat. Also, he says, "The steel makes noises as it expands." The first time he heard the banging, he thought the front door was slamming.

Isermann's house has a flat roof, so its look is classic, almost International Style. The roof next door is a series of jocular folds. Another house has a roof that pops up to provide clerestory windows. All have low garden walls of Utah green quartzite.

Wexler worked in Los Angeles for one of the modern progenitors of the steel house, Richard Neutra, who designed the steel-framed Lovell house in 1926.

Neutra didn't stick with steel as his primary material. But he inspired several younger architects to become steel enthusiasts. Several were called on by the Los Angeles-based 'Arts & Architecture' magazine for its program of Case Study houses, which ran from 1946 to the mid-'60s. The goal was to design modern, affordable homes that could serve as models for homebuilders everywhere. Eight Case Study houses used steel for framing, siding or both.

Architects who designed steel Case Study houses included Raphael Soriano, Charles and Ray Eames, Craig Ellwood, Pierre Koenig, and A. Quincy Jones of the firm Jones & Emmons, one of Joe Eichler's principal architects.

In 1954 Jones designed a house for his family from steel, which he appreciated for its economy and ease of use.