Film Profiles a Pioneering Black Architect

|

There are a lot of people who really love the work of Paul R. Williams, and who remember and loved the man himself. Some of them have gotten together both behind the camera and in front of it to make a charming tribute of a film ‘Hollywood’s Architect: The Paul R. Williams Story,’ which you can stream at your convenience.

Williams (1894-1980) had to be a tough guy to have succeeded in his world and at his time. He was an African-American who became an architect in the 1920s when the grand homes he designed were often sold with the restriction that they could not be sold to anyone not of the “Caucasion race.”

A teacher in high school tried to talk him out of the profession, saying, “Whoever heard of a Negro architect?”

|

No one. Williams was the first black to become a member of the American Institute of Architects, the first to become a prestigious fellow of the organization, and to first to win its gold medal, which he won posthumously.

The hour-long film, produced by PBS SoCal and RKR Media, is directed and produced by Royal Kennedy Rodgers and Kathy McCampbell-Vance. The film debuted last month at a red capet event in Los Angeles.

Karen E. Hudson, one of Williams’ grandchildren, was a force behind its production; she has worked tirelessly to keep his work before the public’s eyes for many years.

Though best known for his Period Revival mansions and somewhat smaller homes that were as elegant as the Hollywood stars ( Zasu Pitts, Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz, Bert Lahr) who inhabited them, Williams also became a modernist, as modern architecture became something to do in the 1940s.

|

A fair amount of it is shown in this movie. Though disappointing for fans of homebuilder Joe Eichler, no mention is made of the collaborative work Williams did with Eichler’s architect A. Quincy Jones. That included the Palm Springs Tennis Club and Town & Country Center.

(We do see a still images in the film that shows an unidentified Jones – but the narration suggests this is a photo of LA’s conservative elite. In fact, Jones was politically liberal.)

Maybe the filmmakers left out A. Q. Jones to avoid confusion with one of their talking heads, the musician Quincy Jones, who speaks movingly about Paul Williams’ effort to work as an architect despite racism. Williams learned to draw upside down, for example, so he could sketch houses while sitting across from a white client, rather than right up next to him.

Frank Sinatra, who had Williams design for him a house described in the press as “Japanese modern,” had no such concerns. Such projects for Hollywood stars brought much attention to William’s work. "Negro Architect Builds Sinatra Home,” one paper headlined.

|

The narrator tells us that Williams, a Republican who believed in self reliance, waged “a constant if quiet battle against the racism of the times.” By the 1960s, some Civil Rights leaders thought the architect did not go far enough.

Williams helped found a bank to lend to members of the African-American community and boost economic development. When it was destroyed by fire during riots following the Rodney King-police beating verdict in 1992, most of Williams’ architectural records went up in smoke.

(But not, fortunately, his drawings or plans, which were elsewhere.)

The 1930s and ‘40s was a time when a number of architects who worked in traditional styles opened up to modernism, often full throttle, sometimes to a degree. Williams falls into the latter category.

|

But, as with some other architects, you can see in his earlier, traditional work, an interest in moving towards what the European modernists were doing in the 1920s – not for ideological reasons, but because it seemed a better way for people to live.

His traditional houses have a charm and uniqueness about them, as some talking heads relay. Spiral stairs, curves, round windows, and cushy-looking columns were signature touches. They speak of comfort and ease.

He designed spaces that seem both indoors and outdoors, calling them ”garden porches.” Bob Iger, Disney’s chief, says of his home: “I love how [Williams] has integrated the exterior and the interior, that when you are in a room you feel as though you have a foot outside as well.”

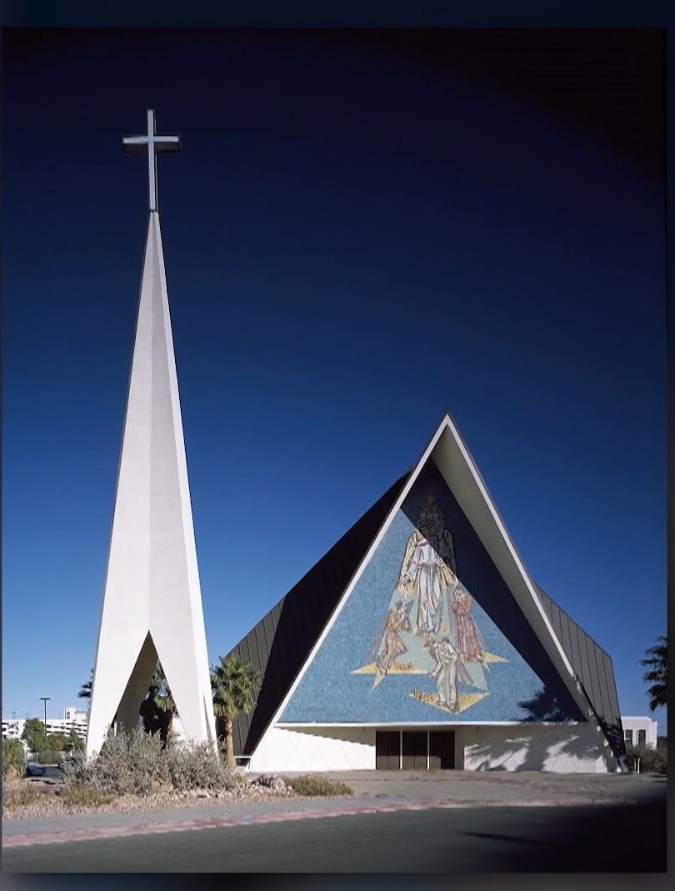

Designing in a modern style, Williams produced churches, office buildings, a hospital, the La Concha Motel in Las Vegas, even a small mid-century modern tract home development in Palos Verdes (which is not shown in this movie).

The film takes us into the home Williams designed for himself and his family at the start of the 1950s. It really sums up both the man and his work – a blend of traditional elegance, curves, some Streamline Moderne, and a lovely garden room. Just a charmer.

- ‹ previous

- 249 of 677

- next ›