Eichler Made History – by Losing a Lawsuit

|

|

|

Today, Joe Eichler is famous for building innovative, aesthetically pleasing modern tract homes for middle class clients. He is famous as well for selling his homes to all comers, minority buyers included – something few tract developers were doing in the 1950s.

But among some experts in tort law, particularly those who deal with homebuilding, home repairs, and other aspects of construction, Eichler is famous for something else as well. As a result of a lawsuit that he and Eichler Homes lost in 1959, the reach of product liability law was expanded to cover not just the sort of products you might have bought at the time at Sears or Capwell, but houses as well.

And since the Eichler suit opened the floodgates, the reach of product liability suits into the world of construction has expanded, then contracted a bit, then expanded again.

“That judgment held that Eichler, as a mass producer of homes, was liable - even if not negligent - for any defect in the manufacture of a product. Thanks to that precedent, California law now treats homes the same as televisions or computers in respect to liability. No other state applies such a standard,” writer Bill Lurz wrote back in 2000 in the magazine Professional Builder.

|

|

|

He added: “The ruling eventually unleashed a torrent of class-action construction defect lawsuits, filed by lawyers representing home owners associations, against builders, especially those active in attached and condominium development. The entry-level market, where higher densities helped to reduce unit prices, was hard hit.”

And the judgment is having reverberations to this day. As the lawyer Garret Murai has written recently, the notion of “strict liability” – that a builder could be responsible for an injury even if he was not negligent – is being applied now to contractors.

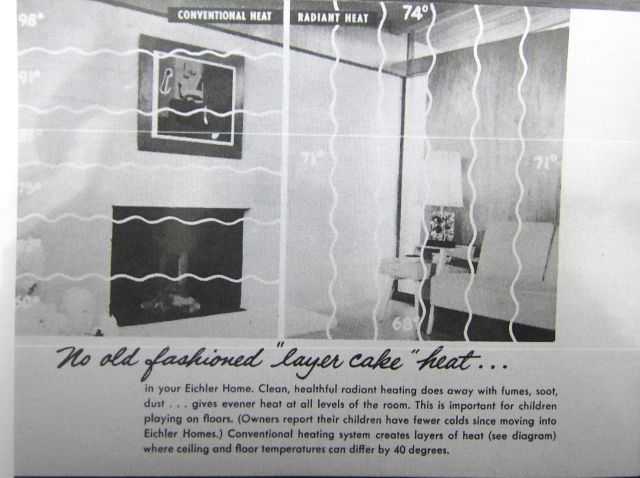

Among Eichler owners, radiant heat is both loved and despised – the latter by people whose steel tubing (installed when copper was not available) corroded.

It turns out, this radiant heat problem led to the first time ever in the US that product liability laws were applied to tract housing – a precedent-making decision that cost Eichler a little over $5,000 but remains in effect today. The ruling helped lead, one scholar says, to even broader application of product liability laws.

The tale is told, in rather dry terms, in a ruling by the California Court of Appeals issued January 29, 1969 – a decade after the pipes in the Palo Alto home of David Kriegler failed, and a whopping 18 years after they were installed.

|

|

|

“In April 1957 Kriegler purchased a home in Palo Alto that had been constructed by Eichler in the last quarter of 1951 and sold to Kriegler's predecessors, the Resings, in January 1952,” the judge in the case, Wakefield Taylor, wrote.

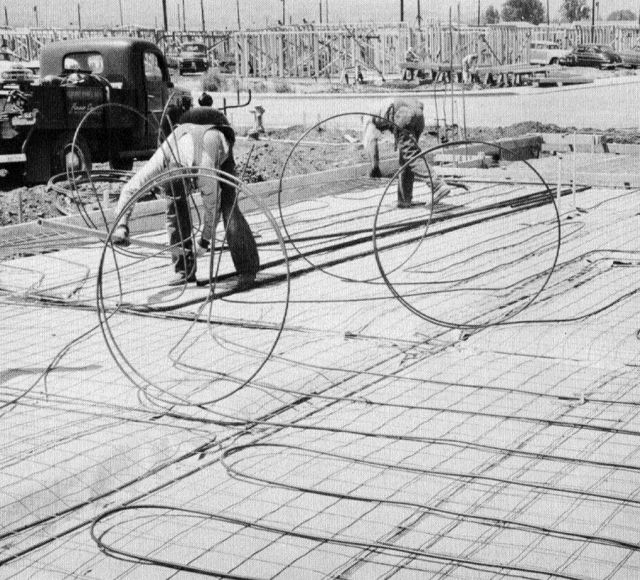

“Eichler employed Arro as the heating contractor. Because of a copper shortage caused by the Korean War, Arro obtained terne-coated steel tubing from General Motors. In the fall of 1951, Arro installed this steel tubing in the Kriegler home and guaranteed the radiant heating system in writing. Arro installed steel tubing radiant heating systems in at least 4,000 homes for Eichler.”

The radiant heating tubes failed due to corrosion in 1959. Kriegler called in Arro for repairs. The firm “concluded that the tubing was probably corroded throughout and replaced the entire heating system with a new one.”

Kriegler sued Eichler and his homebuilding firm, seeking just over $5,000. Eichler denied any fault, and sued both GM and Arro. The original trial judge ruled Eichler was liable to Kriegler in the above amount on the theory of strict liability because the radiant heating system, as installed, was defective.

“So far,” judge Taylor noted, when the came came to him on appeal, “[the strict liability standard] has been applied in this state only to manufacturers, retailers and suppliers of personal property and rejected as to sales of real estate.”

|

|

|

“Strict liability” means that someone – like Joe Eichler – can be found responsible for an injury even if he is not at fault or was not negligent.

In fact, Judge Taylor noted, the trial court did find negligence on the part of Eichler, citing the way in which the steel pipes were installed.

“The [trial] court found that at the time of the installation of the heating system in the Kriegler home, the building and construction industry had knowledge of methods whereby steel tubing could be used as a substitute for copper tubing with reasonable protection against corrosion.

"An essential element in such methods was the control positioning of the tubing well within the cement slab. Because of the susceptibility to the rust and corrosion in such steel tubing, it was good practice in the building and construction industry, both as to custom homes and tract developments, to take precautions to insure controlled and uniform positioning of the tubing well within the concrete slab.

"This was usually accomplished by other builders of custom and tract homes through the use of (1) double slab construction, (2) concrete blocks, or (3) wire clips. Eichler was negligent in not using any of these methods then known and used in the industry.”

But Taylor did not agree with the trial judge that Eichler had been shown to be negligent. In part this was because because Kriegler did not dispute Eichler’s denial of negligence. “We assume that the evidence is insufficient to support the findings concerning Eichler's negligence in the installation of the heating system,” Taylor wrote.

But he found Eichler liable even without negligence -- and that is why the lawsuit became part of history.

- ‹ previous

- 182 of 677

- next ›