Going Modern by Delving into the Past

|

|

|

It’s an exhibit that is mostly black, gray, and white, with a few splashes of turquoise, rose, and gleaming aluminum.

But the Asian Art Museum’s current examination of one artist you may think you know paired with another you have probably never heard of tells a compelling tale about two artists from two countries united by their desire to keep what was best in traditional Japanese art while creating art that was both modern and was serving “some purposeful social end.”

'Changing and Unchanging Things: Noguchi and Hasegawa in Postwar Japan,' on view through December 8, offers much visual pleasure despite its austere tonality. The show focuses primarily on work from the 1950s and emphasizes how the two artists influenced each other in a desire to be modern while evolving from Japanese tradition.

“The exhibition is organized around a series of themes that bring out the resonances between [Isamu] Noguchi’s sculptures and design work and [Saburo] Hasegawa’s explorations in painting, printmaking and photography,” the museum states. “Situating the work of both artists side by side forcefully reveals their innovative fusion of Japanese tradition and modernist form and shared aesthetic sensibilities.”

|

|

|

Noguchi (1904–1988), best known to many owners of mid-century modern homes for his sleek freeform tables, is admired for the variety of his work, and for the variety of textures and tones within each work.

Saburo Hasegawa, born in 1906 and passed on from cancer in 1957, stopped painting in a European style at the end of the 1940s to work primarily in traditional Japanese sumi ink. The museum says the exhibit is the “first substantial consideration of Hasegawa’s work outside Japan."

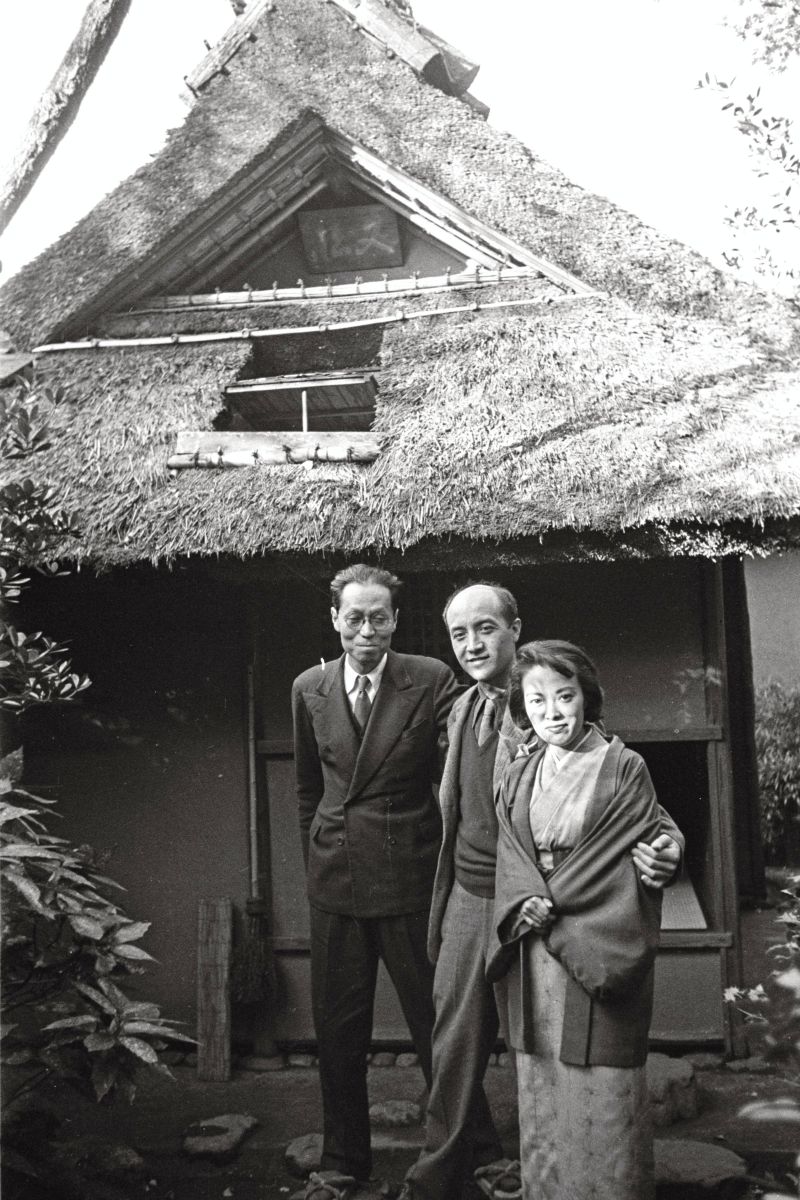

The artists met in 1950 when Noguchi, an internationally known American artist, visited Japan and Hasegawa was engaged to be his guide. One place that impressed Noguchi was what the catalog describes as a “tiny mud-walled teahouse from the sixteenth century” designed by the legendary Rikyu.

“Noguchi was spellbound by these encounters with the treasures of Japan’s past,” Bert Winther-Tamaki writes.

It was during this trip, Naoaki Nakamura writes in the catalog, that Noguchi gave a talk about “art and community.”

“Noguchi argued that it was now necessary to bring art out of the realm of the purely individual and restore connections between art and society by integrating fields such as sculpture and architecture,” Nakamura writes. “He called on artists to recognize Japan’s intrinsic ‘uathenticity and originality’ -- specifically, what Noguchi referred to as ‘the modern’ -- so as to prevent a loss of Japanese identity under the influence of foreign countries.”

|

|

|

Noguchi and Hasegawa quickly became friends and influenced each other’s work as they explored how traditional Japanese art could become modern – while retaining tradition.

Neither artist could be considered traditionally Japanese in their cultural backgrounds. Noguchi was born in America to a Japanese father and Caucasian American mother. He lived part of his boyhood in Japan before returning to New York, where he achieved success as both artist and designer.

Hasegawa grew up in Japan in a Western-styled home where English was the second language; his dad, a banker, had worked in London and Hong Kong, where Hasegawa lived for part of his childhood. Hasegawa’s first wife was British.

In 1955 Hasegawa moved to the Bay Area, where he found better reception for his work than in Japan. There he taught at the California College of Arts and Crafts, wrote, continued to create art, and became friends with the writer and Zen popularizer Alan Watts.

Watts’ houseboat in Sausalito was the center of an artists and writers’ scene that attracted Joe Eichler’s architect Bob Anshen, who likely met Hasegawa there or at one of the artist’s popular lectures.

Japanese design influenced Eichler’s architects deeply. Anshen and his partner, Steve Allen, had traveled in Japan shortly before World War II, and A. Quincy Jones spoke of the influence of Japanese design in his work, harking back to his childhood friendship with the family of Japanese-American gardeners.

On display in the two large first-floor special exhibit galleries are Noguchi sculptures in aluminum with folded plates, terra cotta suggesting ancient Haniwa sculptures from Japan, iron pots that subvert their original functions, granite monoliths – one in the shape of a foot, and more.

|

|

|

The influence of ancient and traditional Japanese art is far from the only influence to be seen in the work of both men in this show. Picasso, the Surrealism of Joan Miro and others, even Russian Constructivism can be seen in Noguchi’s work.

One telling work is ‘Fence,’ from 1952, a tabletop sculpture of terra cotta that suggests linked living forms in a kind of mid-century modern screen. His standing statue ‘Bird Song’ harks back to the avian alter ego of the earlier Surrealist artist Max Ernst.

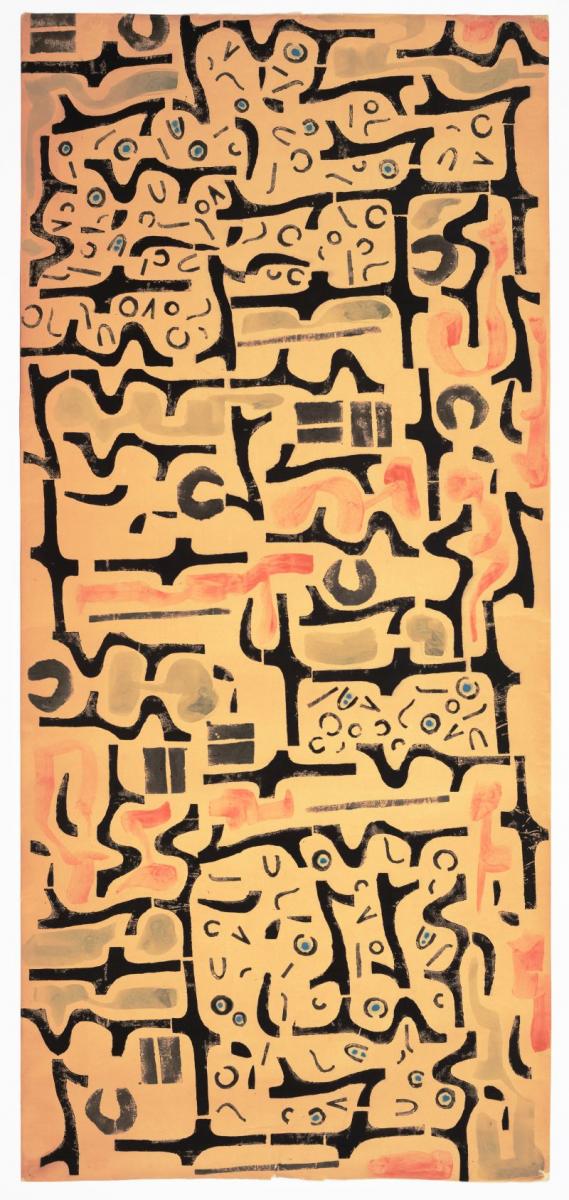

Hasegawa’s work too blends the verve of Japanese calligraphy with modern European influences in a lively way. Rubbings to bring out the texture of wood suggest Surrealist frottage, and a calligraphic drawing of a nude from 1956 suggests Picasso – and even the New Yorker cartoonist Saul Steinberg.

Both men, who were both pacifists, had been deeply influenced by the recent war between their two countries. Hasegawa sat it out quietly by focusing on the tea ceremony and other traditional arts, eschewing art for the time.

In the States, Noguchi was not forcibly interned, as were so many Japanese-Americans. But he voluntarily spent about a year in a camp, in solidarity with others.

On display are some of his models for gardens and other architectural projects, including one that was never constructed – a bell tower for Hiroshima to serve as a memorial for the dead.

- ‹ previous

- 277 of 677

- next ›