Great Landscaping Adds Historic Value

|

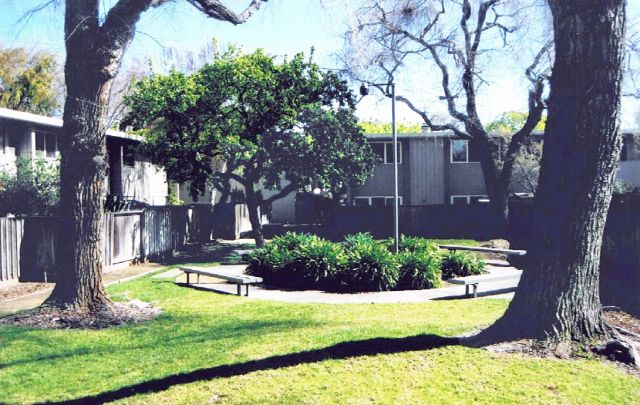

With its canopy of 300 trees, shaded pathways and enclosed courts, and four-foot roof overhangs, the neighborhood of Pomeroy Green “is noticeably cooler” than neighboring homes, Ken Kratz writes in a nomination that, if successful, would make the cluster of cooperative homes only the fourth Eichler tract to be named to the National Register of Historic Places.

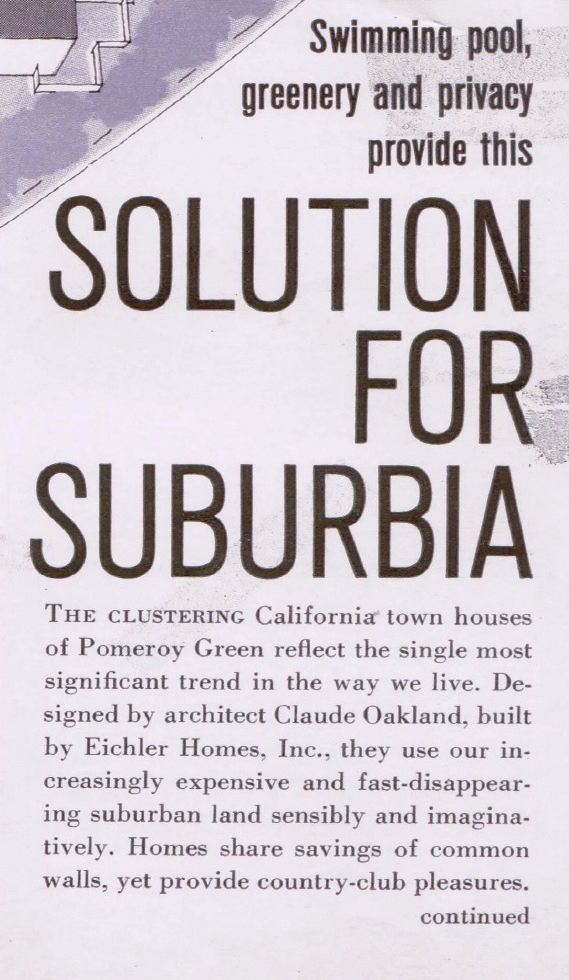

And it would be the first Eichler development that is not made up of single-family homes to be so honored.

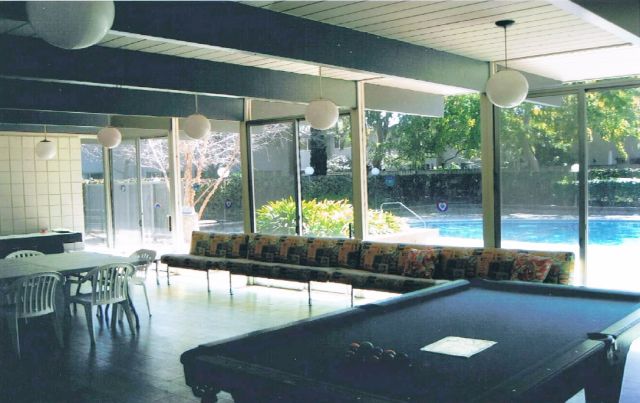

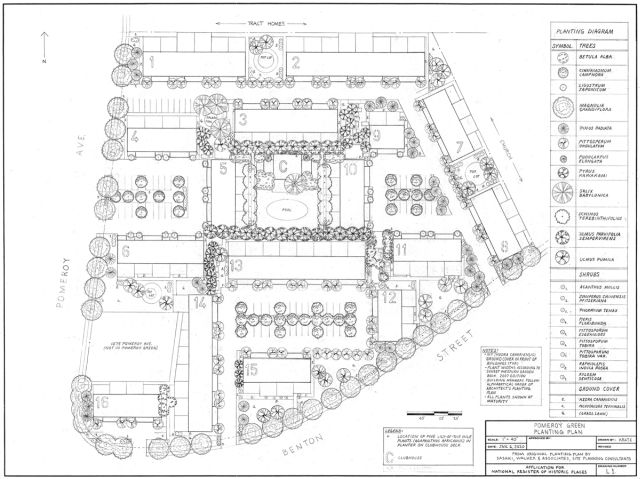

That might be why Kratz puts so much emphasis on the landscape design for the 78-townhouse complex, which arrays 17 buildings (one is a clubhouse) on seven acres and opened in 1961, a pioneering example of cooperative living in California. Each townhome is two stories, with a garage below, and with enclosed front and back yards.

|

(Pomeroy West, a similar but larger townhouse community by Eichler, opened across the street two years later, but is not part of the Register effort.)

In few of his tracts did Eichler’s architects work as closely as in the Pomeroys with landscape architects. Here the work of architect Claude Oakland is entirely integrated with that of Sasaki Walker and Associates, a modernist firm whose principals, Hideo Sasaki and Peter Walker, soon emerged as giants in their field.

The firm was brand new when Eichler hired it in 1961, having been founded two years earlier.

|

“The building architecture and landscape architecture are integrated at Pomeroy Green in order to create a coherent spatial organization that provides community, privacy, fresh air circulation, and control and use of daylight,” Kratz writes in the nomination, which will be posted soon on the website of the state’s Historic Preservation Commission, which will consider the matter, likely at its November 6 meeting.

In general, for a neighborhood to be named to the National Register, more than half of the residents must approve. Ken has not polled residents, but has kept neighbors informed throughout the process. Notices will be sent by the state to all residents, who will be able to weigh in with letters of support or opposition, and to speak at the meeting online.

Jay Correia, a historian who staffs the commission, notes that being on the National Register imposes no restrictions. “All land use authority resides with the local government,” he says. “We hope the local government provides design review [of historic properties], but we have no say in the matter.”

|

Historic designation – the site would also be on the California state register – would make possible use of the state Mills Act, which could provide property tax relief.

“Making it eligible for the Mills Act would allow us to reduce our property tax and save money that could be used to maintain Pomeroy Green,” Ken says.

As he has worked on the nomination, Ken has become immersed in the development of modern landscape and site planning design. He ties Pomeroy Green’s design to the tradition of the Garden City Movement, and cites earlier examples from California, including Rudolph Schindler’s Pueblo Ribera Apartments in San Diego. Ken even cadged an interview with Peter Walker.

|

Ken discusses how the design for Pomeroy Green qualifies as modern:

“The landscape design is simple, having few species of plants, is efficient, having low-maintenance plants, and defines space, repeating a variety of plants along and around pathways, buildings, and other architectural features.

“The buildings themselves echo this space-defining characteristic of the landscape design by forming a variety of well-defined spaces that are further enhanced by the plantings, such as the long driveways, courts, and green open spaces.”

Pathways allow most residents to get to the pool, play and sitting areas without crossing roadways. The design separates autos from people.

Use of tree species unifies the look, while providing shade and setting off the community from the nearby streets and traffic noise, Ken writes.

|

“The selection of magnolia trees (Magnolia grandiflora) along Pomeroy Avenue and Benton Street, for example, provides a simple and efficient form in addition to being highly functional,” Ken writes.

The nomination makes clear that while some plant species have changed over time, and there have been some modifications in uses of the landscaping, both the landscaping and buildings remain essentially intact.

Ken writes:

“The architecture of Pomeroy Green conveys the feeling of the early 1960s, a time when people were exuberant about all things modern, including electronics, television, outer space, automobile culture, and leisure and recreational activities.

“The modern design of the complex, with buildings featuring crisp rectangular-shaped forms that contrast with the organic shapes of the trees, is visually striking. The complex still exudes a sense of modernism due to its regularity of repeated forms and repeated building components, its lack of architectural ornamentation, and the straightforward use of materials.”

- ‹ previous

- 283 of 677

- next ›