Eichler Co-op Aims for National Register

|

|

|

Will one of Joe Eichler’s most unusual neighborhoods become only the third Eichler tract to be honored by placement on the National Register of Historic Places?

A betting man would say yes.

Reading through a draft version of the National Register nomination for the neighborhood Pomeroy Green, a 78-home cooperatively run townhouse community in Santa Clara, the reader comes away with one conclusion.

Make that two.

One. Pomeroy Green, which opened in 1963, is a largely intact and historically important place, significant for its role in the development of cluster housing, and for its association “with the lives of persons significant in our past” (that would be Joe, his son Ned, and the architects and landscape architects behind the plan), as well as other reasons.

And, two: That the author of this nomination, Ken Kratz, a resident of the complex, a professional building inspector with an eye for detail, is one thorough and hard-working guy.

|

|

|

Since 2005, when an entire committee of Eichler-philes managed to place two Palo Alto tracts on the Register, with the hope that other tracts would follow, no one else has managed to mount a credible campaign – until now.

(Several other nominations are in the works, including in the city of Orange. Folks across the street from Pomeroy Green, in Pomeroy West, are also considering such a move.)

Reading through Ken’s nomination suggests how much work is required. But the document does make a compelling case. He is revising the document following a critique from a state historian with the Office of Historic Preservation.

“All the content is there,” Ken says of the nomination. “It just has to be reconfigured” to increase clarity. He expects the nomination to go before the State Historic Resources Commission in 2019. State approval is almost always followed by quick federal approval.

The draft nomination, 40-plus pages plus photos and maps, argues that Pomeroy Green is nationally significant.

|

|

|

Summarizing its significance, Kratz writes:

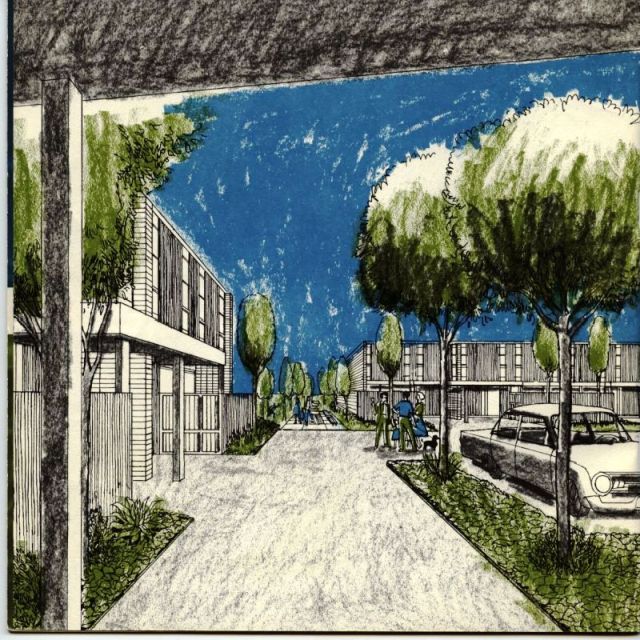

“It is a masterwork of a collaboration between the merchant builder Joseph Eichler, the architect Claude Oakland, and the landscape architecture firm of Sasaki, Walker and Associates. Due to its position in the history of the development of the City and the surrounding cities of Santa Clara County, popularly known as ‘Silicon Valley,’ the complex reflects local and national trends in suburbanization, particularity suburbanization characterized by proximity to metropolitan expressways and dependence on the automobile as the primary source of transportation.

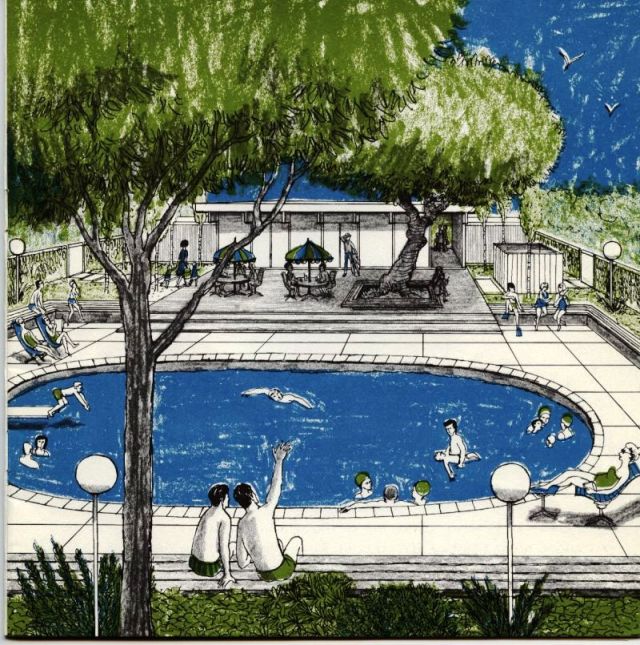

“Pomeroy Green is a project that is the realization of the goals and ideals of a post World War II merchant builder; Eichler was selling a lifestyle as well as a home. Pomeroy Green meets criterion C because it is significant in community planning and development; it is an early example of cluster housing that features common grounds, social spaces and cooperative management of the complex by the residents.

“Pomeroy Green's clustered multi-family housing challenged the prevailing pattern of suburban development that dominated the middle-class housing market in the U.S., namely the single-family tract home.”

|

|

|

“Pomeroy Green is so early in the development of cluster housing that its design was the inspiration for a brochure, published in 1962 by the Santa Clara County Planning Commission, on a new type of housing development, the cluster subdivision,” Ken writes.

“Pomeroy Green…was featured in many national publications at the time of its completion. The complex was featured in a book, ‘Cluster Development,’ by William Wythe, a famous journalist.

“The July 14, 1964 issue of Look magazine, a popular photo journal of its day that was distributed nationwide, featured a seven page photo article on Pomeroy Green. The article, 'Solution for Suburbia.' takes a photographic look at the advantages of cluster housing. The article includes pictures of the centrally located kitchen and the two fenced yards where children can be watched as the housewife works in the kitchen.”

The level of detail provided in the nomination is astounding. “The complex has historic integrity because only small changes have been made to its building design, landscape, and building materials,” Kratz writes.

But he then goes on for several pages mentioning every change that ever occurred in color, window material, and shape, even changes in playground equipment and path makeup.

Just to be honest.

|

|

|

Kratz rightfully makes much of the integrated planning that took place between architect Claude Oakland and landscape architects Sasaki Walker.

“Overall,” he writes, “the project feels spacious due to the careful clustering of the buildings that allows open space to prevail between buildings.”

Kratz also emphasizes the importance of Joe and his son Ned to non-discrimination in housing, citing Eichler Homes’ policy of selling homes to all and Joe’s testimony before Congress on open housing, among other things.

“Their activities helped in the eventual passage of the 1968 Civil Rights Act, when fair housing became law throughout the United States,” Kratz writes. “The period of significance for the Pomeroy Green Residential Historic District is from 1961, the date Pomeroy Green project was announced in the Eichler Homes annual report, to 1968, the date of the passage of the Civil Rights Act. Pomeroy Green has local, state, and national significance.”

Kratz says some or all of this argument may be dropped, as the state historian did not think that Pomeroy Green sufficiently spoke to this aspect of Eichler Homes' policies.

Nominations for the National Register are supposed to be straightforward and fact filled, not emotion-laden missives. But at times emotion sneaks through – as well as a sense of pride that comes from living in a well designed and well tended community.

“Walking around Pomeroy Green makes one feel as though one is back in the early 1960s, a time when people were exuberant about all things modern: electronics, outer space, automobile culture, and leisure and recreational activities, to name a few,” Kratz writes.

“Pomeroy Green's modern architecture, like all modern architecture,” he writes, “uplifts the viewer due to its straightforward use of materials in striking arrangements in the service of sheltering and accommodating the life of the residents.”

|

|

|

- ‹ previous

- 166 of 677

- next ›