How Women Helped Design Eichler Homes

|

|

|

They may have been designed and built by men, the Eichler homes so many of us love, but they were designed in large part for women, kitchens designed to provide views of children at play, built-in appliances provided to ease housework. But were these homes really women’s prisons?

That’s what some mid-century critics of suburbia argued in the early 1960s, starting with social critic and feminist Betty Friedan, who asked in her 1963 book ‘The Feminine Mystique,’ “But is her house in reality a comfortable concentration camp? Have not women who live in the image of the feminine mystique trapped themselves within the narrow walls of their homes?” Friedan was referring to suburban houses in general.

Friedan’s quote comes from an essay that recently came to the attention of Eichler Network. ‘The Eichler Home: Intention and Experience in Postwar Suburbia,’ by Annmarie Adams, who disagrees with it – to a large degree.

But if the Eichler home was not a prison, she suggests, that was due less to the architects behind the homes than to the women who inhabited them.

|

|

|

“Suburbia was an arena in which women fought back,” Adams wrote in this essay from 1995. “Isolated in their houses, women expressed their own ideas about making space, often originating in dissatisfaction, and contested male power in architectural terms.”

She did credit the designers of Eichler homes with this important accomplishment though – creating the best place in America for moms to bond with their children a la the fashionable theories of Dr. Benjamin Spock.

“The ideal space for Spock-style mothering was the atrium in the Eichler house,” Adams wrote.

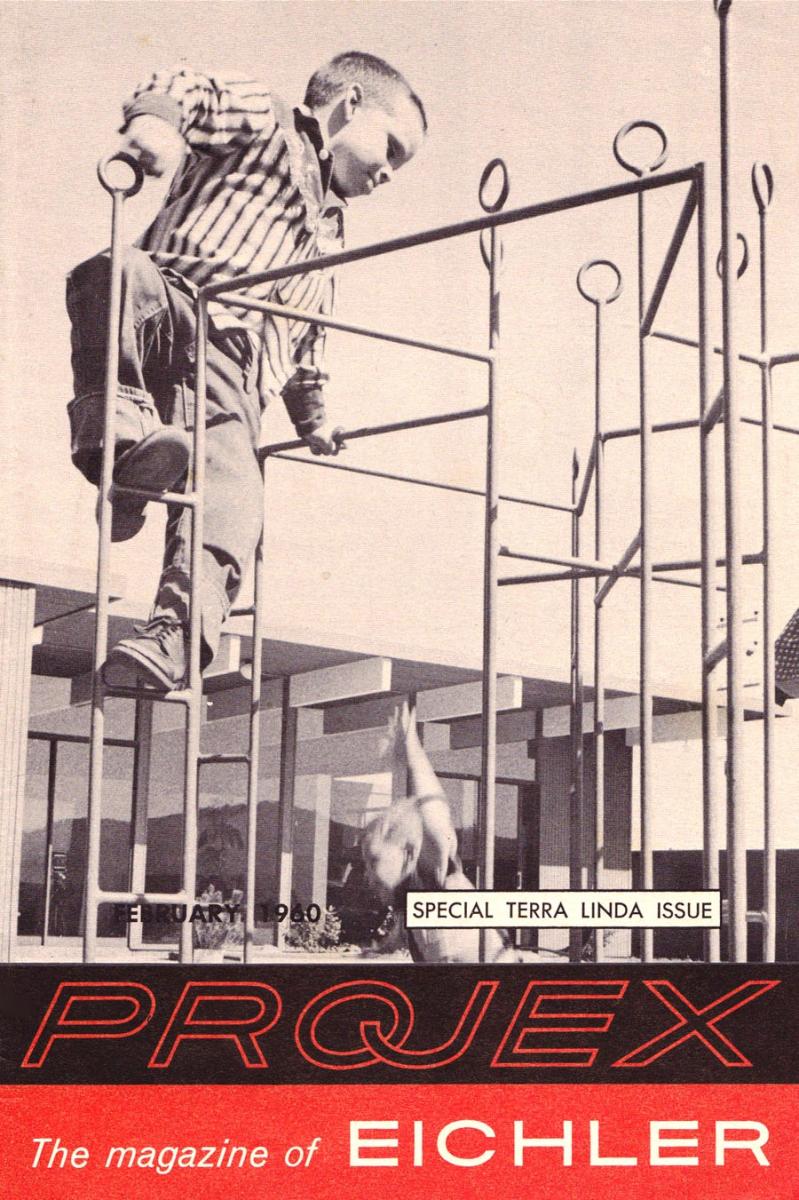

Adams today is director of the architecture school at McGill University in Montreal, and a writer who focuses on the architecture of health care. Twenty years ago she was a member of the faculty at McGill who got in touch with a family who moved to the Eichler subdivision in Terra Linda in 1961.

The “Clarksons” – she kept their real names secret – were expecting their fourth child when they bought their Eichler. At the time of the essay’s writing, they still lived in the house, and had left it largely unchanged.

The design of the home, the design of the community in which the home fit, and the separation of suburbia from the wider world, represented a “deliberate construction of social relations,” Adams writes. Fences cutting off yards from view, and the blank wall facing the street, hindered social relations between women who were neighbors.

“The house itself also acted as an impenetrable wall, reinforcing the larger gesture of withdrawal and isolation expressed in both the peripheral location of Terra Linda and in its site planning,” Adams writes.

“In contrast to the street-facing orientation of traditional American houses, family life was directed to the back of the lot in the Eichler home. In an effort to ‘protect’ mothers and children, Eichler had actually surrounded the family with architecture.”

|

|

|

In Friedan’s view, post-war suburbia cut off women from all social, political and workplace contacts, creating – yes – desperate housewives.

By talking to the ‘Clarksons,’ Adams discovered ways in which the mom of the family, and her kids as well, evaded these prison walls.

“…Joan Clarkson and her children did not simply follow blindly the architectural instructions spelled out by their house. They assumed active roles in the ‘construction’ of their own spaces, contesting many of the relationships presumed by the house.”

No, Joan and her kids didn’t redesign the house. But how they used the house and its surrounding space, Adams argues, is as much a part of architectural history as the work of Eichler’s architects, even though “it exists in behavior rather than in built fact.”

This suggests, perhaps, that Ernie Braun’s famous promotional Eichler Homes photos, that show how people in Eichlers were expected to act, and David Toerge’s photos for Eichler Network’s CA Modern magazine, showing how people really do act in the homes, are important historical documents worthy of further study.

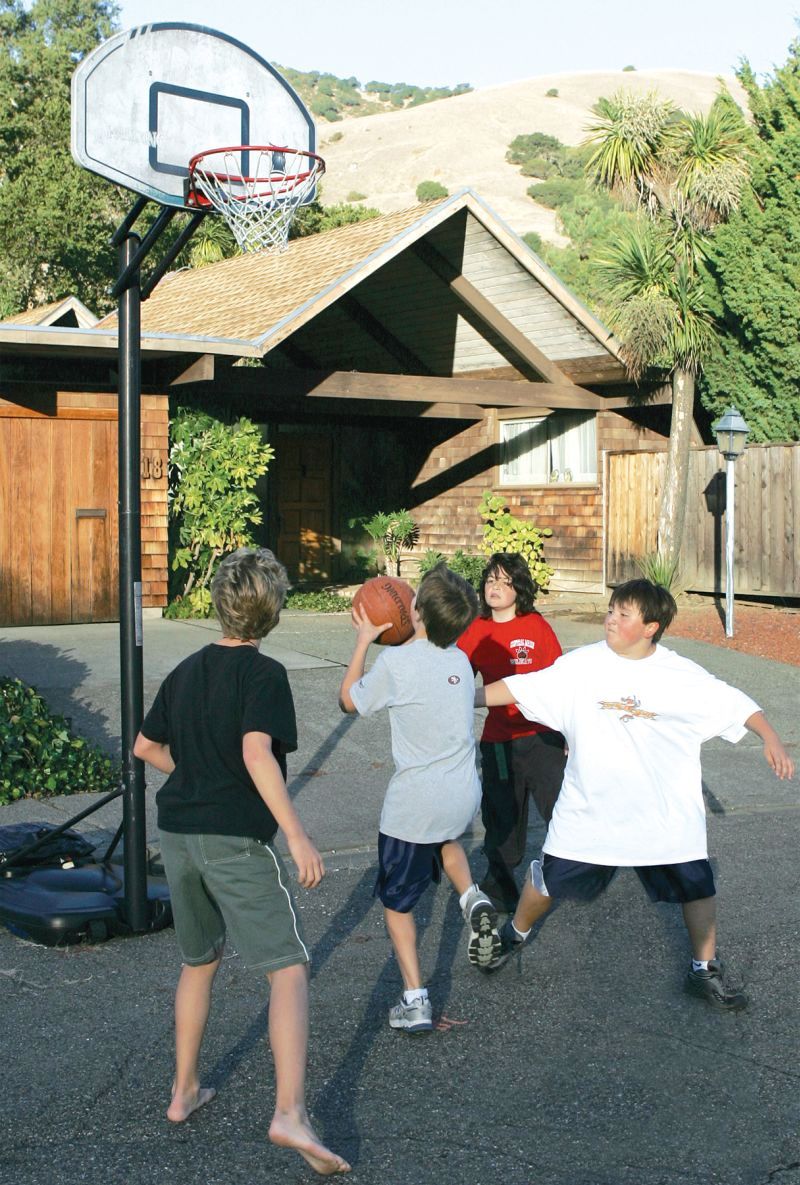

How did the Clarksons ‘subvert’ the Eichler design? In ways all Eichler owners will recognize. Rather than staying cooped up in private yards, the kids played kickball with neighbors every night in the street.

|

|

|

They turned the garage into a full-time game room, complete with a hopscotch board marked on the concrete. The kids also played in the side yards, private areas not under the view of their mom. Though this, it seems clear, always had been part of the Eichler plan.

The kids also dug holes beneath backyard fences to visit friends – something we at Eichler Network have seen happen in several Eichler neighborhoods.

Concern for privacy also caused the Clarksons to subvert the openness of their Eichler by keeping the master bedroom shades tightly drawn much of the time. They also turned their family multi-purpose room into more of a formal dining area.

Although ‘Joan Clarkson’ did not form close friendships with her neighboring moms, she avoided the blight of suburban isolation by befriending women she met while her kids swam at the public pool and by working on fundraising with the active Summer Hills Club.

In fact, as countless visits by Eichler Network to Eichler neighborhoods suggest, women have made impacts on their homes and their neighborhood and on life within both in significant ways never suggested by Adams’ essay. Her essay was, after all, based on the experience of a single family.

By renovating and redesigning spaces, choosing furnishings, creating areas for children to play; by building friendships, creating community organizations, forming cooperative daycare arrangements, building neighborhood parks, advocating for social change both within their neighborhoods and in the wider community, the women who have lived in Eichler homes have done more to make them work than the men who designed them in the first place.

|

|

|

- ‹ previous

- 339 of 677

- next ›