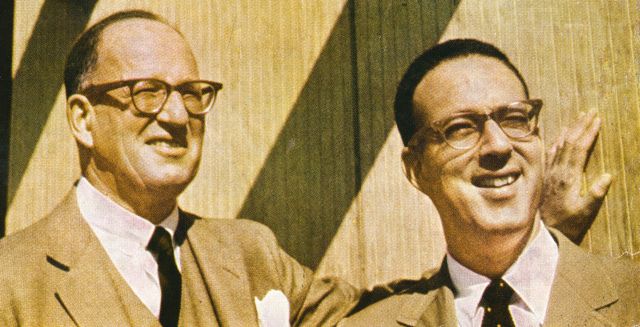

Were Joe and Ned Eichler Crusaders?

|

|

|

It’s fairly well known among people who appreciate mid-century modern Eichler Homes that the company sold its homes to people of all ethnic backgrounds, back before fair housing laws outlawed discrimination.

But did you know that Joe and son Ned, who has said he was the one who “instigated and managed Eichler Homes’ policy of selling to blacks,” played an even more significant role in furthering fair housing for all -- by working behind the scenes?

Probably not. As Ocean Howell, a professor at the University of Oregon, writes, “The Eichlers are known for their role in bringing architectural modernism to the masses, but scholars have almost completely overlooked the Eichlers’ civil rights activism.”

Howell’s article, ‘The Merchant Crusaders: Eichler Homes and Fair Housing, 1949-1974,’ published in the Pacific Historical Review, can be read online, for a fee.

He makes the point that, while selling to Asians and African Americans helped many individual homebuyers, the Eichlers achieved much broader impact by testifying at hearings and, on Ned’s part, by serving as chair of a state housing commission whose work led to fair housing legislation.

For example, Joe Eichler testified before the U.S. Civil Rights Commission in 1960, speaking as a successful builder whose career proved that open housing could be part of a profit-making business.

|

|

|

The housing commission was created in the early 1960s by California Governor Pat Brown, whom Joe had gotten to know from his political involvement with the Democratic Party. Ned got to know him too.

“One Sunday afternoon in 1957, when I was swimming at my fatherʼs house,” Ned wrote in an unpublished memoir, “Pat surprised me by asking if I thought he should run for governor,” Ned has written. “I replied that from what I knew of the matter, which was not much, he probably should. He did run and won handily.”

“From that position [of chair],” Howell writes, “Ned did more than any other individual to shape the state’s housing policies, including crafting and promoting California’s fair housing law.”

By selling to minorities while running a profitable housing business, Eichler Homes also dispelled the lie promulgated by other developers and by builders associations that fair housing would not work in a free market.

“Eichler Homes demonstrated that housing could be integrated without fundamentally altering the character of the suburbs, instigating battles with municipalities, or hurting the bottom line,” Howell writes.

He contrasts Eichler Homes, in this regard, from some other developers who were described at the time as “crusaders” who “insisted on selling homes on an open-occupancy basis” but, unlike Eichler Homes, “typically operated at a loss.” Their goal was social betterment, not running a business.

Thus these developers had little impact on the housing market overall and suggested rather that “that profit and social progress were at odds.”

Howell has coined the term “merchant crusaders” to refer to builders whose goal was to make a profit while also selling to all and engaging in “civil rights activism behind the scenes.” Howell focuses on Eichler Homes, while saying that “preliminary research” suggests that other builders did this too.

|

|

|

Howell runs down the history of Eichler’s open housing policy: from selling to Asians in the early days of the company, to selling their first home at the start of the 1950s to a black buyer. This black man was a civil rights activist named Franklin Williams, a lawyer for the local NAACP who later became the state’s assistant attorney general.

Interestingly enough, when Joe Eichler built the first home for Williams it was a standalone in Palo Alto – not within an Eichler subdivision. Williams later said he would have preferred a subdivision house, but was told the tract was sold out even though it wasn’t.

The dramatic tale of Joe Eichler and Franklin Williams is a highlight of Howell’s paper, suggesting how Joe moved from a liberal who wanted to do the right thing but thought it might hurt his business to a man who spoke out loudly for fair housing while openly selling to all.

Not to give away too much of the story but, at one point, according to Williams, Joe Eichler suggested he would build an entire tract – just for black people.

(One of Joe’s early mentors, Earl ‘Flat Top’ Smith, had done just that in Richmond a few years earlier.)

|

|

|

By 1954 Eichler was selling to black families in Greenmeadow, then other tracts. Eichler Homes never publicized this. The company did not buy ads in the black press, for example.

When white buyers complained about Eichler selling to a black Air Force officer in Marin County, Ned recalled, ‘‘In a rather severe tone, my father told these people that he was damned if they were going to tell him what to do.’’

“We were not identified as being builders who were trying to solve the race problem first and build houses second. We always were and even now, are identified as builders who happen also to follow this policy,’’ Ned stated in 1964.

Ned, whose career outside of Eichler Homes was varied, comes across as a visionary in this telling. Ned said he was ‘‘convinced that the race question is the single biggest block to advancement in this society.’’

“So I think that the builders cannot evade the fact that what they do is going to have an impact on the whole community, even on the nation, for a long time, and that they cannot simply say, ‘Well, I’m just a businessman, I’m here to make a buck.’ They are businessmen in a business to make money,” Ned stated, “and that is what they have to do, but they are also contributing to the kinds of communities in which people are going to live.”

- ‹ previous

- 624 of 677

- next ›