Beyond Flash and Fantasy

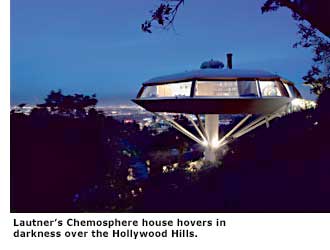

In a house designed by Southern California architect John Lautner, an entire wall may swing open on hinges to let in the view. Roofs sweep up, then down, in freeform fashion. His flying saucer-like Chemosphere house seems to hover in the Hollywood Hills. In a Lautner house, you'll rarely enter a rectangular room. "I love lakes and mountains," he once said, "and none of them are square."

In a house designed by Southern California architect John Lautner, an entire wall may swing open on hinges to let in the view. Roofs sweep up, then down, in freeform fashion. His flying saucer-like Chemosphere house seems to hover in the Hollywood Hills. In a Lautner house, you'll rarely enter a rectangular room. "I love lakes and mountains," he once said, "and none of them are square."

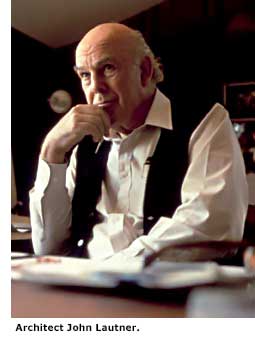

No wonder there are legends about Lautner (1911-1994), and how unfortunate. "He became famous for all the wrong reasons," Nicholas Olsberg writes in 'Between Earth and Heaven: The Architecture of John Lautner.' The book, which Olsberg edited, accompanied a recent exhibition of the same name at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles. Both were designed to bring Lautner his due.

Although Lautner won praise in the architectural and popular press right after World War II for innovative Los Angeles homes that were seen as models for the future, his work was later attacked as flash and fantasy, and Lautner himself regarded as an egotistical crank.

It didn't help that Lautner took offense, scorned the architectural press, and delivered jeremiads about the city where he lived and worked. "...when I came down here and drove down Santa Monica Boulevard, it was so goddamn ugly I was physically sick for about a year," he told oral historian Maggie Valentine, who interviewed him in 1994 for the Frank Lloyd Wright Design Heritage Project of the Frank Lloyd Wright Oral History Program at UCLA. He also disdained the people he had to work with in Los Angeles. "All they care about is money," he groused to Valentine. "Speculation. Dirty, cheating bastards, that's what they are."

And this is from the man whose swooping, 1949 glass-and-steel design for Googie's coffee shop helped shape Los Angeles' greatest gift to roadside commercial architecture in America, and gave the style its name.

Lautner often used the word 'real' to mean architecture that was authentic, creative, new—yet tied to ancient and timeless ways of building; based on the needs—including emotional needs—of his clients, and the demands of the site.

To Lautner, 'real' meant the opposite of everything he thought Los Angeles stood for—shallow, shoddy, and designed for quick sale. "People say 'why don't you move?'" he told Marlene L. Laskey in 1982 for 'Responsibility, Infinity, Nature,' for the Oral History Program of the University of California, Los Angeles. "But I don't know where to go because it's affecting the entire world."

"A whole, legitimate piece of architecture is a whole idea and a valid idea and a new idea for every situation," Lautner told Laskey. "It's not just following a style or a fad..."

Lautner was a structural pioneer, working with engineers like Edgardo Contini and T.Y. Lin to design truss-roofed homes, mushroom-like homes (like the Chemosphere), and thin-shelled, biomorphic homes of reinforced concrete.

Lautner, who sometimes spent days on a site before deriving the governing idea that would rule the house from general plan to each detail, once called himself "part psychiatrist, part metaphysician."

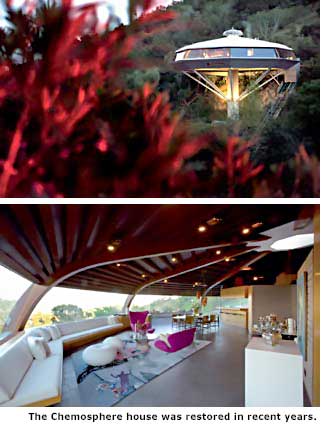

The Chemosphere house (the name came from a chemical company that donated sealants in exchange for free publicity), Lautner called "sensible," not "sensational." He saw the Chemosphere as a prototype for prefabricated middle class housing. He even drew up plans for a hillside filled with Chemospheres—one of several times in his 60-plus-year career that saw him designing housing tracts that never got built. Another, Alto Capistrano, planned for a community of 10,000 people near San Juan Capistrano, included pools, parks, light industry, apartments and townhouses, and cliff-side homes reached via 'hill elevators.'

"I think his greatest frustration was he got to build individual works within the landscape when he wanted, like Wright, to transform the whole space," Olsberg said.

Lautner's houses have proven to be practical and comfortable. "It's actually pretty easy to live in," said Mark Haddawy, who lives in Lautner's Harpel house. Haddawy had previously lived in a Pierre Koenig home that pleased neither him nor his pet. "My cat kept trying to escape," he said, adding, "From the moment we've gotten here, she's never once tried to bolt."

The Harpel house, from 1956, is a single-story pavilion, its freeform roof supported by concrete columns both inside the house and out, where the roof continues as a trellis. The house sits just below the Chemosphere, whose original owner, engineer Leonard Malin, decided to hire Lautner after watching the Harpel house being built.