The 'Life' House

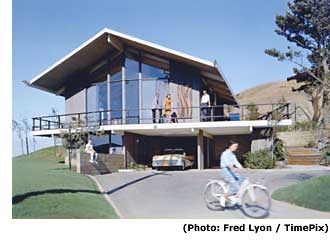

Two blocks away from the celebrated X-100 steel Eichler, in the San Mateo Highlands, stands another special custom-built Eichler house—one that has been a well-kept secret for the past 40-plus years. Unlike any of the Highlands' Eichlers that preceded it, this one was built on four levels, against a hillside, and was a commissioned prototype designed by a gifted architect outside of Eichler Homes' usual stable.

Commonly referred to as the 'Life' house, this Eichler showpiece was launched by a phone call—in fact, from the offices of 'Life Magazine'-- in September 1957. Pietro Belluschi, Dean of Architecture and Urban Planning at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, one of the top architecture schools in the country, was at the other end of that call. 'Life' wanted to know if Belluschi would be interested in designing a model house suitable for mass production as part of a series of articles 'Life' had underway on American housing.

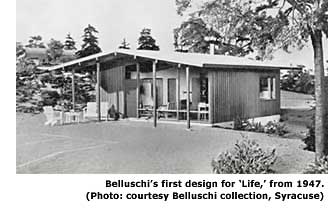

One of the most-renowned and successful architects on the West Coast, Belluschi had designed a model house for 'Life' a decade earlier, when he was still a practicing architect in Portland, Oregon. What 'Life' was looking for back then, in 1947—when the country was still recovering from a backlog in the building industry slowed first by the depression, then by the war—was a prototype for a low-cost, expandable house. 'Life' wanted a house that could minimally be built for no more than $4,000, the maximum the publication figured the average 28-year-old returning veteran with a wife and small child could afford.

Belluschi was known not only for his supremely elegant, simple, modern, beautifully designed churches and houses typically of wood, but also for his ability to remain within limited budgets. The original house he designed for 'Life,' featured in the April 28, 1947 issue, consisted of a welcoming but unpretentious low-pitched roof structure, with deeply overhanging eaves sheltering a broad terrace; and an open plan, with living, dining, and kitchen area basically one, and a master bedroom and child's room off to a side.

Belluschi's prototype was a startling success, generating a flood of letters from around the country requesting plans. A decade later, when 'Life' again tapped Belluschi for the design of a livable but affordable prototypical house, he had moved beyond residential work, and as dean at MIT was engaged in the design and planning of larger-scale structures, among them a new modern library for Bennington College; a $75-million commercial complex in Boston; Lincoln Center (for which he designed the Juilliard School of Music); as well as Grand Central City, or what was ultimately to become the Pan Am Building, in New York City.

Belluschi's prototype was a startling success, generating a flood of letters from around the country requesting plans. A decade later, when 'Life' again tapped Belluschi for the design of a livable but affordable prototypical house, he had moved beyond residential work, and as dean at MIT was engaged in the design and planning of larger-scale structures, among them a new modern library for Bennington College; a $75-million commercial complex in Boston; Lincoln Center (for which he designed the Juilliard School of Music); as well as Grand Central City, or what was ultimately to become the Pan Am Building, in New York City.

For the 1958 'Life' house, which again had a strictly limited, albeit substantially larger, $25,000 budget, Belluschi returned to the concept of the minimal house—basically rectangular in plan (though now with lofty ceilings and an angled prow on either end), low-pitched sheltering roof, deep eaves over broad terraces, and an open plan, with living, dining, and kitchen clustered together at one end facing the street, bedrooms behind looking out over the view. 'Life' had requested a split-level house on a sloped site generic enough in design to be built in all parts of the country with minor alterations to meet conditions of extreme heat or snow. To meet these requirements as well as remain within what he recognized as a severely limited budget for the kind of house 'Life' wanted, Belluschi doubled the square footage of the house and split it into four levels, staggering them so each made contact with the sloped ground.

One entered the house from the upward slope of the hill, several steps up from the carport, into an entry hall that led into the living area, with a door to the kitchen for deliveries off to the side. The master bedroom, with its own deck, was on the next tier up, visible from and opening onto the living space below, with bath and dressing rooms off to the side. Downstairs were the children's bedrooms and bath, and below them, again with the spaces staggered, were a family or 'all-purpose' room and the carport. The cedar-shingled roof and weathered redwood siding on the exterior were complemented by the cork floors and exposed wooden beams on the interior. Simple, practical, and efficient both in terms of space and materials, yet remarkably light and spacious, the 'Life' house exemplified Belluschi's handling of materials and planning skills at their best.