Once Upon a Dream

|

|

|

|

|

|

It was a dream of a job for a young man who was very much a dreamer. It's not every day, after all, that an architect with utopian visions is hired to design a utopia.

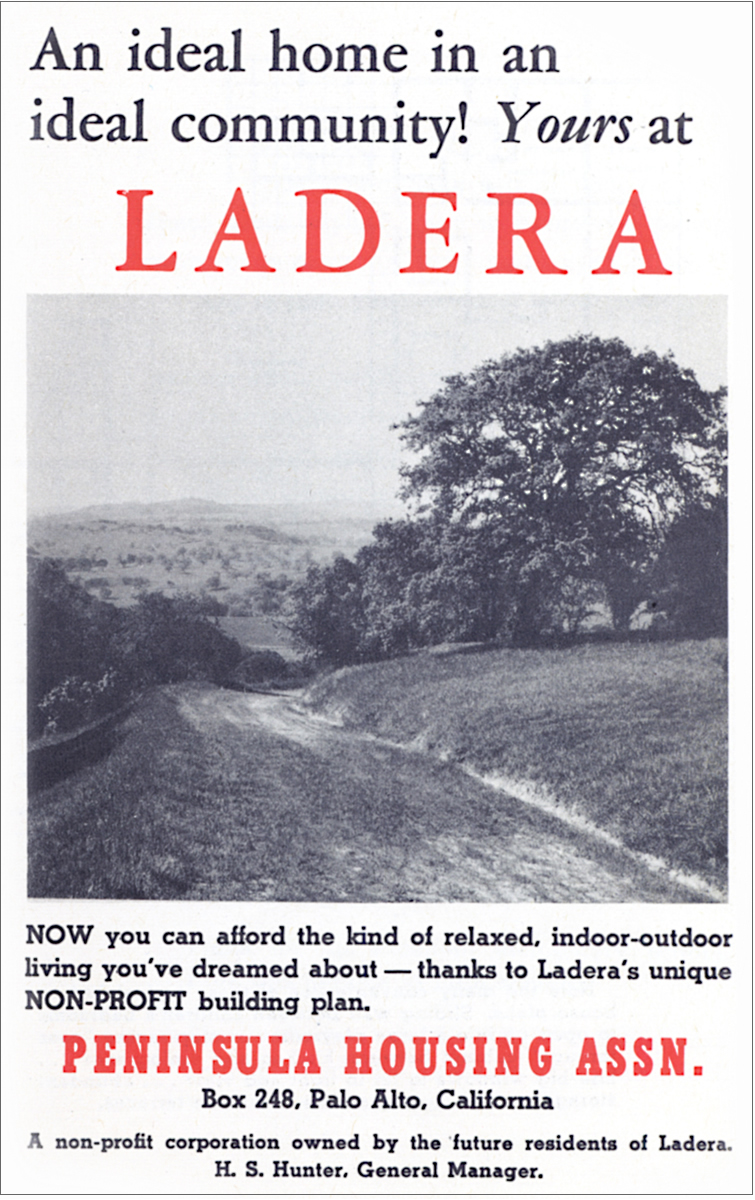

But that's what happened in 1944 when the 32-year-old Joseph Allen Stein was hired to help design Ladera, a 400-home cooperative housing tract in the hills west of Palo Alto. His teammates were Berkeley architect John Funk and landscape architect Garrett Eckbo.

More than just another postwar tract, Ladera would foster a form of communal living, with residents owning some land in common as well as stores, medical offices, and other services.

On top of that, it would be racially integrated. It's not surprising that the more liberal among the members of the Peninsula Housing Association, the co-op behind Ladera, were known by insiders as 'the dreamers.'

Some other members, fearing that integration would doom their venture, proposed either banning minority members or restricting their numbers. These were called 'the practical men.'

Stein, who went on to lead a career that took him to the other side of the globe, in some ways exemplifies mid-century modern architecture in California.

His designs are well thought-out, spare, filled with light, and beautiful. His politics was left of center and his beliefs deeply held—and acted on.

His focus, like that of many of his socially conscious colleagues, was on livable communities filled with affordable housing—but not of the Levittown sort that would soon start rolling across America.

"The home for the average American family must be brought down to the price level of the automobile," Stein wrote a few years before starting work on Ladera, "yet it should be more than a mere gadget; it must be a witness to man's humble spirit of romanticism as well as to his proud insistence upon up-to-date rationality and mechanical perfection; it must harbor the imponderable longings of his soul as well as serve the measurable needs of his body."

In a real utopia, after finishing up Ladera, Joe Stein would have gone to work for someone like, say Joe Eichler. Indeed, the architects who did design for Eichler—Anshen and Allen, Jones & Emmons, and Claude Oakland—shared Stein's commitment to low-cost housing and planned communities.

But Stein's career took a turn right about the time Eichler's homebuilding career began to flourish. And maybe Stein was just too much of a dreamer for Eichler. Stein's real interest was less in the middle-class homes Eichler was building than in 'social housing,' public housing or low-cost housing for workers.

Eichler did move into a light form of social housing in the early 1960s, when he developed two cooperative townhouse and apartment complexes in Santa Clara. (One became apartments after it failed and was taken over by the federal Housing Administration.)

Eichler also developed Laguna Heights, a low-rise cooperative, in San Francisco's Western Addition redevelopment area, and built an apartment tower and townhouses in the city's low income Visitacion Valley.