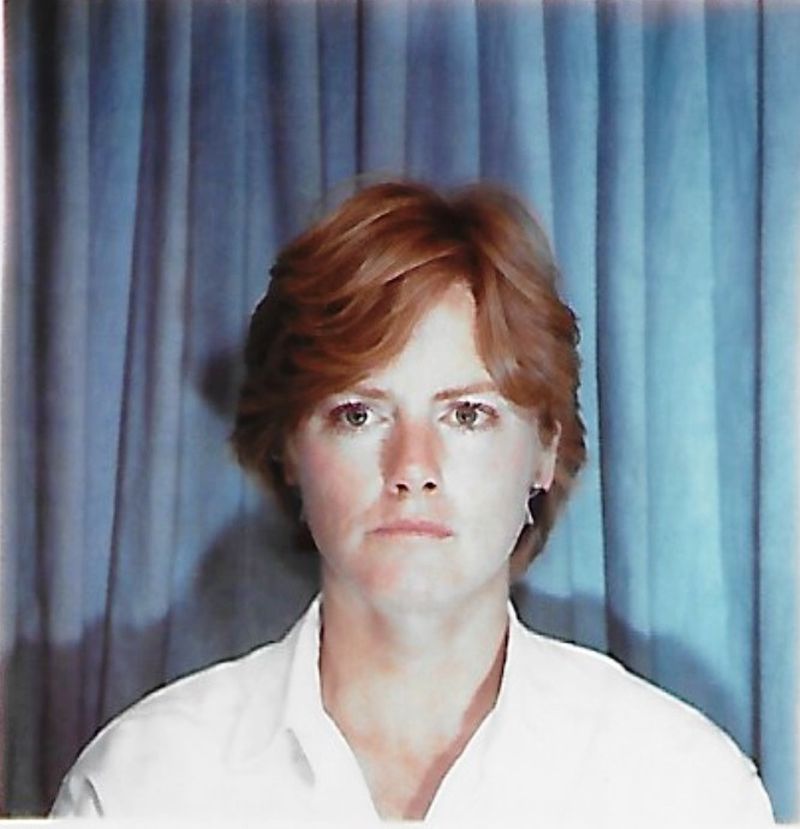

Pioneering Scholar Researched Joe Eichler

|

|

|

It was 1978, four years after Joe Eichler had died, and Eichler homes were far from the talk of the town. The excitement had died, and the homes were too new to be historic.

But a young graduate student in Virginia remembered the pull that Eichler neighborhoods had exerted on her when she was growing up in a standard tract home near the Eichlers in Palo Alto.

Casting around for a topic for her master’s thesis in architectural history, Susan Hall Harrison chose 'Post World War II Tract Houses: The Subdivision Developments of Joseph L. Eichler 1949-1956.'

Her 1980 thesis, which can be found at the library of the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, is almost certainly the earliest academic tome on Joe Eichler and his homes. It remains a valuable read today, providing a clear outline of the early days of his homebuilding.

(The thesis can now, as of February 2020, also be found at the Palo Alto Historical Association archive at Cubberley Community Center, 4000 Middlefield Road, room K-7, Palo Alto, where the thesis is available for reading. It cannot be checked out. Hours are Tuesdays 4 to 8 p.m and Thursdays 1-5 p.m. Thanks to Susan for donating her copy!)

The 100-page-plus thesis, plus many pages of illustrations, places the homes in context, makes clear how early homes evolved, and made use of sources no longer available to modern scholars.

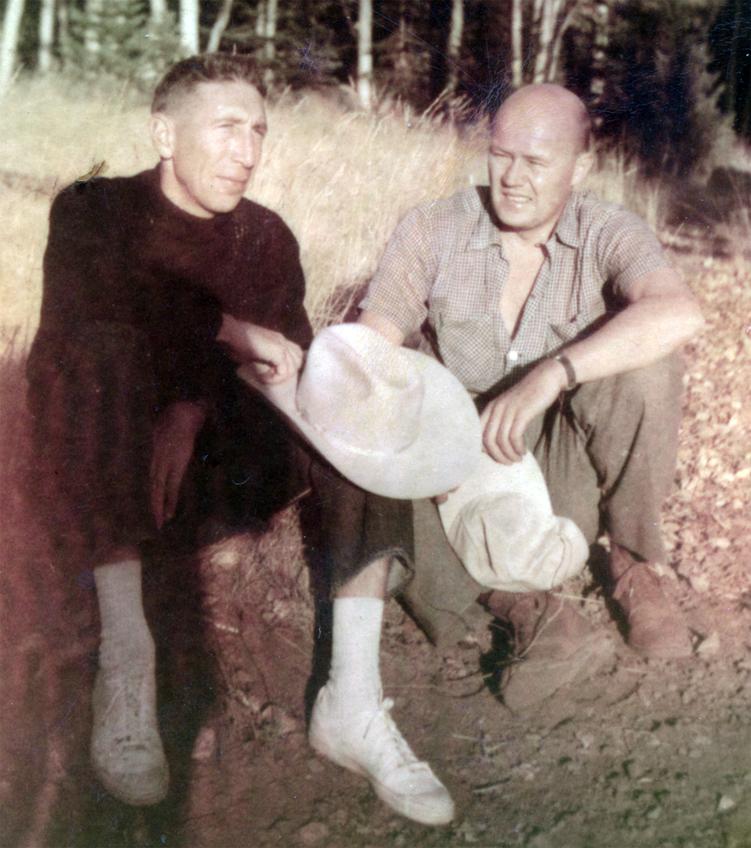

She interviewed architect Steve Allen, who designed the first architect-designed Eichlers with partner Bob Anshen. (Bob had died in 1964.) Steve died in 1992.

|

|

|

She also interviewed architect Claude Oakland, who died in 1989; Joe’s son, Ned, who died in 2014; Kathryn Imlay Stedman, a landscape architect who worked for Eichler, who died in 1997; engineers who worked for Eichler; photographer Ernie Braun, who died in 2010; and Elaine Sewell Jones, the wife of Eichler architect A. Quincy Jones, who also died in 2010.

But she didn’t get to speak to A. Q. Jones.

“I was sort of shy and hesitant about contacting A. Quincy Jones,” Harrison says, speaking from her home in Bridgehampton, Long Island. “I held back on that. Unfortunately , I held back too long, and by the time I contacted Elaine, she said he had died three weeks before.”

For anyone interested in the minutiae of Eichler history, Harrison's thesis has great tidbits. It’s well known that when Eichler won a prize for subdivision of the year and Jones & Emmons won the prize for best builders’ house of the year, Joe decided they should get together.

But rather than contact Jones & Emmons on his own, Joe dispatched Anshen and Allen to Los Angeles to assess the architects and their works. It’s a sign of how much faith Joe had in Bob and Steve – and how Bob and Steve showed no reluctance to share the Eichler account with another firm.

|

|

|

Harrison focuses on the value Eichler brought to the modernist quest to remake the American landscape.

She writes: “Statistics ... made it clear that if proponents of modern architecture were to significantly alter the living habits of the public at large, they would be compelled to collaborate with speculative or merchant builders. From the mid-1930s to the late 1940s the percentage of new housing stock produced by the merchant builder industry rose from 50 to 80 percent.”

No other merchant builder constructed more modern homes than Joe.

Harrison had mixed success with her interview subjects. Steve Allen, interviewed in his Sausalito home, where he lived with a poodle, she found “elderly, and he wasn’t very forthcoming with much information.”

Claude Oakland, who took over the Eichler account from Anshen and Allen, “was very sweet, very kind, very, very forthcoming and easy to engage with.”

But her favorite was Elaine Jones, who dedicated her time after her husband’s death to organizing his immense archive and promoting his work to historians. They became friends.

“She was fantastic,” Harrison said. “She and [designer] Ray Eames had both just lost their husbands. They were going to Carmel to spend Christmas together. My parents lived at Pebble Beach, and we had them over for drinks.”

|

|

|

Steve Allen did read over a draft of her thesis and made comments (and drew occasional exclamation points) on the pages.

Allen drew a bracket around a paragraph about efforts to encourage developers to hire architects for tract homes in 1950 – a rare thing to do at the time – and drew an exclamation point alongside.

Harrison interviewed people who lived in Eichlers, knocking on doors and talking to folks who were in their yards.

Did she detect that Eichlers had fallen from fashion? No.

“The few people I interviewed in Eichler houses were older people who had lived in them for years, and they just adored them,” Harrison says. “They had modernist furniture in them. And the other people were the architects who had been involved, and the engineers who had been involved, so they were interested.”

|

|

|

As a girl, Harrison’s interest in Eichlers was sparked less by design than by people. “I was intrigued because the people who lived in them were more interesting [than others], either professors at Stanford or psychiatrists, that sort of thing,” she said. “There seemed to be a different intellectual and cultural community in the Eichlers.”

As a professional architectural historian, Harrison went on to work for the Department of the Interior in Washington, answering questions from Congress people, federal staffers, and the public about National Register issues. Later she worked for the General Services Administration commissioning new art for courthouses and other public buildings.

Harrison is not surprised that Eichlers have retained and, in many cases, regained their appeal.

“I think Eichler homes are well suited to the climate and life in California, and that’s an enduring trait,” she said. “Modernist houses of the same period, say in Virginia and Maryland, haven’t physically fared as well, given the vast seasonal fluctuations in temperature and humidity.”

“More importantly for me, I think individuals, whether or not they are interested in design or aesthetics, recognize intuitively the benefits of having homes designed by architects -- the importance of volume over square footage, the advantage of having spaces that can function differently as children age and move away, etc.”

- ‹ previous

- 460 of 677

- next ›