Was Olsen NorCal’s Coolest Modernist?

|

Would you like to step back in time to the days when what we call mid-century modern was just getting started and nobody knew how it would turn out?

Stop by the library at UC Berkeley’s College of Environmental Design anytime by May 16 to enjoy a small but enlightening exhibit displayed in large glass cases, 'The Legacy of Donald Olsen: Modern Master.'

(Due to coronavirus, the library and the entire university are temporarily closed. The exhibition has been digitized so it can be enjoyed online.)

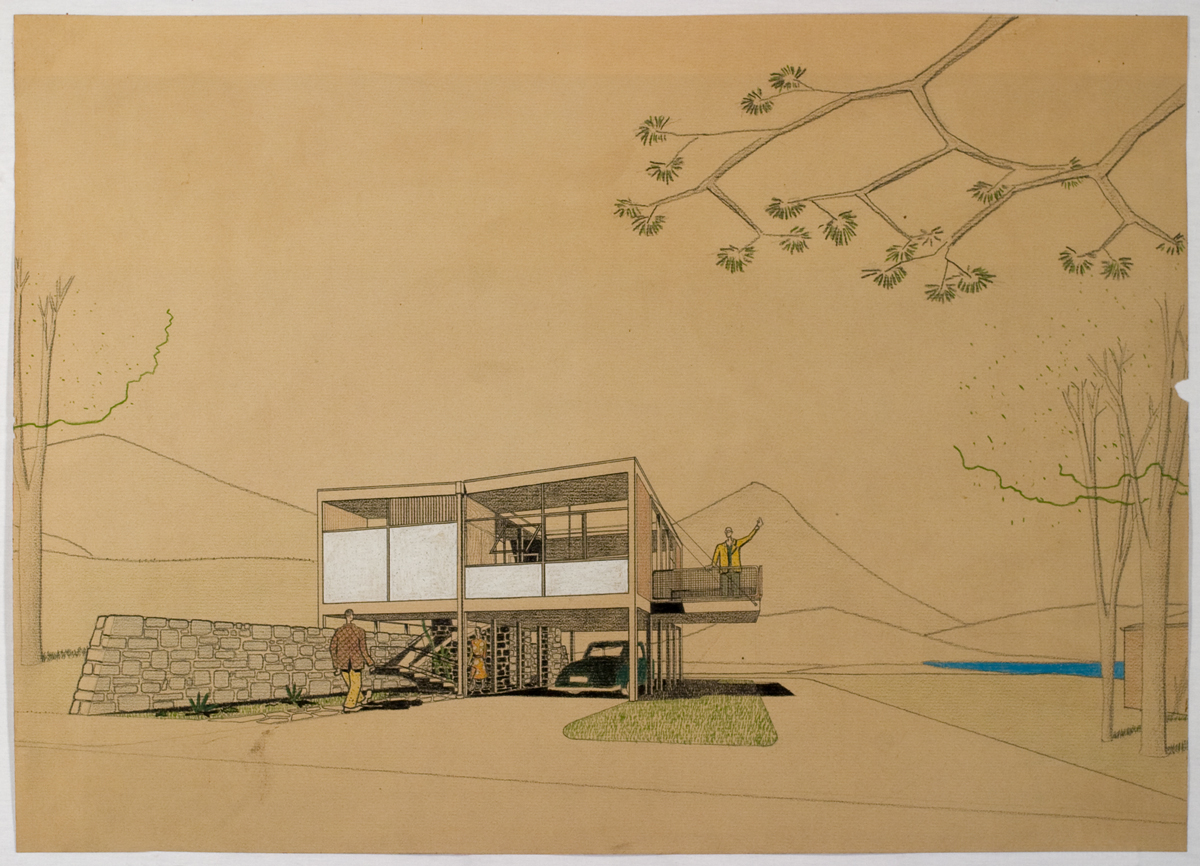

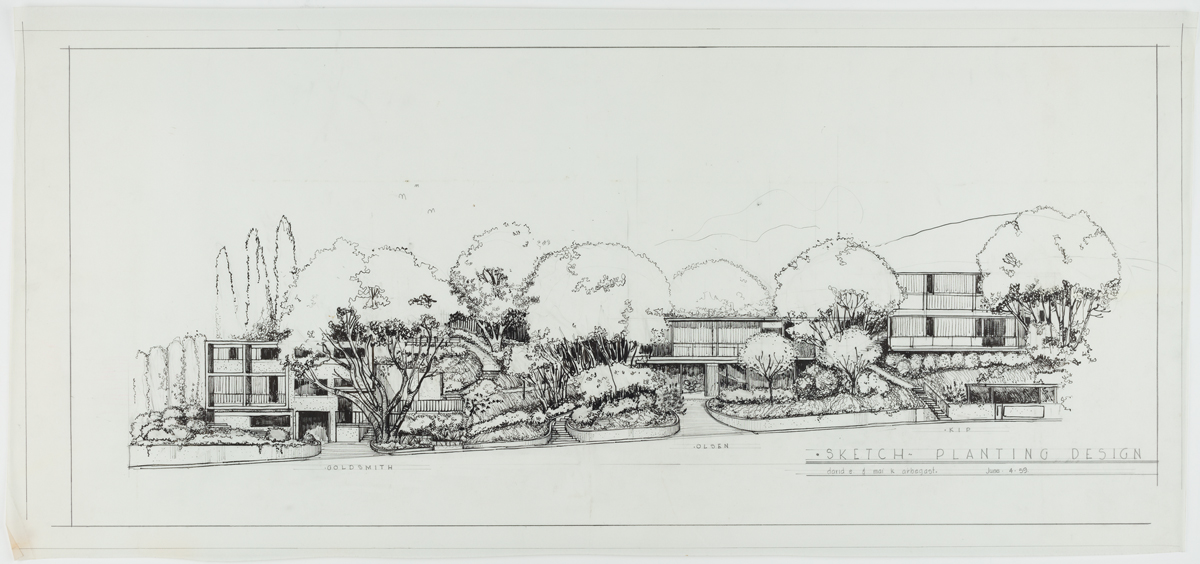

Imagine a landscape dotted with elegant, white-walled and witty homes; some lifted on pylons; many with nautical-like bridges, sporting bright red, blue, or yellow interior walls – just for accent, you know? And if there’s room, why not a spiral staircase descending one level, two, or three?

|

Olsen, FAIA, (1919-2015) was a rarity among Bay Area modernists of the post-World War II period – a dedicated International Style designer. While at the University of Minnesota he won a full scholarship to the graduate program of his choice. Olsen chose to study with one of the founders of that style, Walter Gropius, at Harvard.

But before he hit Harvard, World War II happened and Olsen chose instead to design dozens of buildings in and around Kaiser Shipyards in Richmond, where he met his future wife, Helen (Ohlson) Olsen, an artist, jeweler and fashion illustrator; and where the banging of metal produced a deep hearing loss that plagued Olsen's later years.

Olsen studied with Gropius after the war and maintained a long friendship.

When most Bay Area modernists clothed their buildings in natural wood and claimed fealty to the rustic tradition of Maybeck, Olsen proudly painted his wood white for a cool look. He didn’t think much of Maybeck except for one of his houses made not of wood but of reinforced concrete and looking not like a shingled cottage but like a villa in Pompeii.

|

Olsen, whose floating glass box of a Berkeley home is on the National Register and is on the market -- designed about 50 homes that range from quiet and compact to grand and dramatic. One large rambler of a place was cited as one of the 25 best houses in America in 1963.

Olsen also designed a number of speculative houses for ordinary people. Like many architects of the day, he took an interest in social housing.

Over the years Olsen designed stores, restaurant interiors, and other commercial and institutional projects, many never built. While running his own office he also served on the faculty of the College of Environmental Design for 36 years.

|

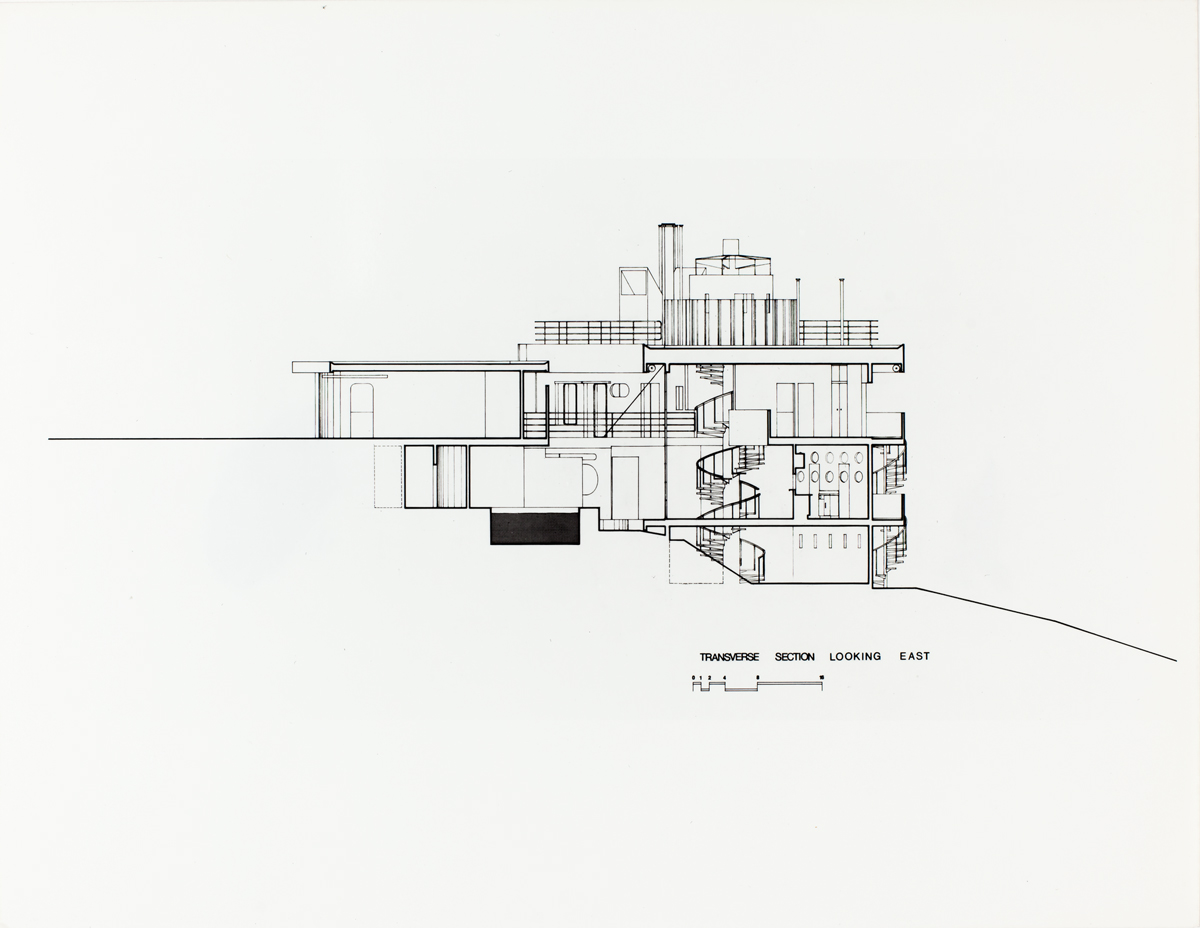

You’ll be seeing his largest structure if you visit the show. Wurster Hall, which houses the college and is named after its former dean, William Wurster, was designed by a team that included Olsen.

If you’re crazy about the place, or abhor it with fascination, you can listen to five hours of Olsen talking about its creation in an oral history recording.

Back in 2004 Olsen said that Wurster wanted a building that would encourage collegiality, with the library, staircase, and elevator meeting at a single spot.

“His theory was that you couldn’t help but meet people. You would simply meet, inadvertently,” Olsen said. “I predicted it ain’t realistic. Wurster either didn’t realize, or preferred not to realize, that people are every bit as good at missing each other as they are at meeting up with each other.”

|

“Anyone you don’t want to meet, you size up their habits and you notice when and where they come. You can easily not meet them. There were people that we never met. So much for the sociology involved with architecture.”

Katie Riddle, who curated the exhibit and is reference archivist at UC’s Environmental Design Archives, says the show originated because she had just completed the task of organizing and making available to the public Olsen’s archive.

“He saved every single piece of tracing paper, every drawing. They were all hand drawn. And he used so many different drawings of people,” she says.

“I’ve kind of fallen in love with his work. It was difficult to pick projects because I wanted to show everything. It’s been a real pleasure,”

|

Olsen worked for several leading architectural firms before forming his own small firm. He very briefly worked for Anshen and Allen, Joe Eichler’s first architects, right after the war, even though they didn’t share an aesthetic. (Steve Allen called the International Style “the enemy.”)

Among his projects for Anshen and Allen was a shopping center that was never built and a service station for Standard Oil.

“I made a sketch,” Olsen said in 2009. “I didn’t care for it, but it was a Standard Oil station. In the sketch I put a sort of jalopy getting gas, and the owner stepped out of the car and was smoking a cigarette.

|

“Oh, the man from Standard Oil came into the office, absolutely red. He said, ‘Mr. Olsen you know there is no smoking.’ He said. ‘And that car, we didn’t like that.’ I said, ‘Oh, are you against the common man?’”

“I said, this is just a rendering. This is just for you.”

When he was redoing the sketch, Olsen went on, “Bob [Anshen] came around and said, ‘We don’t want any of that International Style stuff around here.’ Well, that just fired me to go on. I did this big, elaborate station and had several people walking around the gas, all smoking cigarettes.”

“And the man from Standard Oil comes out again, ‘Mr. Olsen!’”

- ‹ previous

- 618 of 677

- next ›