Hello, Cool World: Painter, Karl Benjamin

Can 'cool' be codified? Beatniks with their bongos and bikers in leather would have said no. Wasn't cool akin to Zen—something indefinable, like smoke, a you-know-it-when-you've-got-it sort of thing?

Can 'cool' be codified? Beatniks with their bongos and bikers in leather would have said no. Wasn't cool akin to Zen—something indefinable, like smoke, a you-know-it-when-you've-got-it sort of thing?

But when curators put together an ambitious, innovative exhibit such as 'Birth of the Cool'—one that aims to show a connection, indeed, a shared zeitgeist, between certain architects, designers, jazz musicians, avant-garde moviemakers, and painters of mid-century California—definitions are forthcoming.

'Cool' meant art that, unlike the earth-shaking solos of bebop or the splatters of paint that seemed to burst from Jackson Pollock's very soul, was rational and restrained, but deeply emotional nonetheless. In "the ethos of cool," the show's curator Elizabeth Armstrong says, can be found "a cerebral mix of seeming detachment and effortlessness."

"There are the rationality and purity that are hallmarks of modernist design—a cool, some would say cold, aesthetic with hard edges, minimal forms, and an industrial sensibility," she writes in the stunning book-sized catalogue 'Birth of the Cool,' which accompanies the show of the same name. "And there is the cool of the hipster...an attitude that eludes those who try too hard to achieve it."

"Detached but smart," Lorraine Wild writes in her essay in the book, "imaginative but not overworked—can 'cool' be described in any other way?"

"To be cool," wrote LeRoi Jones, quoted in 'Birth,' "was, at its most accessible meaning, to be calm, even unimpressed by what horror the world might daily propose."

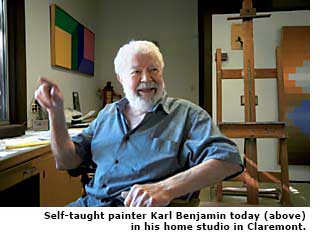

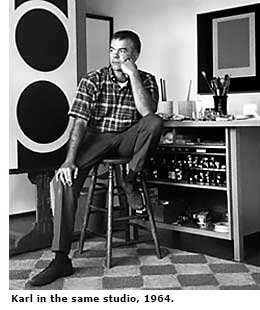

By any of these definitions, the painter Karl Benjamin, who never pounded drums nor rode a Harley, was cool—despite living in Claremont, a sedate college town 50 miles from the epicenter of Southern California cool, Venice Beach. Filled with artists and intellectuals associated with the town's colleges, Claremont had its own form of quiet cool.

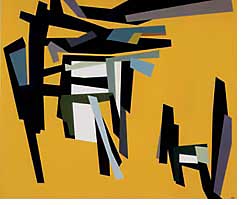

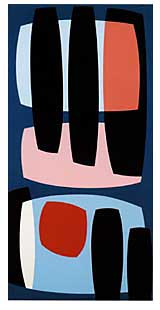

Self-taught as a painter, Benjamin developed a rigorously abstract style, with single-color shapes colliding, caressing or jumping about the canvas. His paintings can resemble mountains or Indian blankets, or appear systematic—though they are never about systems. Sometimes they suggest space, and other times the colors buzz like those in Op Art. But optical phenomenon is something else the paintings are not about. "Color," he has said, "is the subject matter of painting."

"Cool doesn't mean unemotional," Benjamin says. "It's understated. It's kind of an emotional expression where you're not burping all over yourself."

The curator Jules Langsner, who included Benjamin's work in the movement-defining 1959 show 'Four Abstract Classicists,' called one of his paintings "a series of percussive notes that would bring joy to the heart of a Gene Krupa." Benjamin is very much a jazz fan. "I think I wore out two copies of the 'Birth of the Cool,'" he says of the Miles Davis LP that gave the show its name.

Despite early acclaim, however, Benjamin never made a living from his paintings. Asked who bought them, he says: "Nobody." He then suffered the further indignity of being forgotten. When Southern California abstract painters began attracting national attention in the mid-1960s, that attention focused on the abstractions of Robert Irwin, Billy Al Bengston, and Larry Bell, and not on the earlier generation of abstractionists, including Benjamin, Lorser Feitelson, John McLaughlin, Frederick Hammersley, and Helen Lundeberg, whose works are highlighted in 'Birth of the Cool.' "What was to become the history," Benjamin says, "didn't include us."

Now, however, thanks in part to 'Birth of the Cool,' Benjamin and his generation are being rediscovered—just as the work of mid-century modern architects was rediscovered a decade ago.

For Benjamin, a soft-spoken man of 82, the attention is sweet. He's got a prominent gallery carrying his art, he's been profiled in the New York Times, and when the Claremont Museum of Art debuted, its inaugural show focused on Benjamin. And Benjamin's work is prominently featured in 'Birth'—including on the book's cover.