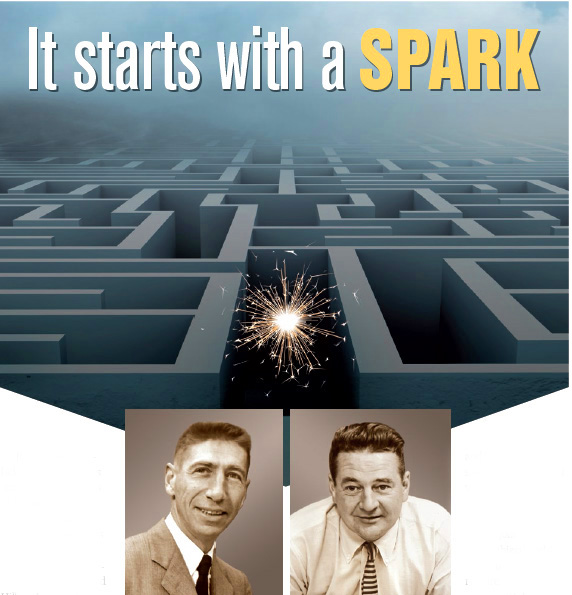

It Starts with a Spark

|

Do we owe the beauty and utility of the Eichler homes to the troubled childhoods of Joe Eichler’s architects Bob Anshen and A. Quincy Jones?

Did Jones’ near adoption by a Japanese family who owned a nursery influence his indoor-outdoor aesthetic or social concerns?

And what if anything does Anshen’s decision in his early 20s to quit a good job at a Wall Street bank—at the height of the Depression, when jobs were scarce—suggest about the arc of his architectural career?

And would Eichler Homes as we know it ever have come into existence if Anshen and his future partner in the firm Anshen and Allen, Steve Allen, had not run up an immense bar tab on their voyage to San Francisco as they completed their world tour in 1937?

To consider these questions, let’s turn to social science.

In late 1958 and early 1959 Anshen (1910-1964) and Jones (1913-1979) were among 40 of the nation’s top architects chosen to be feted, interrogated, tested, and observed like lab animals in an experiment at UC Berkeley, all to understand what makes creative people creative.

The events took place over four three-day weekends, ten architects each time. Anshen and Jones attended on different weekends.

|

“Both the art and science worlds had major stakes in creativity. Understanding its very nature could be the means of getting more of it out of humanity,” author Pierluigi Serraino wrote in The Creative Architect, his 2016 book about the Architect Assessment Project, headed by psychologist Donald W. MacKinnon of the university’s Institute of Personality Assessment and Research.

It’s not surprising Anshen and Jones were selected for the study.

Anshen had helped design an unusual church that suggests a cross growing from a mountain of red rock, a doughnut-shaped motel, and the Eichler atrium.

Jones’ designs included the Palm Springs Tennis Club, hundreds of aesthetically and structurally exciting custom and developer’s homes, and a planned community of cooperative homes at Crestwood Hills in Los Angeles.

The results of the architects’ creativity study received much press at the time but soon were forgotten. Serraino brought them to light studying the raw materials—interview transcripts, audio recordings, and questionnaires—at the archive of UC Berkeley’s Institute of Personality and Social Research, as the institute is known today.

|

|

|

Further attention is coming, with an exhibit organized by the American Institute of Architects in New York and the institute, tentatively set for 2021.

The material from the study is marvelous, not only providing insights into what makes an architect creative, but supplying previously unknown details about the lives of two of the principal designers of Eichler homes.

Bob Anshen went to work for Eichler in 1949, designing a home with partner Steve Allen for the Eichler family in Atherton. Anshen and Allen began designing Eichler’s tract homes that year also. In 1951 Jones & Emmons, which included Jones’ partner, Frederick Emmons, joined the Eichler team.

Until 1960, when Anshen and Allen lost the Eichler account, the two teams shared the role of designing Eichler homes, working independently of each other but sharing ideas. Innovations of one team—Anshen’s invention of the atrium, for instance—would be adopted by the other. Jones & Emmons continued working for Eichler until 1970.

What made Anshen and Jones creative? Let’s ask them.

What determines creativity in an architect, Mr. Anshen?

“If the spark isn’t there, if the philosophical content, if the proper materials and the proper expression aren’t used, it’s all wasted,” Anshen told the psychologist who interviewed him.