When Joe Eichler Spoke Out About Race

|

|

|

It was a momentous court decision, one that had homebuilders in the Bay Area and across the nation worried and angry. Another man who got angry was Joe Eichler, but he got that way for a different reason.

In the summer of 1958 a superior court judge in Sacramento – “a protégé of Chief Justice [of the U.S. Supreme Court] Earl Warren,” according to the magazine House and Home) “ruled flatly that builders and realtors may not discriminate against Negro buyers.”

The ruling was limited – to Sacramento County, and only to sales involving VA and FHA financing. But builders were afraid that similar rulings would come in other jurisdictions – thanks to suits brought, like the one in Sacramento, by the NAACP, or by similar civil rights groups. Also, VA and FHA financing was used in a majority of transactions.

|

|

|

“The decision – first of its kind – is already producing worries and repercussions among California builders,” the magazine, which was aimed at the trade, reported.

Among those worrying were leaders of the San Francisco branch of the National Association of Home Builders, the top trade organization. And among the repercussions were the reaction of Joe Eichler to those very worries.

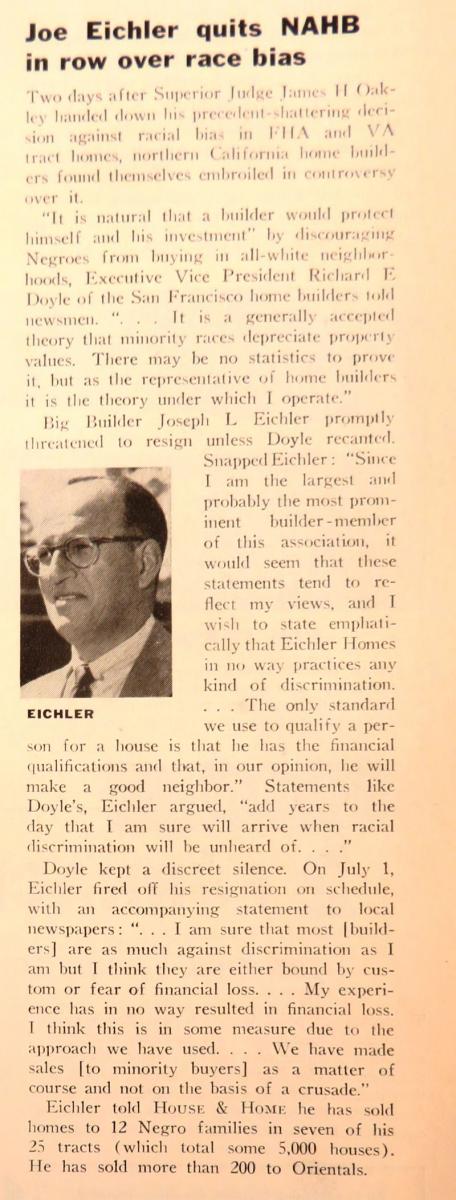

The San Francisco NAHB’s vice president, Richard F. Doyle, told the press the organization strongly opposed the ruling.

“It is a generally accepted theory that minority races depreciate property values. There may be no statistics to prove it, but as the representative of homebuilders, it is the theory under which I operate.”

But it wasn’t the theory Eichler had been operating under; he had sold his first home to an African American buyer at the start of the 1950s and was regularly selling homes to blacks and other minorities since at least 1954.

Unlike a handful of socially conscious homebuilders, whose small, homebuilding firms were as much social endeavors as profit-making businesses, though, Joe never made a big splash in the press about Eichler Homes' open housing policy.

Instead, he often worked behind the scenes to spread the word about fair housing.

But when the local housing organization to which he belonged took a public position in favor of discriminating against black home buyers, Joe could no longer keep silent.

First, Joe threatened to resign from the organization. Then, when the local NAHB refused to drop its opposition to anti-discrimination in housing, Joe did resign – while announcing his resignation in the press, sending letters to several Bay Area papers.

It made national news – in the pages of the magazine House and Home, and in other publications.

In his first missive to the NAHB, Joe wrote, “Since I am the largest and probably the most prominent builder-member of this association, it would seem that these statements [opposed to the court ruling] tend to reflect my views, and I wish to state emphatically that Eichler Homes in no way practices any kind of discrimination.”

Joe said that such statements opposed to open housing, “add years to the day that I am sure will arrive when racial discrimination will be unheard of.”

On July 1, when Joe resigned from the group, his letter to the press stated: “I am sure that most [builders] are as much against discrimination as I am, but I think they are either bound by custom or fear of financial loss.”

The magazine House and Home reported that Eichler Homes had, by that time, “sold homes to 12 Negro families…[and] more than 200 to Orientals.”

|

|

|

By not laying into other homebuilders as being racists or mean spirited, Joe managed not to burn fences.

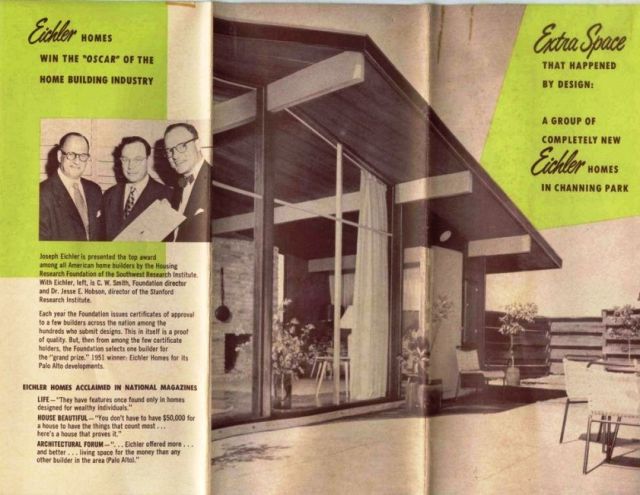

Just a year and a half later, at the start of 1960, Eichler and his two teams of architects – Jones & Emmons, and Anshen and Allen – were on the receiving end of some high praise from the national NAHB.

In association with the American Institute of Architects, the NAHB handed Eichler and his team an “award of honor for outstanding cooperation in the design and construction of merchant-built homes.”

“It is the first such award given to encourage the design and construction of the best communities and homes for the American people by promoting the collaboration between architects and builders,” the Associated Press reported.

The awards were handed out at an AIA convention in San Francisco and at the NAHB’s annual black-tie confab in Chicago.

- ‹ previous

- 634 of 677

- next ›