When Joe Eichler Bounced Back Big

|

|

|

It was a rough year for Joe Eichler, 1966. Eichler Homes was bleeding cash due in part to its ventures with urban projects in San Francisco. Perhaps due to the strain, Joe suffered a mild heart attack and was hospitalized.

When his son Ned arrived to straighten out the family firm, he later recalled, Joe seemed drained of all energy. “I had never seen him like this. He was flat.”

To save the firm Eichler sold controlling interest to two Southern California investors, remaining as board chairman. But they soon sued Eichler, claiming he had misrepresented the health of the company, among other things.

Out of Joe's hands, Eichler Homes, in fact, did go bankrupt two years later.

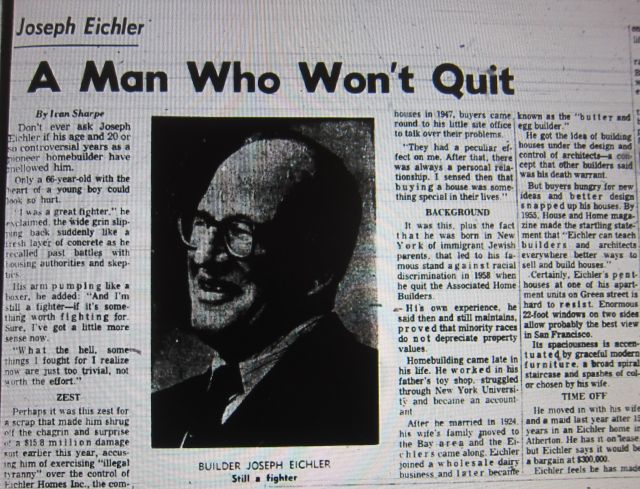

Yet, when Ivan Sharpe, a reporter for the San Francisco Chronicle, met with Joe at least twice towards the end of 1966, he found “a 66-year-old with the heart of a young boy,” a man who was willing to muse about his mistakes and talk about taking things slow – but was more intent on getting back to homebuilding.

He couldn’t call his new firm 'Eichler Homes' because the new owners of his former firm had the name. So one night, in bed in his penthouse at the Summit, a high-rise he’d developed atop Nob Hill, the name 'Nonpareil' came to him.

|

|

|

No, Joe, he was told. People can’t pronounce it, people can’t remember it. “But hell,” Joe said, “I’ve sold most of my houses to educated people.”

So Nonpareil Homes is what he called his new firm, also known as Joseph L. Eichler Associates. “It means without peers,” Joe explained.

“Now, at the age when most men would simply call it quits and relax in retirement, Eichler, who quite probably has won more prizes than any other builder in the country, is starting all over again,” Sharpe wrote.

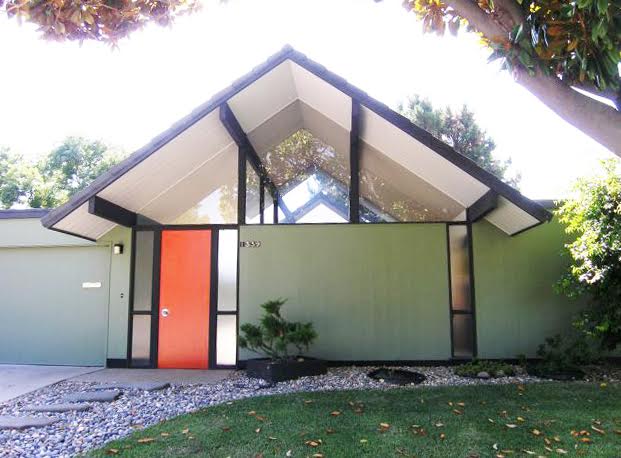

He interviewed Joe both at his new office, two freshly painted rooms in a seven-story office building built the year after the great Earthquake and Fire, and in the penthouse, with 22-foot-tall windows offering the best view in the city, Sharpe thought.

“Its spaciousness is accentuated by graceful, modern furniture,” he added, “a broad spiral staircase, and splashes of color chosen by his wife.”

At the builder’s office, Sharpe noted, “A receptionist smiled sweetly and tried to look busy.”

“Joseph Eichler looked positively gleeful across an uncluttered white desk that faced a row of shelves decorated with awards for home design,” the reporter went on, calling Eichler “remarkably spry looking,” and stating that he walked every day to the downtown office from his home high atop Russian Hill.

|

|

|

Ah, but did Joe walk back up the steep hill every evening? Maybe he did.

“I feel just the same as I did when I started at 46,” Joe told Sharpe. That’s how old he was when he began his homebuilding ventures.

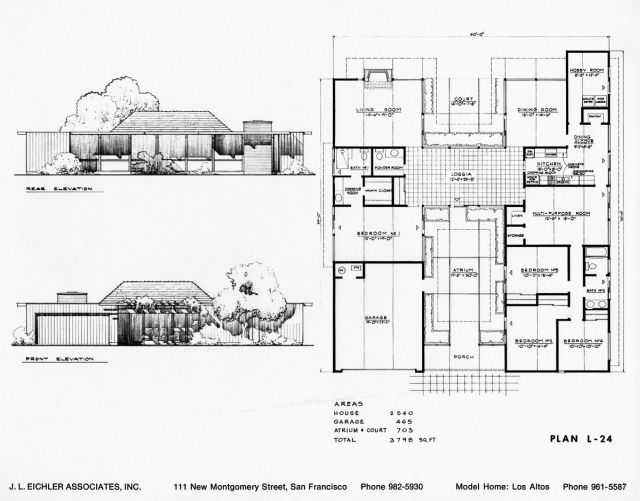

The first homes to be built as part of Nonpareil were aimed at a site in Sunnyvale, the city where, Sharpe wrote, Eichler had built his first architect-designed homes in 1949. There would be 47 new homes selling in the $35,000 range and designed by Claude Oakland.

“They are going to be entirely original, different than anything Eichler has built before,” Joe promised. The neighborhood was later dubbed Parmer Place, and is home today to about 43 Eichlers.

His new operation, he said, would be “moderate” in size, and indeed Eichler never reached the volume, or the size of staff, that he had maintained at Eichler Homes.

But in the interview he kept his options open for bigger things. “Of course you never can tell what might happen. If the opportunity were there…”

Why not retire, asked Sharpe, who probably suspected the answer.

“I enjoy working. Besides, I had to make a living. I wouldn’t say I was wealthy by any means. Just of moderate means.”

“If I wanted to live on a tight scale,” Joe said, “I could retire.”

|

|

|

How about mistakes, Mr. Eichler?

Yes, he had made a few.

“For instance, it was kind of silly to get into urban renewal projects, and I would avoid the multi-housing field again.” With this statement Joe was finally acknowledging that his son Ned, a former manager of the firm, had been correct in urging his dad to stick to single-family suburbia.

Also, oddly enough, Joe said he had made a mistake “in not regarding homebuilding as a purely money-making business,” in the paraphrased words of the reporter. Still, Eichler’s comments to Sharpe suggest that it was a mistake he would have made again.

From the start, Eichler said, in 1947, buyers would talk to him about their problems.

“They had a peculiar effect on me. After that, there was always a personal relation,” Joe said. “I sensed then that buying a house was something special in their lives.”

Sharpe went on: “It was this, plus the fact that he was born in New York of immigrant Jewish parents, that led to his famous stand against racial discrimination in 1958, when he quit the Associated Home Builders.”

|

|

|

And here’s another mistake Joe acknowledged that it seems he continued to make. Joe never did retire, but worked until his death in 1974. The homes he built in his later years are among the best-designed and most innovative of his career.

That mistake, he says, was working too hard. From now on, he said, he’d spend more time golfing, and would get more involved with politics. He had campaigned for Adlai Stevenson and Pierre Salinger and been much with the Democratic Party.

“Strangely too, for a land developer, he is passionately interested in conservation problems,” Sharpe wrote.

Though Ned, a self-avowed intellectual, has said that his dad never was an intellectual – well, maybe that was about to change.

“I have been giving some thought to doing some lecturing, maybe even writing,” Eichler said. “Would anyone be interested in a book of my life, do you think?”

- ‹ previous

- 632 of 677

- next ›