Architect Aaron Green

With its soaring, beamed cathedral ceiling topped by a skylight, the Mischel house of Palo Alto could be a church. It is, in fact, an Eichler home—but with a difference. Designed by architect Aaron Green in the early 1960s, the home is unique in the Eichler canon for several reasons.

With its soaring, beamed cathedral ceiling topped by a skylight, the Mischel house of Palo Alto could be a church. It is, in fact, an Eichler home—but with a difference. Designed by architect Aaron Green in the early 1960s, the home is unique in the Eichler canon for several reasons.

Most noticeable are the stylistic differences. Thanks to its shingled, pyramidal roof with-broadly projecting eaves—instead of Eichler's usual flat or gabled composition roofs—the Mischel house resembles a tent. The shingles provide a historically evocative, woodsy warmth and deliberate drama that contrasts with Eichler's usual straight lines and understated cool.

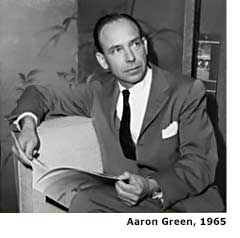

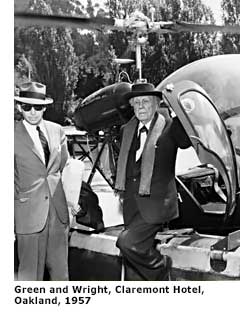

The Mischel home is also unique architecturally because it represents the closest Eichler ever came to working with his hero Frank Lloyd Wright. Green (1914-2001), a loyal Wrightian, ran the master's West Coast office from 1951 until Wright's death in 1959, overseeing such major Wright projects as the Marin Civic Center while also running his own practice. It was Wright's only branch office.

The home has a unique history that opens the door on a lost Eichler community—designed but never built—that would have been both startling and playful and stylistically unique in the Eichler canon. A 1961 site plan calls the neighborhood 'The Highlands' and shows 59 homes, but other documents indicate that up to 99 homes were planned. They would have been built on the northwest section of Eichler's San Mateo Highlands, which began construction in 1956.

The homes would have been built on Laurel Hill Drive and Court, Seneca Lane, and Westpoint Place. Eichler later filled some of these lots with homes designed by architect Claude Oakland. "They broke the mold a bit for Eichler work," says Jan Novie, president of Aaron G. Green Associates, Inc. "They got a little curvilinear." Novie worked with Green until his death.

The Mischel home was a prototype for one of three Highlands models and was dubbed the 'Sunspot,' for its skylight. Another model, the 'Arrow,' featured a V-plan with a powerfully diagonal gable roof that suggested a house about to shoot through the air. The third plan, the 'Semicircle,' would have been the only curvaceous house Eichler ever built. Its wall of floor-to-ceiling glass formed an ellipse, opening onto a deck. Architect Daniel Liebermann, who worked on the project at Green's office, calls this design "the frying pan."

The Mischel house appears to be the only home ever built using a design from this subdivision. It is not known why Green's designs were never built. It may have involved the cost of developing the hillside lots, construction costs associated with Green's plans, or both. How the project started is clearer.

Eichler, who'd had his modernist epiphany while living in Wright's Bazett house during World War II, had always wanted to work with Wright. Green did a later addition to the Bazett house. Legend has it Eichler approached Wright early on and was turned down. Liebermann's story is typical. Before contracting with Anshen and Allen at the start of his homebuilding career, Liebermann suggests, Eichler went to Wright and Green in their shared San Francisco office. "Probably they thumbed their noses at him," he says. "They didn't know Eichler. He was a spec builder."

What is for sure, however, is that Eichler approached Green in the late '50s or early '60s for site planning and design for the Highlands. Green was as Wrightian as you could get. "Everything I know about architecture I know from Frank Lloyd Wright. There is no question about it. That is my whole direction," Green told Tobias S. Guggenheimer, author of "A Taliesen Legacy: The Architecture Of Frank Lloyd Wright's Apprentices."

But like all of Wright's top followers, rather than copy Wright, Green incorporated Wright's principles of organic architecture into his own style. "Organic architecture has to do with relating to the immediate site, the client's program of needs, the climate in which the building exists, a natural and logical use of materials, whether structural or aesthetic," he told Guggenheimer. "It is a very direct, simple philosophy that I can't see how anyone could deny."

Green carved out a niche of his own, and was particularly known for environmentally sound designs that blend in well with the landscape. Green's designs were bolder than Wright's in expressing their underlying structure, using structural elements for rhythmic decoration.