It Takes Two - Page 5

7. KEN AND REGINA JONES

|

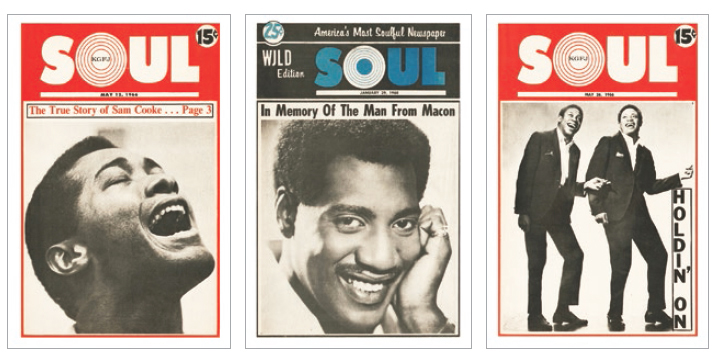

At its height—and it hit its height quickly—SOUL magazine was the Rolling Stone of Black popular culture, reviewing the music and visiting with James Brown (who wrote his own column), Stevie Wonder, Aretha, Pam Grier, Muhammad Ali, and many more.

The magazine didn't shy from controversy. 'The Men Behind the Music,' profiling record execs, "was intentionally a demonstration that there were really no Black people with power," Regina recalled in a 2012 interview for UCLA's Oral History Collection.

SOUL (1966-1982), which sold internationally, was birthed at the dining table of Regina (1942- ) and Ken Jones (1938-1993) after they'd witnessed the 1965 Watts Riots from their Los Angeles home. "It completely altered my life," Regina said of the riots.

"Ken's desire was…to help people by coming up with SOUL, to spread good news, and let Black people know there were Black things going on that were positive using the medium of entertainment to do it."

"In less than a year," the Los Angeles Sentinel wrote, "the newspaper spread like wildfire across 30 different cities in the country."

|

|

|

All this from a man with just a few years of community college behind him, who'd been working as a DJ and at a low-level job in TV news, and from a young woman who had the first of her and Ken's five children at 15.

But Regina had been an entrepreneur since childhood. And Ken was a compelling figure who rose quickly in TV news, becoming the first Black anchor in the city and a celebrity.

The couple complemented each other—Ken "the idea man," Regina said, and Regina overseeing the publication.

Regina's work was incessant, exhausting, and hard. SOUL lost ads to competitors along the way. And Regina and Ken eventually grew apart, separated, then divorced.

SOUL Publications, writes Susan Anderson, curator at the California African American Museum, "was a pivotal vehicle for shifting American culture from an era of 'race records' and Jim Crow movie theaters to becoming the locus of popular culture production, with Black cultural expression as its main impetus."

8. LOU HARRISON AND BILL COLVIG

|

|

|

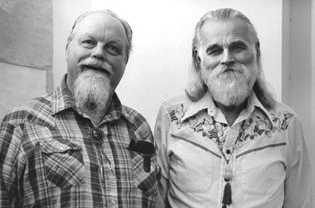

Sometimes the partner you need is the partner you find. That happened on a 1967 night at San Francisco's Old Spaghetti Factory restaurant-cabaret, where Lou Harrison, a noted composer for 30-plus years, was presenting a work.

In the audience was William Colvig, who had studied music but became an electrician instead as well as an environmentalist and Sierra Club hike leader.

From the start of his career Harrison, who grew up in the Bay Area, studied world music, blending Asian, Latin, and early European music into various blends of his own. He rejected the standard scales and sought new sounds.

As a student he spent much time in San Francisco's Chinatown. "By the time I was an adult," Harrison wrote, "I had heard much more Chinese opera than the Western variety."

He produced symphonies, chamber pieces, vocal works, and signature percussion pieces with a rhythmic pulse, often with beautiful soothing melodies, at times evoking Indonesian gamelan music.

|

Standard instruments often did not do justice to Harrison's music. In earlier years he and avant-garde composer John Cage built instruments by raiding junkyards for auto brakes and mattress springs.

Colvig was an explorer himself. He hitchhiked from San Francisco to Patagonia, climbing mountains in Peru and Chile along the way.

At the Old Spaghetti Factory Harrison and Colvig discovered their shared interests, including membership in the Society for Individual Rights, a gay rights group. Within weeks of meeting, they began a life together that would span 33 years, sharing Harrison's cabin in the Santa Cruz Mountains.

Colvig (1917-2000) and Harrison (1917-2003) built a complete American gamelan instrument ensemble for Harrison's compositions, and then built two more. Colvig made the gamelan of "aluminum tubes and slabs with can resonators and modified oxygen tanks suspended in wooden frames."

Colvig sometimes appeared onstage when Harrison performed with his gamelan. In public at least, Harrison seemed the dominant personality, with Colvig a quiet presence. Colvig deeply cared for the couple's cabin in the woods. "Sometimes he'd fall asleep during dinner parties," one friend said of Colvig. "But in the mountains he came alive."

Photography: Ernie Braun, Eric Golub; and courtesy Lothian Furey, Regina Jones, Office of Charles and Ray Eames, Studio Potter, Bonhams, Jess Collins Trust, Harrison and Colvig estates, Ackerman family estate, Rico Tee Archive